By Michael Roberts

The Great Recession of 2008-9 was a turning point for the US global strategy. Up to then, the general aim was to ‘engage’ important economic powers like Russia and China. Throughout the 1990s onwards, the US government pressed for the opening-up of their economies to multi-nationals and banks from the ‘West’.

These economies would then grow and trade, but in doing so also provide the global profits expansion that US imperialism needed as domestic profitability began to slip. ‘Globalisation’ would take advantage of cheap labour and new markets in China and the rest of the Global South which had expanded sharply from the early 1980s, under this policy of ‘engagement’. It was no accident that the World Bank published a report in 2013 calling on China to move quickly to a full ‘market economy’.

The best laid plans of US imperialism go awry

But the Great Recession changed all that. It became clear to the US strategists that, while globalisation brought extra profit, it also led to much faster economic expansion of countries like Russia, China and east Asia. The problem here was it was becoming clear that the likes of China and Russia (but particularly China) were not prepared to play ball with American imperialism and its multi-nationals. Russia sought to link up with Europe and separate it off from the UK and the US; while China sought to rival the US in technology and spread its influence throughout the global south. US capitalism plunged during the Great Recession and the advanced capitalist economies crawled along afterwards during the Long Depression of the 2010s. Meanwhile, China grew rapidly and Russia also built up it energy and mineral exports. This was too much. Something had to be done to put these rival economic powers in their place. ‘Engagement’ was dropped for ‘containment’.

Under the Trump administration, the US sought to isolate China with tariffs and bans on Chinese goods and companies. It insisted that Europe start paying for an expansion of NATO and arms in Europe. Under Biden, that policy was extended to back any pro-West and nationalist parties against Russia. The aim to was to include in NATO all countries along Russia’s borders, most of which were keen to take advantage of supposed economic prosperity from the European Union and ‘protection’ from Russian control with NATO. This has culminated in the Ukraine conflict.

The consequences for Ukraine

Ukraine is now being destroyed by Russian bombing and arms. Thousands have died, millions have been displaced and/or fled the country. The economic base of the country is being annihilated. Before the war, Ukraine was already a very poor country with a real GDP of just $160bn. Before this war is over – and it looks like lasting years, not weeks or months any more, that GDP is going to be halved at least.

Ukrainian sources estimate the cost of restoring infrastructure: financing the war effort (ammunition, weapons, etc.); losses of housing stock, commercial real estate, compensation for death and injury, resettlement costs, income support, etc.) and lost current and future income at from $500 billion to $1,000 billion. The World Bank estimates that Ukraine’s produced capital stock per capita in 2014 was approximately $25,000, which amounts to approximately $1.1 trillion at the aggregate level. Early reports by government officials and business leaders suggest that 30-50% of that capital stock has been destroyed or severely damaged. Assuming 40% destruction, the cost stands at $440 billion.

In addition, on the assumption of a cost of €10,000 per refugee (per year), the cost of financing 5 million refugees for one year is €50bn, or 0.35% EU GDP. So to restore the Ukraine economy and rebuild is likely to cost $500bn minimum, say over the next five years. That’s about 1.0% of EU GDP per year or 0.75% of G7 GDP – at a minimum.

Ukraine – the touchstone of US global containment policy

Will the West in its wisdom decide that it is worth spending that sort of money to fund Ukraine’s war effort indefinitely, supporting its population and rebuilding the country as a NATO bulwark against Russia? It looks like it. Ukraine is becoming the touchstone of the US global containment policy. Already US President Biden is pushing US Congress to agree to $30bn in support of Ukraine. But he is refusing to cancel or reduce student debt that has now reached $1.8trn. International policy is more important that helping American youth to get an education.

For example, here’s what Martin Sandbu, the Keynesian columnist in the FT, said: “the EU, which should shoulder the bulk of this (and support radical debt relief for Kyiv as with post-war Germany) should not see this as an expense. EU companies will be contracted for infrastructure, housebuilding, transport and more — but should transfer skills and technology to Ukrainians. Beyond this, it is an investment in Europe’s values and its security. It would bring 44mn people firmly inside the liberal democratic fold and into the social market economy — a historic achievement to rival the continent’s post-cold war reunification and the Marshall Plan itself.”

Prospects for a new ‘Marshall Plan’

the year before the Marshall Plan was signed.

By Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-B0527-0001-753 / CC-BY-SA 3.0, CC BY-SA 3.0 de

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5360200

Will the US and Europe go further and opt for what might be called a Marshall Plan for Ukraine? The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The initiative was named after United States Secretary of State George C. Marshall. The US transferred over $13 billion in economic recovery programs to Western European economies after the end of WW2. The aims was to rebuild war-torn regions, remove trade barriers for US mulit-nationals, modernize industry, improve European prosperity, and so prevent the spread of communism George Marshall’s stated goal in his 1947 speech was “to permit the emergence of political and social conditions in which free institutions can exist”.

How does the Marshall Plan compare with the cost of an aid plan for Ukraine? Well, $13bn in 1948 was about 1.1% of US GDP then and is equivalent to about $130bn now. So any Marshall Plan for Ukraine would have to deliver double that, as shared between the US and Europe. The 1948 plan was composed of both outright grants and loans. The aid accounted for about 3% of the combined GDP of the recipient countries between 1948 and 1951, which meant an increase in GDP growth of less than half a percent. Ukraine will need much more.

Opening up of markets revived capitalism after WW2

What really revived Europe’s capitalist economies from 1948 was not so much the Marshall Plan, but the opening-up of US and European markets to Europe’s industries, which could expand based on very cheap and plentiful labour after the war and the ability to purchase the latest technology. Is that the way forward for a weak and destroyed Ukraine? Only if Ukrainians can live on extremely low wages and expect little in the way of public services, while Ukraine’s capitalists (who used to be called ‘oligarchs’) and US and Europe’s multi-nationals take over Ukraine’s natural resource base.

But It seems that the US (and Europe more reluctantly) are prepared to stump up the cash to get Ukraine fully restored as a pro-West state in order to weaken Putin’s Russia. Most historians reckon that the political gains for capitalism after 1945 from the Marshall Plan were even more important than the direct economic ones. Europe was kept safe from Communism. Indeed, the CIA received 5% of the Marshall Plan funds (about $685 million spread over six years), which it used to finance secret operations abroad. Through the Office of Policy Coordination, money was directed toward support for pro-business labour unions, and anti-Communist newspapers, student groups, artists and intellectuals.

In an analysis of the Marshall Plan, Keynesians Bradford DeLong and Barry Eichengreen concluded that: “It was not large enough to have significantly accelerated recovery by financing investment, aiding the reconstruction of damaged infrastructure, or easing commodity bottlenecks. We argue, however, that the Marshall Plan did play a major role in setting the stage for post-World War II Western Europe’s rapid growth. The conditions attached to Marshall Plan aid pushed European political economy in a direction that left its post-World War II “mixed economies” with more “market” and less “controls” in the mix.

The cost to the West of the war in Ukraine

As for Ukraine, it is not the end of the cost for the West. The US is now insisting that Europe break with the use of Russian oil and gas. Phasing that out even as fast as the end of this year is going to cost Europe in higher energy prices and lower supply. That will take perhaps another 0.5% of GDP out of the European economy, which is already heading towards a recession. Inevitably that will force governments to expand their spending, both on weapons to meet new NATO commitments and on ‘butter’ as unemployment rises.

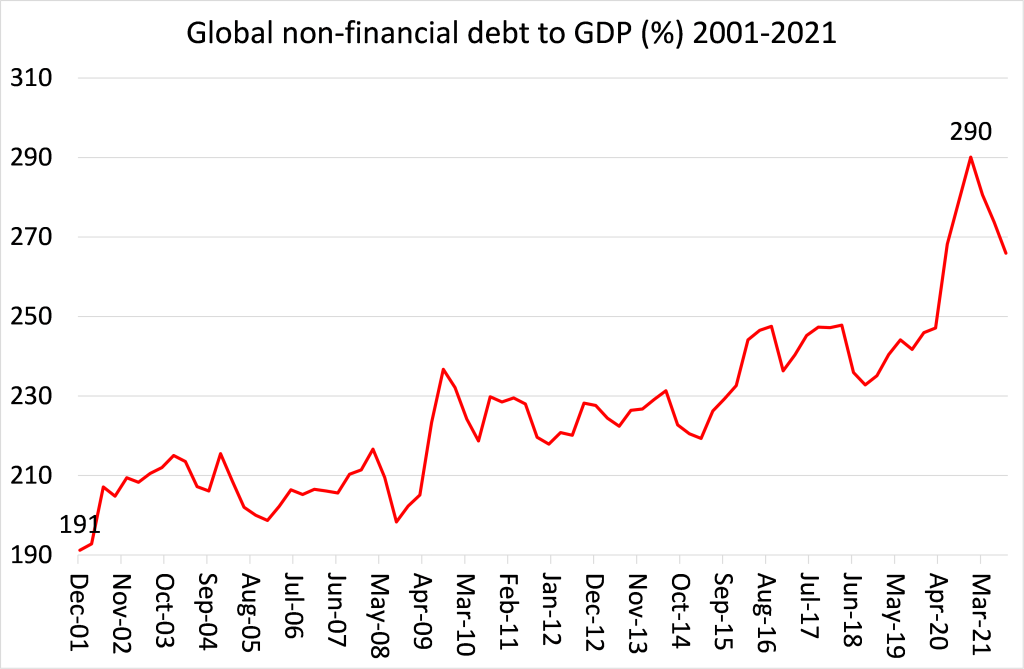

Again, this is at a time when government debt to GDP in most economies is at its highest since the Marshall Plan began. According to the IMF, global government debt to GDP stands at 97%, up 20% just from 2017 and is forecast still to be way higher in 2027 than in 2019 before the COVID pandemic hit. In the advanced capitalist economies, government debt to GDP was over 120% in 2020, with US gross debt at 134%. If you include private sector debt, then global debt reached 290% of GDP in 2021, up 40% from 2001. And the IMF forecast for 2027 does not take into account a Marshall Plan for Ukraine and the NATO build-up.

There is big price ahead for working people in the West to pay for saving Ukraine from Russian domination and opening up the country to Western multi-nationals. But it seems to the strategists of capital that it is a price worth paying by the working people of Europe and the US, with more costs to come in dealing with China over the rest of this decade.

Reparations would escalate confrontation with countries like China

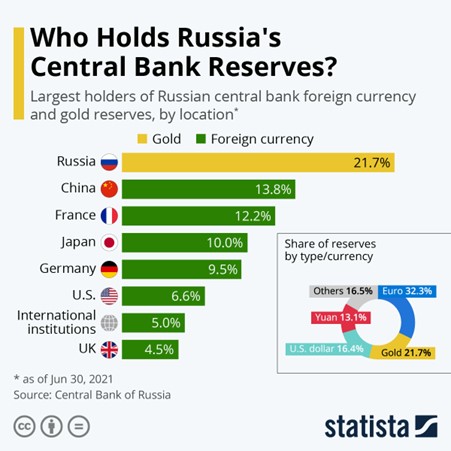

Of course, the burden of funding Ukraine could be reduced if the Western powers order the seizure of Russian foreign exchange (FX) reserves held abroad as reparations for Ukraine – that might be worth some $400bn. But then that would be another step up the ladder towards outright confrontation with resisting powers like China. No wonder this week Chinese leaders discussed how to protect their $3trn of FX reserves from seizure by the Western powers.

From the blog of Michael Roberts. The original, with all charts and hyperlinks, can be found here.