Reviewed by Steve Hadden, Warrington

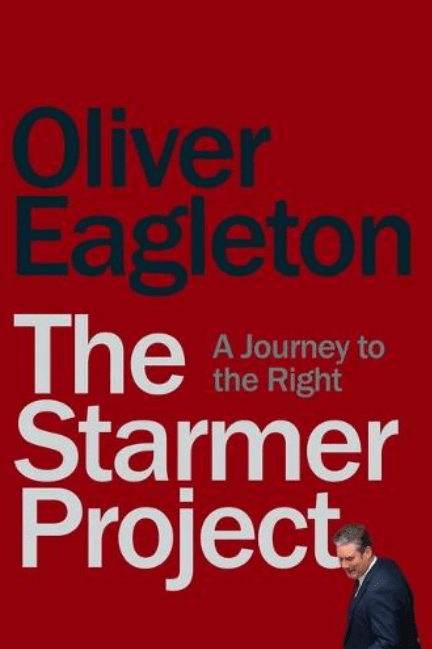

In his recently published memoir, Always Red, Len McCluskey asks “Who is Sir Keir Starmer? A babe in the woods, new to politics, fallen prey to his advisors? Or someone altogether more calculating, following a plan to marginalize the left?“. Oliver Eagleton’s much anticipated political biography now answers that question emphatically. It is 194 pages long and written in a language-rich style that is extremely readable without being florid or overly academic. The wealth of detail does not weigh down the narrative drive or astute analysis and observations that are made throughout the text.

Eagleton does not see Starmer as just a New Labour dupe or a successful and ambitious legal professional chancing his arm at a political career; rather he suggests, “We must rather uncover the more durable aspects of his thought-world and assess their relevance to the present conjecture”.

Excluding the introduction, the book has five principal sections: the Lawyer; the Politician; the Candidate; the Leader and finally the Aftermath. Here, I will discuss each section in turn, trying not to quote too much and just giving two or three examples of the subject matter and discussion points. I’ve read a few comments that suggest that Starmer’s time in the legal profession is perhaps the most telling part of the narrative and I tend to agree, so, this will be the part I will spend most time on.

On becoming DPP his attitude changed

I must admit I can’t ever remember hearing Starmer’s name until after the 2017 general election, although during the nomination meeting at my CLP in 2020, someone spoke in favour of nominating him, saying that they’d “followed his legal career with great interest”. I voted for Rebecca Long-Bailey, but given what has happened since he became leader, perhaps I should have been following his career too.

The Lawyer. Starmer was a specialist human rights lawyer, a fact skilfully exploited during his leadership campaign. He worked pro bono on several high-profile cases. Most famously, the so-called McLibel trial, which can safely be regarded as a success, insofar as it showed that a huge corporation was not ‘above the law’ and it was a mighty scalp for a relatively young lawyer to hang on his belt as far as his future reputation was concerned. It wouldn’t have seemed significant at the time, but as a member of the Haldane Society of socialist lawyers, some of his contemporaries recall him trying to de-politicize the organisation and guide it towards becoming an NGO, with emphasis on a ‘liberal’ defence of human rights.

However, on becoming the Director of Public Prosecutions, his attitude changed, or maybe revealed what had been part of his worldview all along. Of course, he was in a different role, but few vestiges of his work as a human rights lawyer seemed evident. This chapter of Eagleton’s book meticulously details the various cases he dealt with and how he very soon emerged as a dedicated servant of the state and a rigorous, often ruthless, enforcer of its will.

Starmer would have extradited Gary McKinnon to the USA

His role in the Julian Assange case is well known. He would have had Gary Mckinnon, the autistic computer expert who hacked into a US security computer in search of information aboutUFOs, extradited to the USA and was reportedlyfurious when he was overruled by Theresa May, then Home Secretary.

In fact, he developed his own ‘special relationship’ with the US Justice Department. “Starmer’s CPS agreed to act as proxy”, Eagleton writes, “using State Department funding to push through judicial reforms that complemented the war on terror”. Whether this is one of the roots of his unquestioning Atlanticism or just a reflection of it, is unclear, but it is all too evident now. As any one of those Labour MPs who signed the Stop the War petition will attest.

During the trials following the 2011 riots that were triggered by the Mark Duggan shooting, we can perhaps see something of the attitude and treatment meted out to left wing members of the Labour Party at present. The courts worked 24/7 to process defendants, many of them younger teenagers. He pushed for the charges to be changed from theft to burglary, which carries a higher sentence. He even visited one of the courts in the early hours to give the ‘troops’, the Crown Prosecution staff, a morale boost.

Is it an exaggeration to say that the Starmer we see now is acting entirely consistently with his tenure as Director of Public Prosecutions? Had more Labour Party members been aware of this when he stood for leader could he have been questioned more specifically about what he was actually about?

The Politician. I half consciously re-named this part ‘Karie Murphy sussed him and John McDonnell, oh dear’. [Murphy was Executive Director of the Leader of the Opposition’s Office under Jeremy Corbyn from 2016 to 2020 – Ed]. What this part of the book is especially good at, is narrating in detail how the Corbyn LOTO got ensnared in the Brexit issue and, political novice that he might have been, (think of the Len McCluskey’s quote at the top), we see Starmer’s deep and evolving role in it.

Well-connected people used him to undermine Corbyn

My flippant comment aside, this part does make for painful reading. Yes, Starmer didn’t have much of an idea on policy or ideology, yes there were well-connected people all too willing to utilise him to undermine Corbyn. But the way Starmer patiently ‘played’ the Brexit issue to destroy Corbyn showed a ruthless personal ambition and a capacity for endless Machiavellian manoeuvrings. All of this – and at the same time building a team and a platform for his own leadership bid. I must re-iterate that John McDonnell does not come out of this well.

The Candidate. His leadership bid was taking form as early as September 2019, it seems. I’m sure we all remember the video, featuring Doreen Lawrence, former striking miners, the Wapping picket line, which he attended as a student, much to the anger of David Miliband and Stephen Twigg. It seems at least those two have been consistent.

Starmer’s nearest rival, Rebecca Long-Bailey, was slow out of the blocks and couldn’t appeal to a battle-weary Labour membership. I would also refer potential readers of Eagleton’s book to Morgan McSweeney’s analysis of the Labour membership and how it fed into Starmer’s unity message.

As we now know, as a leadership candidate Starmer deliberately misled the membership and he did so on a grand scale. The New Labour mandarins had long chosen him as their candidate, the one who could overturn everything that had ‘gone wrong’ since 2010, let alone 2015. Starmer set about his work with gusto. Just as he had ‘modernised’ the CPS, he was going to do the same with the Labour Party, but with ideological knobs on.

Due process and natural justice not on the agenda

The Leader. Removing the whip from the previous leader must be Starmer’s ultimate ‘Clause 4 moment’, trying to show the Establishment (and the Israel lobby) that the Labour Party was no threat in his hands. You can’t better that. In the internal management of the Party due process and natural justice (I almost put inverted commas around those phrases) are not even on the agenda.

His performances on camera don’t seem to have improved and electorally the Party has performed poorly, as we saw in the recent council elections. The actual politics, insofar as they exist other than attacking the left and squeezing out any hint of 21st century social democracy, consist of the worst of (not that there’s much of a ‘best’ of) New Labour dogma and Blue Labour, dumbing down, and dog whistles. As mentioned above, any hint of an internationalist foreign policy will lead to disciplinary action. I’m sure we’re all familiar with events post April 2020.

The Aftermath. Eagleton concludes that the grip of the Labour right is strong and likely to remain so, in the medium term at the very least. He points out that the last five years have shown that a left leader can’t even be sure of the consistent support of the thirty-two Socialist Campaign Group MPs. The likes of Trickett, Zultana, Burgon, Begum, Trickett, etc are thin on the ground. Laura Pidcock and Smith have announced they are not standing as candidates next time and I don’t imagine they’d get selected anyway, however their local parties voted.

An excellent political biography

Eagleton does suggest that if Party continues to perform poorly, then the right wing could lose interest and that may leave an opening for the left and some of the unions to regain some political traction. But he doubts this and so do I. On a practical level, the author suggests, one task of the left is “To prevent the collapse of the political ecosystem”, a defensive measure but a necessary one.

This is an excellent political biography. If you can’t get round to reading the book, Owen Eagleton has written several very good articles about Starmer in the last few months, and they can be read on Novara (here, here, here and here) and Jacobin (here and here) There was also an extended discussion with Aaron Bastani on Novara on May 8 2022 (here).

As if there were any doubts two years into his leadership, Starmer is attempting to neutralise the Labour Party as a vehicle for any kind of potential progressive change. This book demonstrates that he has had a long apprenticeship in acquiring the mindset and organisational ruthlessness to do just that.