By Michael Roberts

This article was originally published on 24 February 2023, the day before the Nigerian presidential elections, by Michael Roberts on his blog which can be found here.

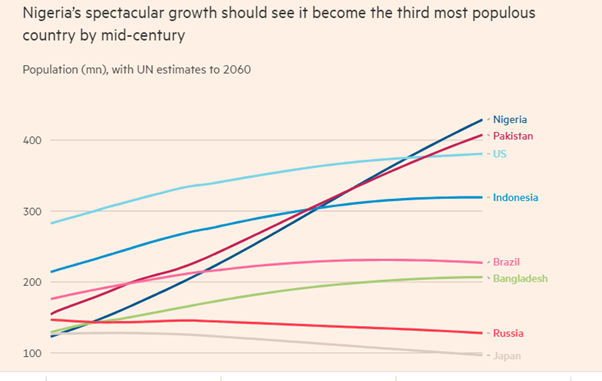

Tomorrow the people of the most populous country in Africa go to the polls to elect a new President. Nigeria is the biggest economy in Africa and home to at least 220m people. Its population will nearly double in the next 25 years to 400m, surpassing the US as the world’s third most populated country.

This is probably the most crucial election for Nigeria’s people for decades. The economy is stagnating, terrorism and crime is rife and threatens the daily security of the people – and successive governments have failed to meet these challenges.

The main presidential candidates

Normally, the election battle for the presidency is between two well-greased party machines. There is the ruling All Progressives Congress led by Bola Tinubu and the Tweedledum alternative is the People’s Democratic Party with Atiku Abubakar making his sixth attempt to become president. There are always a host of smaller parties which usually stand no chance because they lack funds or are just regional. But this time it seems there is a rising third party candidate, Peter Obi of the Labour Party. Certainly no socialist, Obi is a ‘businessman’ and former governor of a small eastern state and apparently a devout Catholic. But compared to the septuagenarian main candidates, Obi appeals to younger Nigerians, where the median age of the population is just 18 and 40% of 93m registered voters are below 35.

Obi leads in most opinion polls up to now. But his party is tiny and does not have enough people to cover the country’s nearly 177,000 polling stations to mitigate potential vote-rigging and other election-day tricks. So it’s unlikely that any candidate will win the necessary 25% of the vote in at least two-thirds of Nigeria’s 36 states plus Abuja, the capital, to win. So a second round may be necessary – something that has never happened before.

Daunting task due to poverty and insecurity

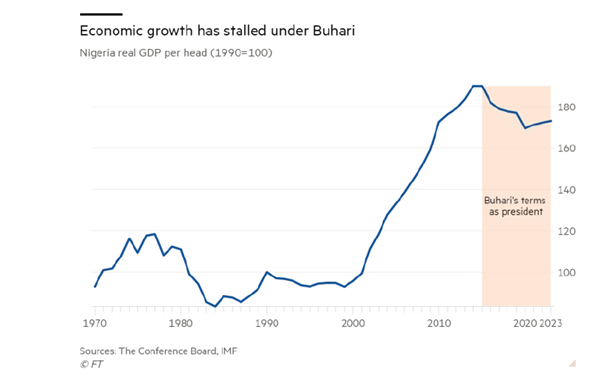

Whoever eventually becomes president faces a daunting task. Nigeria is close to being a ‘failed state’, despite the energy of its people. Under current president Buhari, income per capita has fallen and 90m Nigerians live on less than $1.90 a day. At least a third of the population are out of work and tens of millions hold precarious jobs in the so-called informal sector. At the same time, corruption among the elite is rife. To quote the IMF’s latest report on Nigeria: “Nigeria continues to experience large and petty corruption and weak enforcement of the rule of law with perception of corruption having worsened since 2016).”

Security is in an appalling state. During Buhari’s presidency, some 60,000 people have been killed by terrorists, criminal gangs or the army, according to data compiled by the Council on Foreign Relations. In the Islamic State of West Africa Province, an Isis offshoot, runs riot. And secessionist tendencies that erupted into a terrible civil war in the late 1960 are mounting. In 2022, Nigeria ranked 16th bottom out of 179 countries on the Global Fragile States Index and 143rd bottom out of 163 countries on the Global Peace Index. No wonder better-off Nigerians get out of the country if they can.

In 21st century, average real GDP growth was just 2.6%, barely matching population growth.

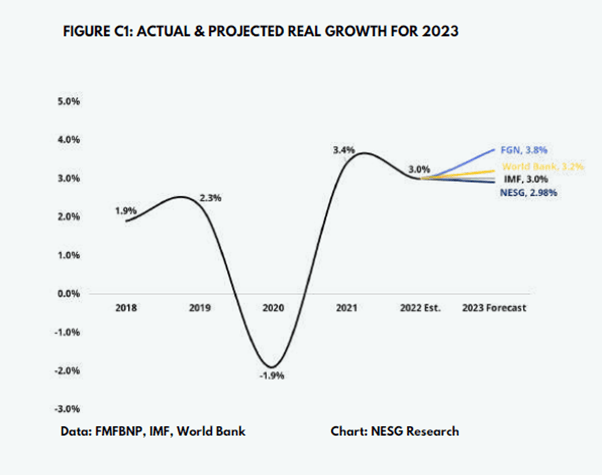

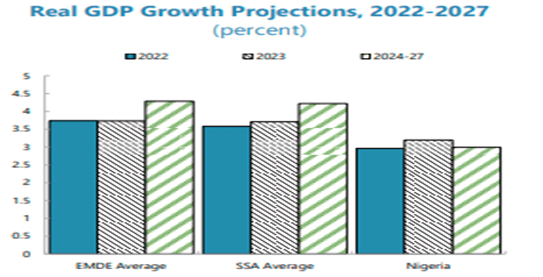

Nigeria’s GDP growth is projected at only 3% in 2023, with youth unemployment at 53% and a poverty ratio over 50%.

Indeed, the IMF’s growth projections for the rest of this decade are below the average for the Global South.

Nigeria relies on a few commodity exports to pay its external debts. Petroleum exports provide 80% of government revenue. But official production is below 1.3m barrels a day, well shy of Nigeria’s Opec quota, because so much is siphoned off illegally. Oil production is still 20% below the pre-pandemic level.

An alternative manufacturing base does not really exist and foreign investment has withered away.

With insufficient dollar revenues and a weak economy, Nigeria’s monetary authorities have resorted to printing money to fund government spending. And the rich don’t pay taxes. Nigeria has one of the lowest tax revenue-to-GDP ratios in the world, which makes its fiscal position vulnerable to shocks. General government revenue in Nigeria was 7.3% of GDP for 2021—less than half of the average in countries belonging to the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and nearly a third of the average of countries in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA)—and ranked as 191st out of 193 countries in the world! Almost all government revenues are swallowed up by debt service and payment of government salaries.

Inflation has rocketed to 22%. Just before the election the government replaced old currency in order to reduce fraud. The result was chaos with a run on the banks for cash – as most transactions are done with notes.

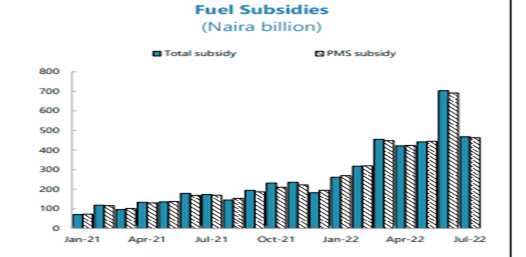

Pro-business policies are a threat to fuel subsidies

Both Obi and Abubakar are promising pro-business policies and a bigger role for the private sector. They aim to follow the usual international agency solutions for ‘growth’, namely ending fuel subsidies that people need to keep energy relatively cheap and ‘floating’ the currency. If these policies are applied, inflation will accelerate, especially for the poor.

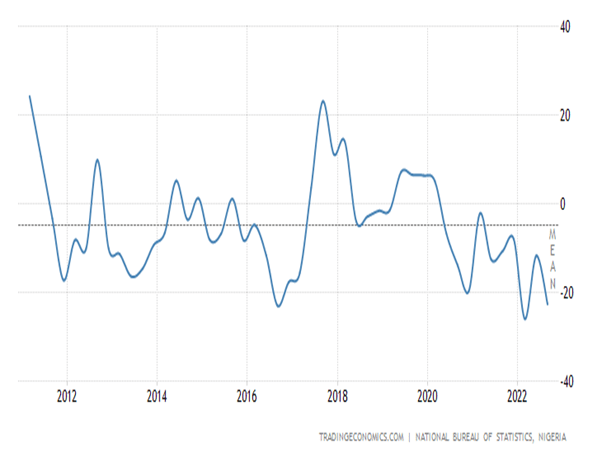

Productive investment has fallen as a share of GDP from 38% in 1999 to just 25% now. That has been driven by a very low profitability for capital, except for the brief period of the oil price boom between 2000 and 2007.

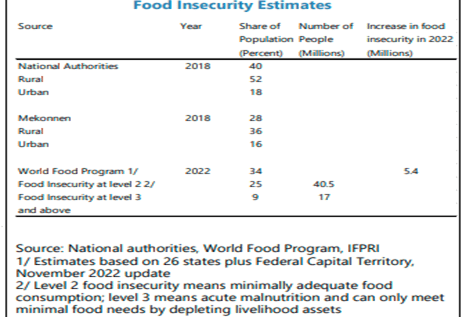

The country is endowed with immense agricultural resources and over 81m arable and largely fertile hectares, with maize, cassava, guinea corn, yam beans, millet, and rice being the major crops. Despite that, Nigeria is among the least food secure countries. Using the September 2018 to October 2019 household survey of expenditures, the cost of achieving 2,251 calories per day (age-weighted caloric need for food security), is about 82,000 naira per person per year. Based on this survey, about 40% of the Nigerian population is identified as ‘food insecure’ (IMF).

Food insecurity affecting millions

Data from the World Food Program shows a significant increase in its estimate of acute malnutrition for 2022, likely reflecting the effects of soaring food prices and security concerns, with an additional 5.4m people estimated to have become food insecure since 2021. The increased food insecurity is particularly relevant in the north-east states of Borno, Yobe and Adamawa, where the population is severely undernourished across many indicators.

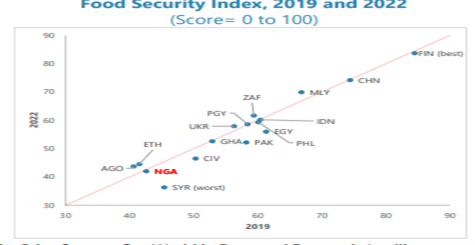

Indeed, rich Nigeria has one of the lowest scores for food security in the world.

More than 10m children are out of school, two-thirds of them girls. Universities are unable to pay lecturers properly or maintain buildings. The average school drop-out rate stood at 33.7 percent, far above the global average of 8.5 percent.

Average life expectancy is just 53 years

Health provision is poor, with Nigeria’s elite relying on foreign hospitals. Nigeria ranked 170th out of 194 countries on the WHO’s global universal health service coverage index in 2019. In addition, Nigeria ranked 187th out of 195 countries on the Health Access Quality (HAQ) index in 2018. The index measures the quality and accessibility of healthcare based on 32 causes of medically preventable death. Out-of-pocket spending accounted for 70.% of current healthcare spending in 2019, higher than the global average and sub-Saharan average of 29% and 18%, respectively. The National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) has only covered about 5% of Nigerians.

At 53, Nigeria’s life expectancy is shockingly low, a decade below Ghana’s, a country with a similar income per capita. According to the World Bank, the country’s Human Capital Index (HCI) stood at just 0.36 in 2020, slightly above 2018’s 0.35, thereby positioning the country among the bottom ten countries with the lowest HCI globally.

Capitalism has failed Nigeria.

From the blog of Michael Roberts. The original, with all charts and hyperlinks, can be found here.