By Michael Roberts

There has been a burst of optimism about the state of the world economy since the beginning of the year. At the end of last year, the consensus of many economic forecasts was that the major economies were heading into a slump in 2023. Most of the international agencies were forecasting a slowdown in economic growth at best and at worst a contraction in national outputs of the major economies. I too posted a forecast for 2023 as “the impending slump”.

But now the mood has changed. The consensus view is that the G7 economies (with the sorry exception of the UK) will avoid a slump this year. Sure, there will be slowdown compared to 2022, but the major economies are going to achieve a ‘soft landing’ or even no landing at all, but just motor on, if at a low rate of growth. The international agencies have upgraded their forecast for growth.

Why the capitalist forecasters are more optimistic

Whereas the Eurozone economies were expected to contract in 2023 because of the energy crisis and Russia-Ukraine war, now the EU Commission reckons that the region will avoid a ‘technical recession’ this year. The winter was warmer than expected and oil and gas reserves built up by Eurozone governments (at great expense) have managed to avoid power outages despite applying sanctions on Russian energy exports. Unemployment has stayed low and consumers have continued to spend more, using up savings built up during the COVID lockdowns. At least, that is the explanation provided for renewed optimism.

The IMF too has joined the party in revising up its forecasts. And the IMF chief economist now firmly rules out a recession in the major economies this year (again with the exception of the UK). Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, said 2023 “could well represent a turning point”, with economic conditions improving in subsequent years. “We are well away from any [sign of] global recession.” Its world growth forecast for this year has been lifted from a previous 2.7% to 2.9%, basing its estimate, not just on a warm winter in Europe but also on the opening-up of the Chinese economy after the end of its zero-COVID policy. This would boost production globally and also demand for European exports. Half of this year’s forecast expansion will come from China and India alone as the major advanced economies will slow to 1-2% growth, with the UK the only major economy contracting.

As for the US, the mood is very positive. Last month’s net job figures showed a jump of over 500,000, with the official unemployment rate falling to 3.4%, its lowest in 54 years! Also the latest retail sales data showed a sharp jump up in January, suggesting Americans are continuing to spend and keep the economy buoyant. As the labour market is booming and consumers are spending, all talk of a recession this year is clearly baloney.

But deeper investigation shows a less rosy picture

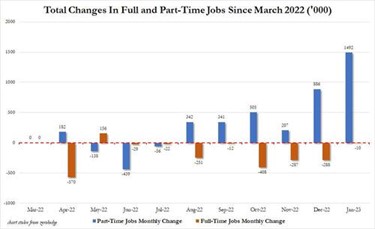

But wait, let’s examine the data more closely. Continuing with the US economy, the best performing among the top seven (G7) capitalist economies, much of the last year’s increase in employment and the low unemployment rate can be explained by statistical adjustments and by the large number of people who have not returned to work after COVID, thus causing a very tight labour market. January saw a statistical adjustment that added in an extra 1.6m to add to the payrolls that had been missing from data. And here’s the other thing. Back last March 2022, there were 132.6m Americans in full-time work. In January 2023, there were 132.6m. So there was no increase in full-time jobs in ten months. Instead part-time jobs rose by 1.5m! What we have is a ‘strong’ labour market where workers can only get part-time, often casual work, and where they often take two or three jobs to make ends meet in the face of rocketing prices of necessities.

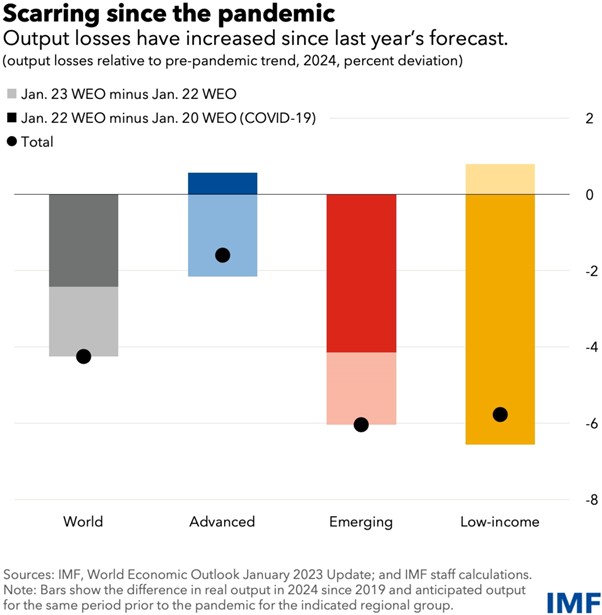

And remember even if the international agencies have raised their forecasts for this year just a little, they are still forecasting very weak growth in 2023 – indeed economic growth way below the ten year average pre-pandemic, which in turn was below the average in the years before the Great Recession of 2008. The IMF calculates that the pandemic slump has ‘scarred’ economies to the tune of an average 4% points loss of real output since 2019 relative to trend growth before.

Growth forecasts are still low historically

Even though the IMF has ticked its forecast up along with a more optimistic view of this year’s economic activity, its 2.9% global forecast is still well below the average of 3.8% a year during the Long Depression of the 2010s, which in turn was a downgrade of growth before the Great Recession of 2008-9. The fastest growing G7 economy this year will be Japan at 1.8%. The UK will be the only economy in a slump. The Eurozone is forecast to grow only 0.7%.

The Eurozone economy grew just 0.1% in Q4 2022, so no contraction. However, this figure included the ludicrous GDP growth recorded for Ireland. Germany and Italy contracted while France just escaped contraction. Outside the Eurozone, both Sweden and the UK contracted. Overall investment is still below the level at the end of 2019.

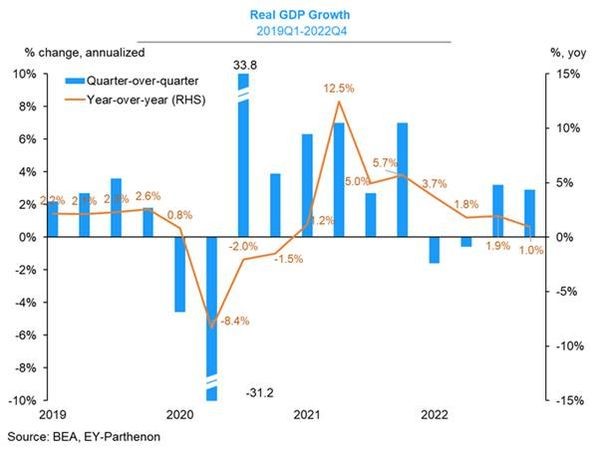

US economy struggling to grow

It’s a similar story in the US. US real GDP growth has slowed from 5.4% year on year in Q4 2021 to just 1.0% in Q4 2022 (by Greg Daco). More significant, inventories (ie stockpiling goods) contributed over half the annual rate in Q4. Sales to Americans (consumers and producers) were virtually flat, while business investment rose at under a 2% rate.

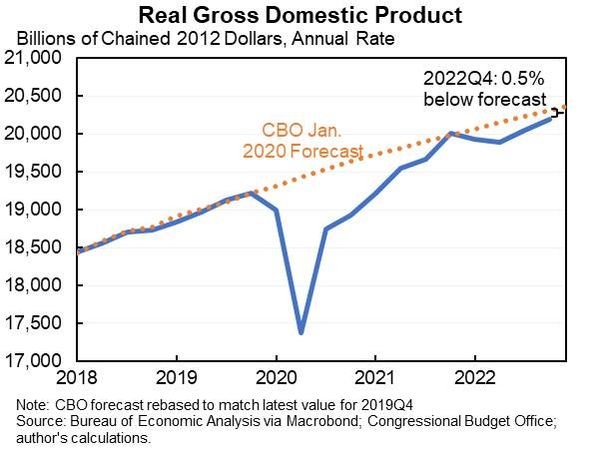

US real GDP growth has finally returned to its pre-pandemic trend rate but after three years of recession and below trend growth (by Jason Furman).

Signs that the US is heading for recession

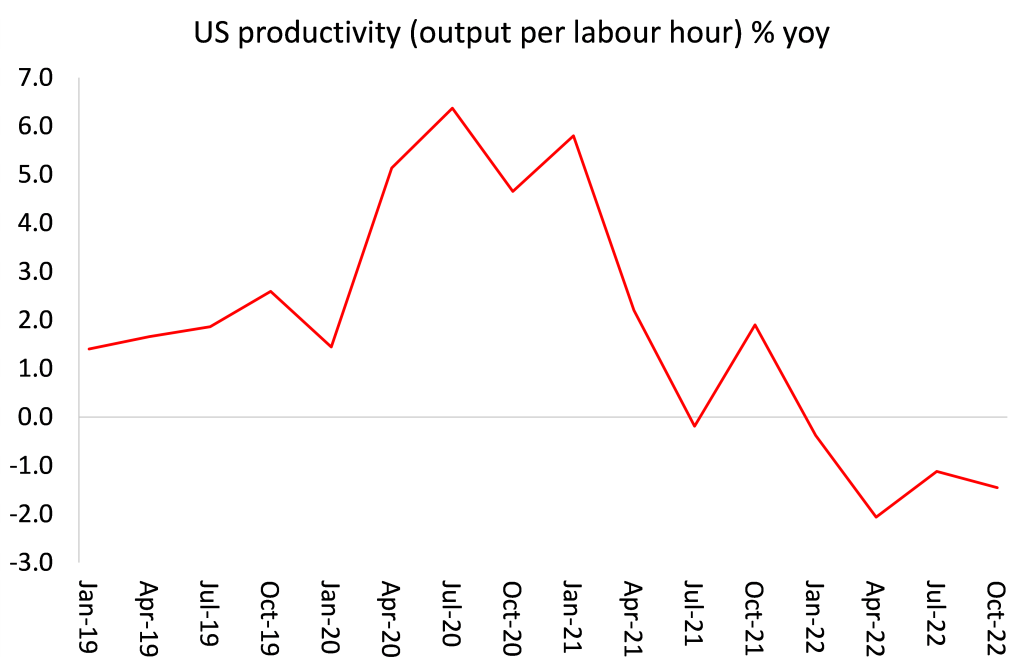

And let’s weigh in with the factors that suggest the US is heading for recession this year. First, a sizeable section of the economy is already contracting. The housing market has been slumping for months. Productivity growth has been virtually non-existent, thus keeping output growth dependent more employees and driving up production costs per unit of output, both for raw materials and for wages.

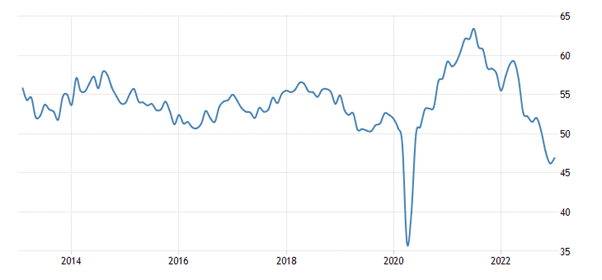

Indeed, the manufacturing sector in most major economies is already contracting. The US manufacturing PMI ( a measure of activity) is well below the contraction point of 50.

And there is the rising cost of borrowing. The Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of England are all engaged in raising their policy rates of interest, ostensibly to reduce inflation rates that have rocketed in the last year or so. I have argued in several posts that the inflationary spike is not caused either by previously ‘excessive’ monetary injections or by ‘excessive’ demand generated by too much government spending – and certainly not from ‘excessive’ wage demands by workers. The cause lies with the failure of the capitalist sector to supply enough to meet the demands of workers and capitalists as economies came out of the COVID slump; particularly in energy and food – and of course, the fossil fuel and other companies have taken advantage of shortages by raising prices.

Inflation and the cost of borrowing

As Andrew Bailey, governor of the Bank of England, once said: “Monetary policy will not increase the supply of semiconductor chips, it will not increase the amount of wind (no, really), and nor will it produce more HGV drivers.” Nevertheless, the central banks continue with their ‘shock therapy’, which is only increasing the cost of borrowing and servicing existing debt while having little effect on inflation rates.

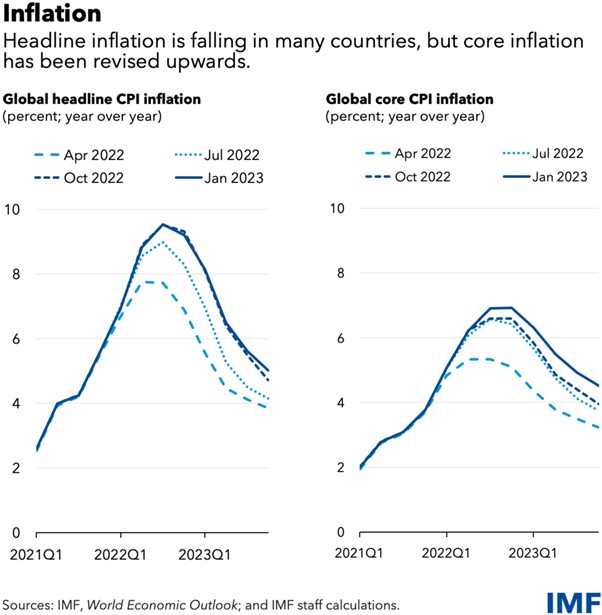

It’s true that headline inflation has peaked and is beginning to fall. But ECB board member Isabel Schnabel admitted only recently that the recent fallback in the headline inflation rate was not down to ECB policy. “You can’t say monetary policy is having such an impact that we can hope for inflation to reach our 2% target in the medium term.”

Inflation is subsiding a little mainly due to the peaking of energy and food prices. ‘Core’ inflation (excluding food and energy) is proving ‘stickier’. According to the IMF, even by 2024, projected average annual headline and core inflation will still be above pre-pandemic levels in more than 80 percent of countries.

Moreover, this is the inflation rate, not the level of prices. Even if inflation slows, it still means that price levels will remain much higher than they were before the pandemic – 15% higher in the case of the US, and much higher in other economies. That is a permanent hit to living standards and the ability to spend more, as wage increases and now even profit rises cannot keep up.

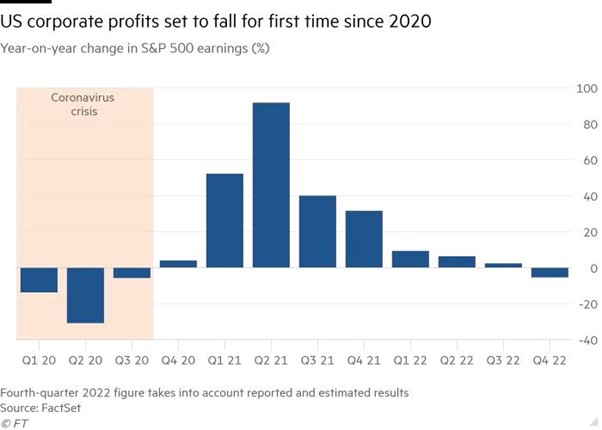

US corporate profits falling

And what happens to profits is key in a capitalist economy. During the recovery in 2021 after the COVID slump, profits rocketed, partly from government subsidies and partly from the ability to raise prices. But now the worm is turning. Rising interest costs are squeezing at one end, while slowing economic growth and sales are squeezing at the other. Profit margins are falling from highs. According to FactSet, US corporate operating profits (sales minus costs) are falling.

As I have argued ad nauseam, if profits for capitalists start to fall and continue to fall, that will lead to an ‘investment strike’ and the laying off of workers in order to reduce losses. Already we have seen that falling profits in the media-tech sector has meant sharp reductions in workforces. That will spread to the rest of the economy if other sectors cut back.

‘High frequency’ indicators signal a recession in the US

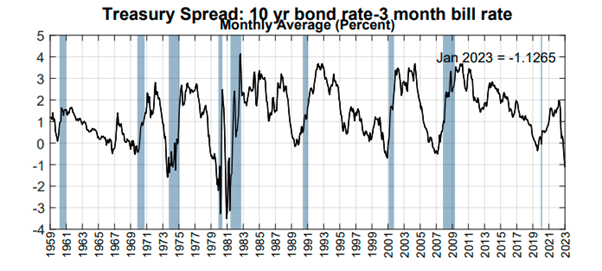

All the so-called ‘high frequency’ indicators of economic activity are signalling recession in the US economy. First, the bond yield curve remains inverted – I have explained before what this means as a reliable indicator of an impending recession. The inversion is now -80bp, which has not been seen since three months before the deep slump of 1981-2.

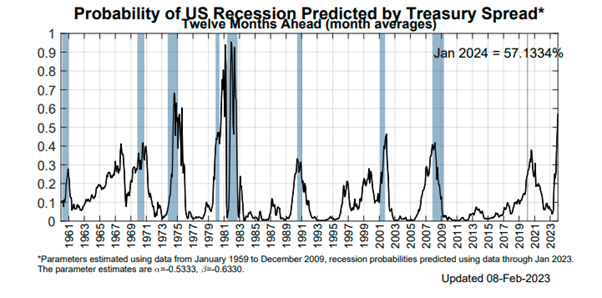

The New York Fed recession probability indicator stands at 57%, higher than before the Great Recession.

And the very pertinent Conference Board Leading Economic Index (LEI) recorded its 10th straight monthly decline – the longest streak of declines since the global financial crash of 2007-8. The trajectory of the US LEI continues to signal a recession over the next 12 months.

Maybe the major economies won’t go into a slump this year. But even if the stats don’t show a recession, it will feel like it for millions in the advanced capitalist economies and for the billions in the so-called Global South, when output growth slows to no more than 1% a year in the advanced economies and well below previous rates in the Global South, when employment stops improving and unemployment starts to rise, while inflation rates continue to outstrip wage growth.

From the blog of Michael Roberts. The original, with all charts and hyperlinks, can be found here.