By Gavin O’Toole

Chilean voters have again confounded expectations less than six months after electing a left-wing president with radical proposals for change by rejecting a new constitution that would have cemented his progressive vision and transformed the country.

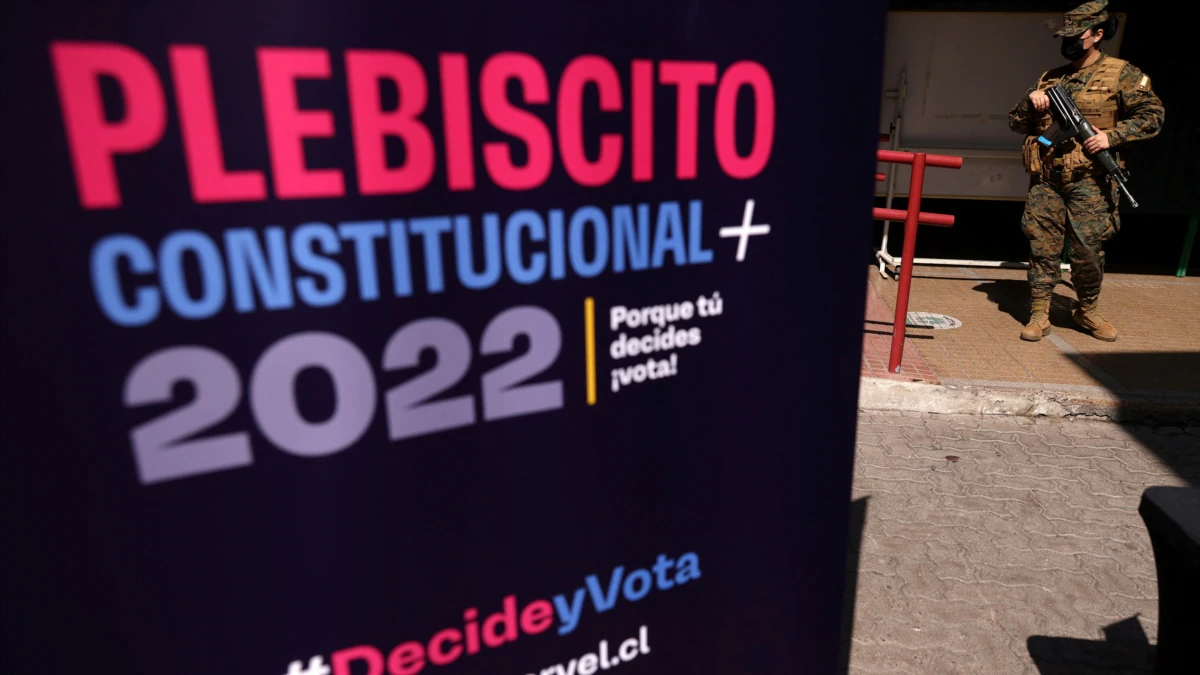

In a referendum on 4 September, they turned down the draft of a new constitution by an unexpectedly high margin (62%)—to the dismay of left-wing groups and indigenous, environmental and human rights activists.

The document would have swept away the 1980 charter enacted by Chile’s brutal military dictator, Pinochet, that enshrined neoliberal principles, by introducing new indigenous and environmental rights, formalising gender equality, fashioning a generous welfare state, and empowering workers with guaranteed labour rights.

The proposed 178-page charter, welcomed by progressive scholars globally as “visionary,” was drafted in 10 months of debate and finalised by a constituent assembly in May.

Its rejection caused surprise because it was a response to violent social protests in 2019—a product of the inequalities prolonged by Pinochet’s constitution—that prompted an overwhelming (80%) majority to support change in a 2020 plebiscite.

The latest vote has inevitably prompted soul-searching on the left about where the draft constitution fell short—but also debate about how progressive change can in fact be achieved in a political landscape so comprehensively dominated by well-funded rightwing actors.

It is felt that, by delaying the efforts of Chile’s president Gabriel Boric, who took office in March with a clear mandate for reform, the setback could spark more protests among frustrated social groups in the vein of 2019.

Obvious explanations

In the post mortem, some potential explanations for the constitution’s rejection have been more obvious than others.

It is likely the outcome includes elements of a protest vote against Boric, who has struggled to stem violent crime, calm tense relations with indigenous activists, and reduce inflation, currently at 13%, as Chile slides into a recession.

There is also little doubt the proposed constitution may have overreached itself by combining radical causes that could find favour among some groups, but not all of them at once. The constitutional convention that laboured for 12 months to draft it represented a broad range of agendas and stances that were by no means without conflicts.

While it is clear that by requiring a two-thirds majority to be approved meant that the draft incorporated many compromises, and some plans—including those to nationalise parts of Chile’s mining sector—were ditched along the way, it also true that Chile’s 1980 constitution is extremely conservative. Putting aside wishful thinking, this meant, tactically at least, that the radical, arguably revolutionary, shift proposed this time in so many areas at once proved potentially too great a leap of faith for many citizens accustomed to the status quo.

Moreover, the draft’s 388 articles made it the longest such document in the world and, according to some critics, at times confusing and self-indulgent—proposing to grant, for example, legal status to glaciers and to defend culturally appropriate food.

The right and many liberal politicians were uneasy about proposed changes to the political system, especially those to the justice system and senate as well as granting greater autonomy to different regions, arguing that these were not causes of popular discontent.

Errors by ‘Apruebo’

The “approve” or Apruebo campaign made strategic errors, not least overestimating people’s willingness to read the extensive text and compare it with the previous constitution. Some polls suggested only about half of Chileans had read the document, and a consensus has formed that the proposals were poorly understood.

Even radicals were uneasy about some proposals, such as plans to declare Chile a “plurinational state,” granting autonomy to its indigenous, principally Mapuche, people.

The Chilean state has conducted a long and bitter repression of the Mapuche in their southern homeland, and Boric already shows signs of repeating past errors by treating the issue of their resistance as primarily one of security—explaining why Apruebo was unable to mobilise indigenous people extensively behind the new constitution.

At the same time, Chileans have been indoctrinated into an official racism insisting that “unity” based on European origins is a key characteristic of a country in which indigenous people have long been assimilated. This willingness to ignore the dispossession of and atrocities towards native peoples is something the British will be familiar with.

Campaign financing

A large gulf in campaign financing between the approve and reject campaigns was another obvious reason for the defeat of the constitutional draft, with leftwing and progressive Apruebo forces vastly outspent by their rightwing “Rechazo” rivals.

Data from Chile’s electoral commission (Servel) a month before the vote indicated that of the total 523 million pesos mobilised in donations that had been registered with the institution by both sides, 89% was destined for Reject and just 11% for Approve.

Of the larger donations considered in detail by Servel (above 1.3 million pesos), Reject secured 728, while Approve gained 222.

Disinformation

While the above factors probably all, to a greater or lesser extent, help to explain the defeat of the progressive forces, the most important variable, and probably the most decisive, was undoubtedly the systemic disinformation campaign waged by Chile’s right.

The wealthy elite bankrolling the Reject campaign enabled it to allocate more than 4.5 times the resources to digital media—123 million pesos—than its Approve opponents (27 million).

This made a considerable difference, because Chile’s mainstream media—newspapers and television stations—are already disproportionately right-wing. That meant Rechazo was able to concentrate its fire on social media: it spent only 4 million pesos more than Apruebo on traditional media (34 million pesos), knowing that these would favour its stance regardless.

The tactics of the Reject campaign, backed by the far-right, since the October 2020 plebiscite, has been to sow falsehoods and division. Social media was the most fertile ground for fake news and, while it is difficult to quantify the impact this had on polls, some studies suggest 65% of people may have encountered misinformation.

The most common lies going viral included those based on claims by Felipe Kast—nephew of José Antonio Kast, a far-right supporter of Pinochet who lost to Boric in December’s election—that the new constitution would permit abortion up to the ninth month of a pregnancy.

Another recurring falsehood was that a new right to housing would ban people from owning private property or empower the state to confiscate voters’ homes.

Rightwing campaigners alleged Chile’s name, flag and anthem would be changed, thatprisoners and recent migrants would be allowed to vote, and increasingly targeted the electoral commission itself.

Such was the concern about the impact of disinformation that Democrats in the US congress wrote to the CEOs of Facebook parent company Meta, Twitter, and Tik Tok to share their “grave and urgent concerns” and implore them to “act with urgency” against “patently false claims” about the new constitution.

Culprits

Negative social media campaigning by far-right activists mimicked the tactics used by figures such as Donald Trump in the US and Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, attacking Chile’s electoral system and threatening to ignore the result of the referendum.

Meanwhile, Chile’s right-wing corporate media did not stand idly by, often responding to fake news on social media with its own follow-up stories.

Media ownership in the country remains heavily concentrated—just two groups own the majority of printed media—and hence firmly in the grip of an elite that has benefited enormously from the Pinochet economic model.

El Mercurio, Chile’s main rightwing national daily newspaper that operates a network of 19 regional dailies and 32 radio stations across the country spared no effort in distorting the constitutional process.

This newspaper came to global attention in 2021 for publishing what was described by the local Jewish community as “an apology for Nazism” after printing an illustrated article commemorating the life of Hermann Göring, the German war criminal.

In 2019, Chilean journalists picketed El Mercurio’s offices after it published an insert praising the Pinochet dictatorship that ruled the country from 1973 to 1990. Some 60 signatories paid nearly US$20,000 to publish the insert on 11 September—the date of Pinochet’s US-backed coup against the socialist president Salvador Allende.

Agustin Edwards, El Mercurio’s owner in 1973 and one of the country’s richest people, was a cheerleader for Pinochet, and research suggests US President Richard Nixon approved covert payments to him totalling US$2m to help destabilise Allende.

There is little surprise in the use of fake news and hate to undermine the left, both of which were distinguishing characteristics of the electoral campaign of the elections in which Boric was elected president.

The progressive international press agency, Pressenza, has shown that key culprits financing many of these activities in Chile are local foundations of the Atlas Network, a far-right policy institute funded by some of the biggest fortunes and companies in the US.

Leading right-wing figures who have a strong presence on social media in Chile include Kast, former Pinochet planning minister Sergio Melnick, and vlogger Teresa Marinovic.

Moreover, right-wing Chileans found eager support from a global smear campaign led by the capitalist media such as the Economist—which helped to foment Pinochet’s coup against Allende—which criticised the draft constitution as a “left-wing wish list”, and the Financial Times, which suggested it would damage Chile’s investment climate.

Where now?

While rejection of the proposed new constitution is undoubtedly a setback for the left, the document does create a route map for progressive change in the country.

It is clear that most of those who voted to reject the draft had also voted in 2020 in favour of replacing the Pinochet-era charter, suggesting the desire for constitutional reform persists.

The rejection complicates Boric’s agenda by putting the ball in the court of congress, where rightwing forces with almost half of the seats will be able to veto reform efforts.

Boric had stated prior to the referendum that, should the draft be rejected, a redraft should ensue, and some opposition members in congress have indicated support for restarting the process.

Other lawmakers have suggested the best way forward would be to amend Chile’s extant constitution—an option rejected prior to the 2020 plebiscite because of the difficulty of doing so.

Nonetheless, it is clear that support for a new constitution has grown since Chile’s return to democracy in 1990, and in 2015 then president Michelle Bachelet spearheaded efforts to do so, even though these failed.

Further delays—and the constraint the rejection puts on implementing Boric’s progressive agenda—could fuel frustrations that erupt in further rioting and social unrest.

That would pose a challenge to the Chilean left – to provide a lead and a focus for popular discontent and further reform or risk being by-passed.