By Michael Roberts

Danish Social Democrat leader Mette Frederiksen achieved a successful result in yesterday’s general election. The SD polled 27.5% of the vote (the turnout was down but still over 80%) and increased its seats in parliament to 50. Frederiksen was forced into an early election with the withdrawal of one of the centre parties in her previous ‘left’ coalition over the so-called scandal of the mink farm cull carried out during the COVID pandemic, which wiped out this disgusting industry but lost Danish farmers export revenues.

Despite this, the left coalition has still managed to achieve the 90 seats necessary to ensure its continuation in government, although the two main parties to the left of the SD lost ground. That’s because the main opposition party, the Liberals, and the previously strong anti-immigrant Democrats, took a drubbing (mainly because the SD adopted many of their proposed policies).

Ironically, this result is not what Frederiksen wants. She has been calling for basically a national government based on a coalition with centre parties and ditching the left. The new development in the result was the emergence of the Moderates, a party recently formed by the previous right-wing PM Lars Lokke Rasmussen, which gained 16 seats. Both Frederiksen and Rasmussen have said they would like to see a centrist government to minimise the influence of smaller parties.

Social Democrat leaders want a centrist coalition

Former Social Democrat prime minister Helle Thorning-Schmidt explained the strategy: “It could be a new way of doing things. We’ve never had so much talk about this middle ground and finding compromises in the middle.” And Jakob Engel-Schmidt, political head of the Moderates, added: “With the security situation in Europe, the energy crisis, the inflation crisis, we believe that politicians need to come together and make certain reforms that takes care of the welfare state for the future.” Note that last comment on the ‘welfare state’.

The Danish election has followed a recent election in Sweden which saw the rise of an anti-immigrant party, the Democrats and the defeat of the left-centre coalition. But even if the result was politically different in the vote and government with Denmark, the general trend of the move to the right by the Social Democrats in all the Nordic countries over the past few decades has led to a gradual and accelerating reduction in the formerly famous social democratic welfare state model.

The story of the degrading of the social-democratic model in Sweden is well documented in a recent paper by Viktor Skyrman and colleagues at the Stockholm School of Economics. And it has been much the same in Denmark and Norway. Yes, Denmark may have the laurel of the happiest country in the world, but that does mean that, as in every capitalist economy, everybody is happy.

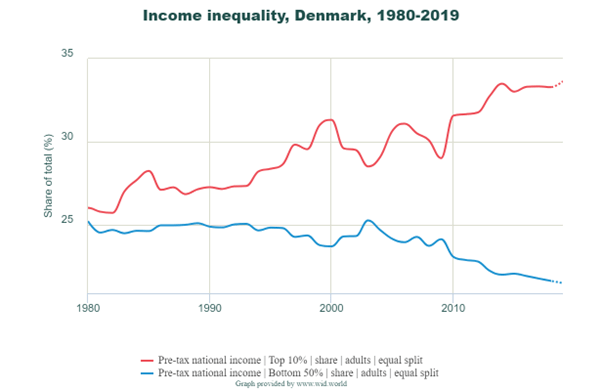

Income inequality

Inequality of income and personal wealth has been increasing since the early 1980s, with a particularly sharp rise in the share of personal income going to the top 10% since the end of the Great Recession in 2009. The share of income going to the bottom 50% of income earners has cratered from 25% in 1980 to less than 10% now!

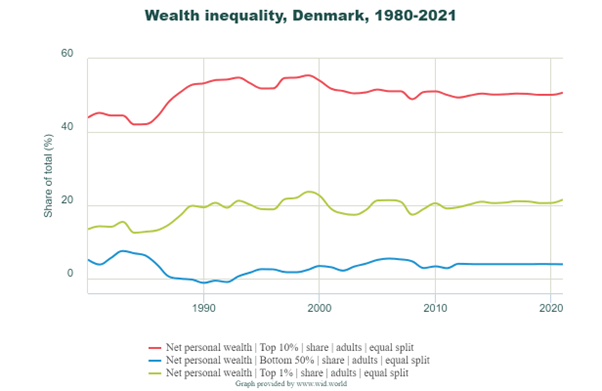

Wealth inequality

But inequality of wealth is even worse – as it is in Norway and Sweden. The rule of the wealthy and big capital (often controlled by a few mega rich families) is a feature. The bottom 50% of adults in Denmark have less than 5% of total personal wealth while the top 10% have 50% and the top 1% over 20%. Social democracy is more a name than reality.

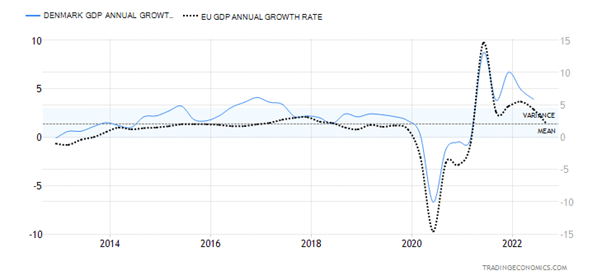

GDP growth

The small Danish economy usually does better than most in the EU. Average real GDP growth has been higher than the EU average and the impact of the COVID slump less.

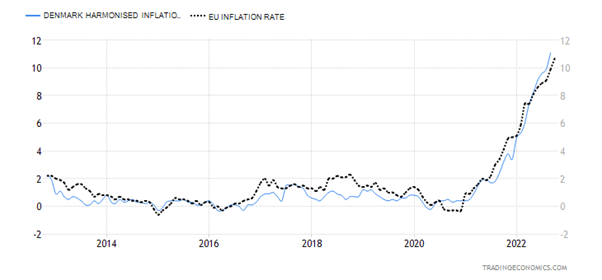

Inflation rate

But Denmark is not escaping the general malaise in the world economy as inflation rates rocket and interest rates rise.

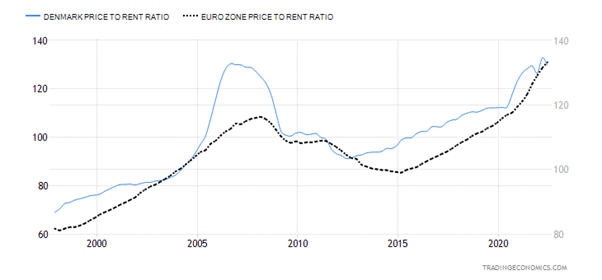

House prices

The house price boom in Denmark (as in other EU countries) that has boosted middle-class wealth is about to take a turn down.

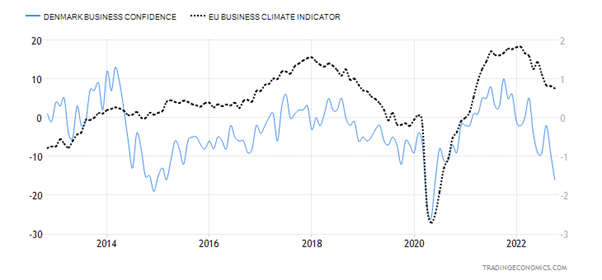

Business confidence

Another round of fiscal austerity and welfare cuts will be on the agenda of any ‘national’ government. Danish business is beginning to struggle and profitability is set to fall.

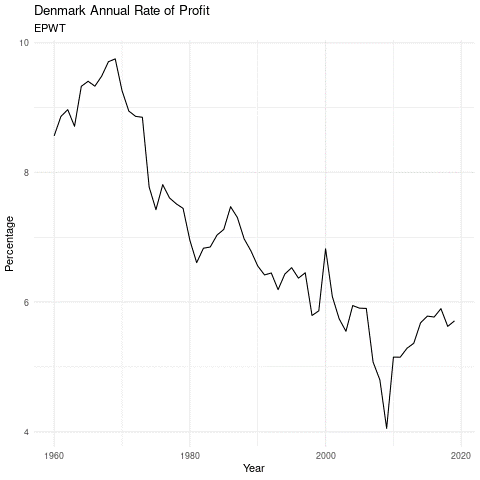

Decline in profitability

And it is the long-term decline in profitability that has set the base for the gradual reduction in the social democratic model in the last 40 years.

From the blog of Michael Roberts. The original, with all charts and hyperlinks, can be found here.