By the Socialisten Editorial Board

The Socialisten editorial board has kindly provided us with a translation of their article on the Danish general election that was originally published here on 7 November 2022.

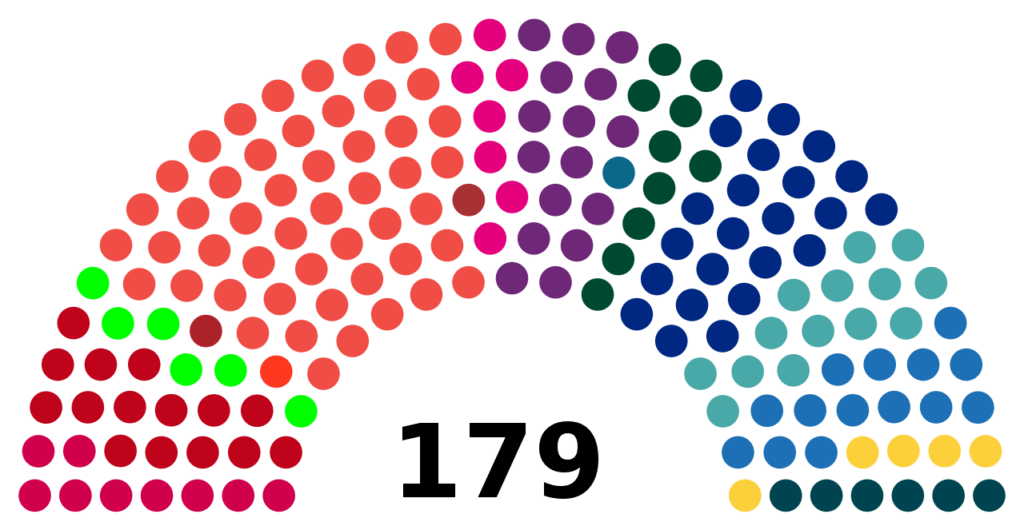

It was not until the late hours of the night on Wednesday 2 November that the general election was decided. Even with 99% of the votes counted, it was uncertain how the decisive mandates would turn out. In the end, it ended with a narrow victory for Mette Frederiksen, the present PM and president of the Social-Democratic Party, who has exactly 90 MP’s behind her (out of 179 seats in parliament).

The elections were not only very close. They were also characterized by great uncertainty in forecasts and opinion polls, because as many as 24% of voters were in doubt about where their vote should be cast. Over 40% of voters voted for a different party than the one they voted for in 2019. This has been reflected in a parliament with as many as 12 parties, where only two parties have over 10 percent of the vote. It is an expression of an unstable political and economic situation, with rapid and sudden changes.

If you look at the old traditional parties in power (the Social Democrats, Liberals, Radicals and Conservatives), only the Social Democrats progressed (1.6%), while the others suffered defeat; The Liberals lost a whopping 10.1%, the Conservatives 1.1% and the Radicals (a social liberalist party) 4.8%. This means that the old parties together can only muster 50.1% of the vote, which is an unprecedented low figure.

The Danish People’s Party, a far-right party which very recently (2015) was the second largest party with as much as 20% of the vote, has been completely destroyed and had to fight just to preserve any parliamentary representation at all. They ended up with just 2.6% of the vote.

The election campaign

In these elections, two new parties entered. Støjberg’s Danish Democrats got 8.1% of the vote (14 seats). Støjberg, a former right-wing minister, presented herself as a champion for residents of rural areas, despite the fact that in her time as a politician she helped make some of the most centralizing reforms the country has ever seen, which led to the closure of hospitals, primary schools, etc.

But in the lack of a clear alternative from the left-wing parties, Støjberg managed to address themes such as the closure of shops in rural areas and the rising energy prices, which particularly affect people in the countryside, where houses are traditionally heated with natural gas or oil. This partly also explains her high personal vote count (over 47,000) in North Jutland.

The other new party that won a considerable victory and entered parliament was Lars Løkke’s Moderates. Løkke is a former PM who split from his old party, the Liberals and created a new party with the aim of organizing a national coalition-government. He won a whopping 9.3% of the vote, corresponding to 16 mandates. However, the Social Democrats are not dependent on the Moderates’ mandates in order to form a majority, which was Lars Løkke’s clear objective.

During the election campaign, Løkke tried to pretend that he was some kind of outsider who wanted to conduct politics “in a completely new way”. But towards the end of the election campaign it became more and more clear that he is still 100% right wing liberalist. It was revealed that he intends to destroy the national pension and that he wanted “reforms” (ie extensive cuts to welfare and measures that increase the labour supply, so that wages and working conditions can deteriorate).

The two old bourgeois parties, Conservative and Liberals, had miserable results. The Liberals lost 20 mandates, and now only have 23 seats, while the Conservatives lost 2 seats, so they now only have 10 MP’s. In contrast to Lars Løkke, they chose to put all their energy into attacking Mette Frederiksen’s so-called “authoritarianism” in connection with the mink case and exposing her as a tyrant. It backfired completely.

The Mink scandal, which the right-wing parties tried to use against Mette Frederiksen, took place in November 2020, when the government decided to execute all mink cattle in Denmark and temporarily shut down that business sector, because of the fear that the coronavirus could mutate in mink cattle.

While the Liberals and Conservatives tried to denounce Frederiksen for having acted against the mink farmers without having the legal framework, big parts of the population remained hesitant to support this campaign. Firstly, large parts of the working class are not particularly sympathetic towards the mink breeders, who received compensation of a whopping 17 billion kroner. Secondly, the intervention against the mink breeders was in many ways a correct intervention, because it put public health – in the middle of the Corona virus crisis – above the interests of business. The fact that the government ran into legal problems was only due to the fact that they had to rush the intervention through, a result of them having waited too long for the sake of the business world instead of having intervened earlier. Thirdly, it is complete hypocrisy when the Liberals and Conservatives attack Mette Frederiksen for being in power. During their own periods of government, they were known for their so-called showdown with the “expert power”, which consisted of shutting down expert committees that disagreed with them, just as they, among other things, chose to shut down a commission inquiry into the Iraq war.

During the election campaign, it became clear that the bourgeois blue bloc wanted vicious attacks on the hard-fought rights of the working class. They attempted to camouflage this as tax cuts at the bottom (“lower tax on work”), but their real aim was to cut between 6 and 100 billion kroner on welfare. Inger Støjberg tried to camouflage her attacks as “de-centralisation” and Lars Løkke camouflaged it as a “proposal for broad cooperation”.

The reality is that the Danish upper class is impatient for reforms that increase their multibillion-dollar fortunes by increasing the labour supply and thereby depressing wages and living conditions. The bourgeois explained it clearly by calling the Social-Democratic government of 2019-22 “unambitious”, because there had been a 3-year reform break. Lars Løkke’s plans for a broad government were then also justified as an attempt to detach Social Democracy from the “extreme left wing” (a reference to the Red Green Alliance) and the right-wing from the ultra-racist parties on the far right.

For us activists in the labour movement, we have to admit that Social Democracy has pursued far too little red politics and far too much right-wing agendas. Among other things, they have destroyed the new apprentices’ daily unemployment benefits. But according to the parties of the capitalists, it is obviously far from enough. Between the lines, they showed that their plans are an attack on unemployment benefit, pensions, as well as further privatisation of the health sector and the rest of welfare (disguised as “free choice for the citizen”).

While the Conservatives and Liberals are now extremely weakened, Lars Løkke, together with the social-liberalist party called The Radicals, appear to be bourgeois Denmark’s best hope for implementing some of the anti-worker reforms, if they will manage to form a reactionary government across the centre.

The radicals – a small bourgeois employers party

The Radicals, a social-liberalist party that defines itself as “centre-ground”, had to see themselves almost blown to pieces. Their entire election manifesto revealed them as a small parasitic bourgeois party. Parasitic because, like a small parasite, they suck blood from the workers’ parties, which they constantly try to get to carry out bourgeois politics.

This year, they decided to overthrow the social-democratic government to get “a new start where the voters can appoint a new team”. In reality, Sofie Carsten Nielsen, their leader, believed that they themselves should be in the government, preferably together with other bourgeois parties, so that all the attacks they could not get through in the current government could be carried out.

So they toppled Mette Frederiksen, only to immediately designate her again. Fortunately, the voters decided to punish this small bourgeois employers’ party.

The social-democrats

The Social Democracy reaped an increase of approx. 1.6%, corresponding to two additional seats in parliament. This is partly explained by the unsuccessful right-wing campaign and partly because of the fact that many people remember the Corona virus pandemic, where Denmark despite everything went through easier than many other countries, with fewer deaths and fewer lost jobs. But it is also about the fact that the parties to the left of the Social-democrats, especially the Red Green Alliance, failed to show another path that could challenge the top of the Social Democracy.

Mette Frederiksen led an election campaign full of contradictions. On the one hand, she talked about better pay for public servants, on the other hand, she continued to call for the formation of a national coalition government together with the right-wing parties and also nodded yes to proposals for “debureaucratisation” in the public sector (read: cuts). This paradox was not exploited sufficiently by the left-wing, which should have had much more offensive criticism of the central government project.

The Social Democrats in coalition with the bourgeois?

When Mette Frederiksen called the election, she surprised both SF (Socialist Peoples’ Party) and Enhedslisten (Red Green Alliance), but not least her own social democratic rank and file, by announcing that the goal was a national coalition government together with the right-wing. A large number of mayors and local chairmen in the social democratic rank and file have openly expressed their skepticism about the new course. Nor did it cause celebration among the activists of the trade union movement, who well remember Helle Thorning’s government of counter-reforms which was in power from 2011-2015.

Unfortunately, the leaders of the Trade Union Organisation (FH) chose again and again to behave passively, which they have done for the last 20 years, while the living conditions of the workers have been “reformed” beyond recognition.

A new broad government between the social democracy and the bourgeois can only become a government on a bourgeois austerity basis.

The ruling class in Denmark has become impatient, they want to pay less tax and they insist on reforms that open up wage pressure from imported labour from Asia, as well as forcing the sick and elderly to stay on the labour market, just as the Social Democrats want to pressure more young people to early entry into the labour market by shortening their education.

Such a coalition will pave the way for a new bourgeois government with further attacks as a result, as we saw after Helle Thorning. And this despite the fact that there was a so-called “red” majority, if you include the Radicals. But with a partial destruction of The radicals, all conditions for blowing them away were present. We can only encourage the trade union movement and the social democratic rank and file to put pressure on their leadership, to get them away from forming a bourgeois anti-worker government.

The campaign of the Red Green Alliance

The Red Green Alliance (RGA), in Danish called the Unity-list, Enhedslisten, is a coalition between a number of parties smaller left-wing parties, chiefly the Danish Communist Party, that emerged in 1989. Up until the elections it commanded around 7% of the vote and held 13 seats in parliament. But in these elections, The RGA lost as many as 4 mandates and went back 1.8%. The party lost around 70,000 votes. The RGA lost votes everywhere in the country, including in Copenhagen, where it lost as much as 3%.

This is nothing less than a disaster, which must be discussed internally in the party. We should not try to dismiss the results with foolish excuses such as a “tactical vote” for the small Green party called The Alternative.

Such excuses are used by the supporters of the RGA’s recent turn to the right, in an attempt to prevent criticism of the fact that their political course has led to yet another defeat.

In reality, the RGA lost voters to both Social-democracy, SF (Socialist Peoples’ Party), Alternativet, Frie Grønne (Free Greens) and to those who simply chose to stay at home. The Free Greens, who appeared in words as revolutionaries, harvested approximately 30,000 votes and became the largest party in Tingbjerg and Gellerup, as well as the second largest in Vollsmose, some of the low-income areas with a big immigrant residency.

Turnout was also historically low, which meant that approximately 30,000 fewer people voted. The two numbers alone give approximately 60,000 votes, which a clearly left-wing alternative could absolutely have won over. There is also a growth in the number of blank votes, which increased by over 19,000.

The RGA result is not the fault of the other parties. It is RGA’s own fault. It is now the second election in a row that the party has gone backwards, and in reality it has gone back almost constantly in the opinion polls since 2013. In 2013, RGA was polling close to 13% of the vote, at a time when it was opposing Thorning government’s right turn, but when the opposition waned and it became clear that the RGA would not act on its threats, the voter exodus began.

Since then, the RGA has turned to the right, with the so-called “renewal process” accellerating. This has meant that the leadership has moderated its policy in more and more areas. Opposition to the EU and NATO has been toned down. The RGA Parliamentary group entered a number of settlements in the Danish Parliament, some of which have led to cuts and which later, following pressure from the grassroots, they had to withdraw from. This applies, for example, to the agreement on the relocation of study places, which has meant massive cuts at the universities and professional bachelor’s programmes.

Other agreements that Enhedslisten has voted for include the ‘waste settlement’, which leads to the privatisation of the municipal waste sector, the state racist special law for Ukrainian refugees, a police settlement which means more surveillance, an agreement on CO2 capture and storage, which opens up massive use of carbon capture and storage (CCS) on everything from polluting industries to municipal waste incinerators and biomass plants and a very mediocre sub-agreement on infrastructure.

It is true that the RGA has also achieved some improvements during the period. The improvements have typically been very small in relation to the state’s budgets and amount to millions, while increased military expenditure, for example, amounts to enormous amounts in the billions.

The problem has also been that it has been invisible to the voters to a certain extent, since the negotiations have been “loyally” held to the government offices. That way, no one has known what the RGA has been through. When you later hailed the settlements as great victories, it looked like you were 100% in agreement with the government’s line.

And we have seen several times how the affected users and employees have raged against the restrictions in the same agreements that RGA has welcomed, most recently e.g. with the underfunded psychiatry-agreement and the limited cash assistance reform.

Instead, it should have been openly stated what an improvement would have looked like if the RGA alone could decide. The problem is that the so-called “renewal” of the RGA is no renewal at all, but a process led by a group of people who have lost faith that ordinary workers and young people can be won over to a socialist program and that it is possible to secure significant improvements. That is why they want to “social-democratize” the RGA.

Generally speaking, the RGA has been too uncritical of the Social Democratic government. The voters were reminded of that during the election campaign itself, when the party’s immigration spokesperson suddenly stated in the daily newspaper Politiken that the RGA could live with a Danish reception centre for asylum seekers in the dictatorship state of Rwanda. In other words, that they were willing to appease the government on that issue. The party subsequently sat down and stated that it was unacceptable, but the damage had been done and thousands were left with the impression that the RGA’s support was for sale and that the price was actually not very high.

It is true that many activists and local candidates for the RGA made a huge effort and also often put forward good and correct demands. But the election campaign is one thing, the last three years are another. Voters judge a party not just on what they say, but also on what they do. Instead of having been a more or less uncritical support party, the RGA should have attacked the government’s failure in the area of climate change, strongly opposed militarisation and explained that it means further cuts in municipalities and regions.

It should have stayed out of unprincipled deals and instead acted as a consistent left opposition to the government’s rightward drift. In this way, it would also have a clear opportunity to win over people in the base of SF (Socialist Peoples’ Party) and the Social Democrats. Unfortunately, this is not the way the parliamentary group has worked for the past three years. Therefore, they have come to resemble the Social Democrats and SF in many respects.

It is a historical law that when there are three workers’ parties pursuing the same policy, the workers always orientate themselves towards the largest. Workers are practical people. If parties pursue the same policy, then better vote for those who have a greater realistic chance of getting it implemented.

If you look at the last few election results, it becomes clear that the RGA only advances when it appears as something radically different from Social-democrats and SF (Socialist Peoples’ Party). This was clearly seen in 2011, when both the Social Democratic Party with Thorning in the lead and the SF with Søvndal had begun to move significantly to the right, as a warm-up for them to form a government together with the Radikals. At that time the RGA protested strongly and it made great progress, from 2.2 to 6.7% of the vote. Quite the opposite today, where voters could not tell the difference between the three parties.

It also has to be remembered, that even though the RGA reached 7.3% in 2015, it was actually a very disappointing result. In 2013, RGA stood at close to 15% by strongly criticizing the Thorning government’s bourgeois cuts. But due to a downplaying of our criticism and politics, RGA did not achieve the result they could have gotten in 2015. Then later, in 2019, RGA’s election campaign was extremely moderate and every hint of left-wing politics was removed almost clinically, which again led to a disappointing election result.

What now?

Government negotiations are now underway and they may well become protracted. Mette Frederiksen has maintained her desire for a national unity government. The ruling class is divided on this question. While Jakob Elleman and Søren Pape (leaders of the Liberals and Conservative Parties) stubbornly oppose it, there are more and more voices in and around the Liberals who see it as a good idea. Parts of the bourgeois commentator world, Børsen and Politiken, also see it as a good idea. The same is said by the CEO of the Industrial Employers’ Organisation, who in a major interview recommended that the Liberals and Conservatives join a centre government.

Inside the Social Democratic Party, the mood is more mixed. When it became clear that the election result allowed the current majority to continue, the audience began to break into cheers and shout “Denmark needs a social-democratic government again!”. Many ordinary workers look – correctly – with fear at what right-wing economic reforms Lars Løkke will be able to enforce in a national coalition government.

It is unknown how exactly Mette Frederiksen can form the government, but it is almost certain that it will happen in collaboration with either the Radicals or the Moderates. There has also been talk of the possibility of a definite majority government between Social-democrats, Socialist Peoples’ Party, the Radicals and the Moderates. A centrist government, regardless of whether it is with the Radicals or with the Moderates, will be a disaster for ordinary working people. The state budgets are severely strained because of the large military expenditure that has been adopted, but also because there are now plans to quickly make a new defense settlement. That will mean crazy sums for weapons and military hardware.

At the same time, the ruling class in Denmark wants to make labour supply reforms, because that is the only cure they see against inflation. They want to make labour cheaper (read: destroy workers’ wages and working conditions), by forcing even more people into miserable low-wage jobs. It is partly about attacking the Students benefits, attacking unemployment benefit, reducing pensions even more, etc.

The RGA must make it clear that they cannot in any way be a support party for a government that wants to pursue bourgeois politics. Therefore, we must clearly refuse to support a social democratic government with the Moderates and/or the Radical Left, who both want to cut welfare and implement reforms that make life harder for the sick and unemployed.

With an acute energy crisis, soaring inflation and the possibility of an economic recession, we are entering a period of continued instability and rapid political change. Thousands of workers and youth will search for political answers. The RGA can play an important role if the party is orients itself towards combining the work in parliament with the work in the movements outside and manages to provide socialist answers that both address the acute questions of the energy crisis and inflation and connect them to radical demands that point beyond the framework of the capitalist system.

Source of photos: News Oresund / CC 2.0