The wall-to-wall coverage of the Coronation over last weekend masked what was a disastrous round of local elections for the Tory Party, losing over a thousand council seats. But the results also contain some significant warnings for the Labour leadership, not that they will take any notice.

Before the elections, a Tory damage limitation exercise was already in full swing. Attempting to manage the expected fallout, Tory spokespersons suggested they would lose a thousand seats, thinking they could therefore find some comfort when the results actually turned out better. But in the event, the final results produced even greater losses than their ‘worst case’ scenario.

Suffering the worst cuts in living standards for generations, while the rich get richer, struggling to pay for energy bills while big energy companies make record profits, with millions having to go on strike just for their wages to keep up with rising prices – these were the factors that made the Tory vote collapse to around a quarter of the total.

Whatever the detail in the political pundits’ analysis, the overarching lesson is the profound unpopularity of the Tory government. The Tories’ new voter suppression policies – the introduction of ID for polling – may even have minimised the impact, because many of those without ID would have been Labour voters. But the general trend was still clear.

Projected national Labour lead of only 9%

It is necessary to add some caveats to any conclusions one might draw from Thursday’s voting. Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland and many English councils (and London boroughs) had no elections. But taking this into account, with the poor turnout – always lower in local compared to general elections – the BBC nevertheless projected a national result that would have seen the Tories on 26% of the vote and Labour on 35%.

Put another way, the Tories have been able to inspire only around an eighth to a tenth of the population who could have voted to turn out for them. The BBC reported the polling expert, John Curtice, describing the results as “only a little short of calamitous for the Conservatives“.

The Tories lost more than a thousand seats and control of 48 councils, many of them in their former Tory heartlands in the South of England, like Hertsmere and Brentwood. Tory recriminations are already beginning. In Swindon, for example, where Labour took control for the first time in twenty years, the deposed Tory council leader blamed “the cost of living and the performance of the government in the last 12 months.” He’s not wrong there. “I think we can safely say“, said a former Tory councillor who lost his seat in Plymouth, “that the Conservatives will lose the next general election”.

It goes without saying that working people will be happy and relieved to see the Labour Party win 22 councils – many straight from the Tories. Places like Swindon, Amber Valley and Erewash in Derbyshire, Plymouth, Medway, Gillingham, and Bracknell Forest. They will have expectations that Labour councils will act in their interests far better than the Tory versions. We can all be equally cheered by the virtual collapse of the successor party to UKIP, Reform UK, (including its surrogates standing as ‘independents’) where they stood.

Labour spokespersons have been quick to repeat the claim that Labour is “on course” to win a majority in the next general election. That may be true – Labour having a nine-point lead, if these results are taken as an opinion poll – but the significantly increased votes for the Lib-Dems and the Green Party are a warning to Labour. A general election victory, certainly an overall majority, is not a foregone conclusion.

Green Party alone made gains approaching half of Labour’s

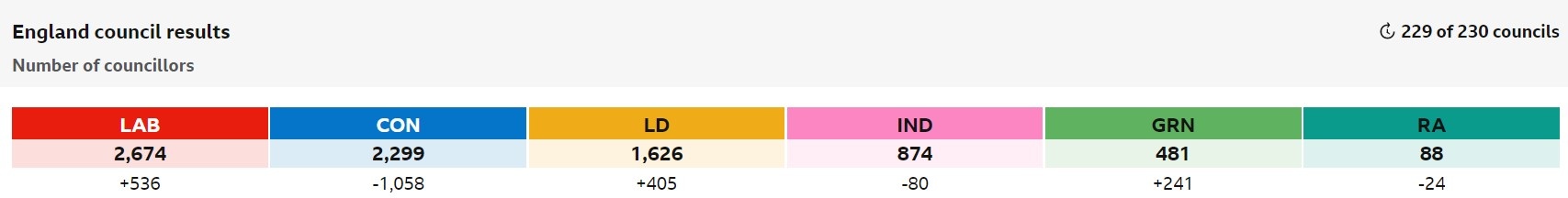

Labour might now be the largest party in local government for the first time in over twenty years, having gained 536 seats. But between them, the Lib-Dems and Greens won over a hundred more seats than Labour did, at 646. The Green Party alone gained 241, approaching half the number gained by Labour.

There might have been some reaction among Tory voters to environmental issues, such as the discharge of thousands of tonnes of raw sewage into rivers and streams, which has become such a national scandal that even the Tory press cannot hide.

But in the majority of cases, the increased vote for the Greens has been simply because they are perceived to be to the left of the Labour Party. A number of successful Green candidates, in fact, were former Labour members and councillors who had been hounded out of the Party by the Tory-lite faction that controls the Party apparatus and leadership.

There were also notable gains for independent left candidates who had been forced out of the Party. In Orrell Park, Liverpool, Alan Gibbons, the sitting councillor, won as an independent, with nearly 77% of the vote, where Labour failed to get even 20%. Two other Labour expellees, Sam Gorst and Lucy Williams, were also elected as independents in Liverpool.

In Bromborough, Wirral, Jo Bird, another Labour expellee, was elected top of the poll as one of three Green Party candidates. In Portsmouth, the left-wing former council leader, Cal Corkery, who had also been expelled, stood as an independent and also won. All of these former Labour members were treated appallingly by the Party apparatus, one of them, Jo Bird, having even been elected by Labour members to the NEC, only to be manoeuvred out on some spurious pretext.

Another commitment abandoned by Starmer

The Green Party saw the biggest advance in its 50-year history, winning control of a council – Mid-Suffolk – and becoming the largest party in Lewes, where the Tories were wiped out. Starmer’s decision to abandon the previous policy of abolishing university tuition fees days before the poll was almost tailor-made to put off younger voters. According to the Guardian two days after the polls, Labour’s vote is down in areas with the highest number of graduates, “losing ground to the Greens.”

It is understandable that many voters disillusioned with Starmer’s Labour Party should vote Green, seeing it as a more ‘radical’ alternative and socialists will have some sympathy with that view. The Greens website was correct in arguing that their party was gaining “from a deep dislike of the Tories and Starmer’s uninspiring Labour”.

On environmental issues, the Green Party is more consistently to the left of Labour. They may even support the public ownership of energy companies, although that is not clear. But in the long run, they will be judged, not by their appearance, which is ‘radical’, but by the whole range of social and economic issues.

Do they support socialist policies in relation to the economy as a whole, or are they content to base their programme and perspective on the continuation of the market system? Do they support workers’ strikes in defence of living standards? As much as the tradition of struggle embodied in the broader labour movement is entirely foreign to the cabal around Keir Starmer, it is also largely unknown territory to many of the Green Party.

Starmer’s main policy is not being Corbyn

Be that as it may, the gains for the Lib-Dems and the Green Party sound a warning to Starmer’s Labour Party. His Tory-lite policies are indeed utterly uninspiring. In so far as Labour gained seats, it has been entirely as a result of a growing alienation of voters from the Tory government. Even then, a lot of Tories preferred to abstain or vote Lib-Dem rather than turn to Labour.

There are also warning signs in the fact that Labour lost council positions in places where they ought not to have done, like in Slough and Peterborough. To lose 22 seats in Leicester is a disgrace and it is the direct result of the mass banning of sitting Labour councillors, preventing them from standing in that city by the right-wing.

The detailed picture, therefore, shows that Starmer’s only certain policy – “not being Jeremy Corbyn” – is a failure. At a projected 35% of the vote, Labour is no better off than it was a year ago, despite the desperate squeeze on living standards.

On the balance of probabilities, Labour seems destined by these results to win the next general election. But two things are also clear. The first is that there is no guarantee that Labour will win an outright majority, as the national lead over the Tories seems to be thinning. The second is that once in office, Labour may face a more serious haemorrhage of support to the Greens than was previously expected.

Twice, the right-wing Labour leader Neil Kinnock managed to snatch a general election defeat from the jaws of victory, in 1987 and 1992, not least because he was obsessed with purging his own left wing. It may not be the most likely of probabilities, but it cannot be ruled out that Starmer’s Tory-lite approach could do the same in 2024.