By Mike Kennard, Chair of N.E. Cambridgeshire CLP (personal capacity)

Today all of England’s rivers are now considered to be in poor condition, with our watercourses and beaches polluted with sewage with impunity by privatised water companies. If ever there was an example of what neoliberal economic policies have reduced us to, surely this is it.

Rewind 164 years and we had the first national system of water sewage collection and water treatment. It was as long ago as 1858, when public opinion demanded water treatment when Victorian London suffered “the big stink”. The Thames was at that time so polluted with effluent and factory waste that the stench meant that Parliament, right on the riverside, had to be suspended.

Until the 1970s water and sewage were the responsibility of 198 statutory water undertakings, a mixture of private companies and local authority bodies. These were mostly rationalised by the Heath government in 1973 into 10 regional water authorities (RWAs) and 13 smaller local companies. In Scotland and Northern Ireland water remained in public ownership, and in Wales a public interest company was set up.

The 1974-79 Labour government failed to invest sufficiently in infrastructure and by the time Thatcher was elected in 1979, investment had fallen by more than 60%. Her government imposed borrowing restrictions on the Regional Water Authorities, leading to a further deterioration in infrastructure. When Britain was prosecuted by the EU for its poor standards, it was estimated that capital expenditure required to bring the English system up to scratch was up to £30billion.

Water was privatised at a knock-down price

“Slash, trash and privatise” is an established Tory strategy to plunder the public sector and can be seen most starkly in the decline of the NHS; but it has been a policy followed also with water. Having won the 1987 election, Thatcher was confident enough to press ahead with water privatisation. To make the new Water and Sewerage Companies (WSCs) attractive for investors the Tory government wrote off the industry’s £5bn debt and pumped in a £1.5billion bonus. This meant that the WSCs bought all the reservoirs, pumping stations, sewage treatment works etc – the entire infrastructure – at a knock-down price, £billions below their true value.

As with other privatisations, many individual buyers of a few shares quickly dumped their shares to make a quick profit when the price rose sharply. The big investors stepped in and large finance corporations became the owners of England’s water and sewage system. By 2018, the GMB calculated, 71% of shares in England’s water utilities were owned overseas. Since then, Severn Trent Water, previously majority British owned, has passed mainly into foreign hands.

Why was the industry such an attractive proposition? It is because water is a natural monopoly, with one set of pipes delivering the product and another single system to take away and process waste. Also, demand is inelastic – people and companies cannot survive without water, so there is a guaranteed demand at all times of the year. It is a no-risk investment.

Then again, suppliers, subject to some regulation, can fix their own prices. The GMB report also points to a National Audit Office study which showed that water charges rose at 40% above inflation following privatisation. In 2017, University of Greenwich research showed that consumers in England were paying £2.3bn more for water and sewage than they would have done if the companies had remained in public ownership.

Billions of litres of water lost through leaks every year

The Financial Times found that the WSCs cut critical infrastructure investment by up to 20% in the 30 years following privatisation. The little investment that there has been, was financed by a £56bn mountain of debt – on utilities that were debt-free when they were privatised.

The supposed ‘regulator’ of water utilities, Ofwat, is simply not fit for purpose. Water supply – the storage, treatment and delivery of water, is regulated by Ofwat. Theoretically, it has the power, in extreme cases and in the event of non-compliance of instructions, to levy penalties of up to 10% of any company’s overall turnover.

But it has never done so, in spite of the failure of the water companies to deal with the massive losses of water through leaks, from old pipes that should have been replaced years ago. The industry and Ofwat calculate that over a billion litres of water were lost through leakage last year – equivalent to three and a half lakes the size of Windermere, England’s largest (now suffering serious pollution).

The biggest culprit was the biggest company, Thames Water, which owned up to losing 217 million litres. What’s more, Thames Water is a repeat offender, but the fines that have been levied are considerably less than the investment required to solve the problem and are treated by the company as simply a minor business expense. The company’s turnover is £2.2 bn and a 10% fine – £217million – would certainly concentrate the minds of the board and the shareholders, if Ofwat only had the determination to impose it.

Only £339 million in fines for leaks – in more than 30 years

However, there is little sign that Ofwat is inclined to levy such penalties. It is hardly surprising that Ofwat operates “light touch” regulation, because its Chair, Jonson Cox, is a former chair of Anglian Water. As with most of the statutory regulators, there is a revolving door between industry and regulators, with senior executives passing smoothly between posts. In reality the £339mn fines for leakages levied in 20 years are a minor irritation to the monopoly suppliers.

Part of Ofwat’s remit, the regulation of sewage, is shared by the Environment Agency, which is part of a government department, DEFRA. This agency has often been criticised for inaction, but its opportunity to correct this was impaired in 2015 when its budget was slashed by the then Secretary of State for the Environment – none other than our likely next Prime Minister, Liz Truss.

Both agencies are now rushing to repair their reputations, given the doubling of illegal sewage discharges in three years. The difficulty that they have with this is that in 2010 the Lib-Dem/Tory coalition passed responsibility for monitoring and reporting over to the WSCs themselves. They were allowed to mark their own homework. This month’s efforts by the LibDem Party to in expose the fact that up to 50% of discharges are not recorded is a feeble attempt to draw a veil over their own party’s complicity in the whole privatisation process.

Private companies cannot be relied on to modernise the industry

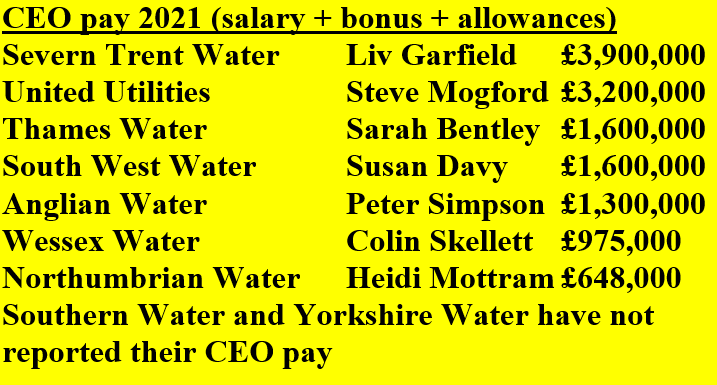

If improvements in water collection and supply and treatment of waste are to be made, we cannot rely on the companies to do this. Privatisation has been a bonanza for them, with profits distributed to shareholders since privatisation of over £72bn. They pay their servants well – the eye-watering pay of CEOs has demonstrated this. (See inset)

These pay packages are not a reward for effective management of services. Between them, these nine companies reported 542,209 hours of combined sewerage overflow – discharge of raw sewage into watercourses and the sea – and that is only what they reported themselves.

The water companies claim that the surge in sewage discharges has been due to abnormal weather conditions, but these have been going on for decades, with England’s natural watercourses some of the most polluted in Europe and scores of beaches losing their Blue Flag status.

As with other privatisations, the policy has been a disaster for consumers and for the environment. The companies have failed to invest and plan for the problems of climate change. Anglian Water has just announced outline plans for two new reservoirs in Fenland and Lincolnshire.

If they are constructed, they will be the first new major reservoirs in the thirty years since privatisation. The cost, up to £2billion, will be funded – you’ve guessed it – by government grants and borrowing. This area of the East of England is the kitchen garden and granary of England, with demands from agriculture for irrigation placing additional stress on watercourses.

Labour must come forward with a plan to brings all essential services and utilities back into public ownership. These services should be managed in the interests of the majority of peoples’ needs and not for the greed of a few large corporations. Privatisation has not led to Thatcher’s so-called “property owning democracy”, but to ownership by a profiteering oligarchy. It has meant a massive transfer of wealth from the working class to the bank accounts of a tiny minority of capitalists.

Compensation is not justified after industry plundered

Opinion polls have shown that there is general popular support for renationalisation of the natural monopolies, and water is near the top of the list for most of those polled, with 84% in support (this was prior to the energy debacle). The Labour Party has calculated that compensating shareholders would around £14.5bn but given the way the industry has been plundered and saddled with debt in the last thirty years, not to mention government subsidies, compensation is not justified.

Tiny investors with handfuls of shares, or perhaps pensions funds, may need to be compensated, but the big financial corporations should not be – most workers would agree that they’ve ‘had their whack’ out of an industry they have plundered and ruined. The accumulated debt must be written off, and a programme of investment implemented, taking full account of the expected problems of climate change. Water saving methods should be encouraged with financial support, such as rainwater capture and improved farming techniques

The regulators must be purged of the place-men of the water companies, with a strengthened remit and adequate resources to operate effectively. Full public ownership, with democratic control and administration, through regional boards, including elected representation of water staff and of local authorities

Only a socialist approach to water supply and treatment can rectify the decades of neglect and plunder by the capitalist owners and provide a consistent supply of clean water and a clean and safe environment.