By Michael Roberts

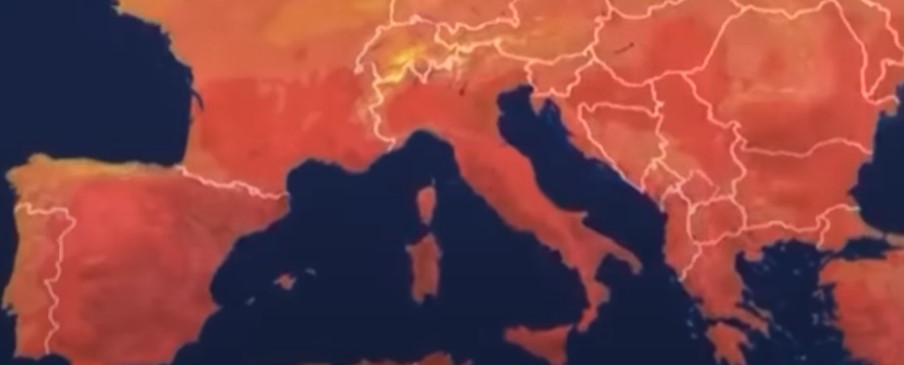

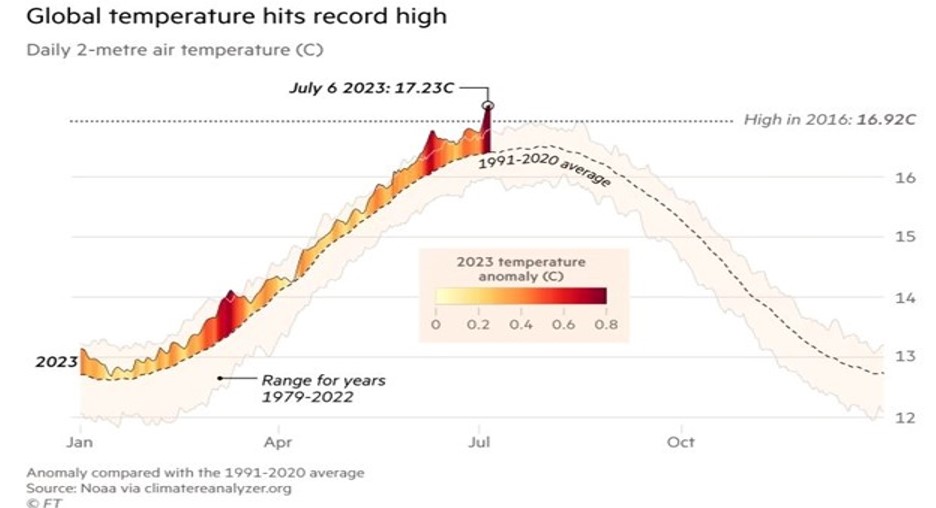

As I fry in record temperatures in the south of France, the concept of a short sunny vacation away from the vagaries of British weather has evaporated. The world endured the hottest week ever recorded between 3-10 July this year. And meteorologists say there is more to come – a lot more; indeed, a new global temperature record is still likely to be set before the end of next year.

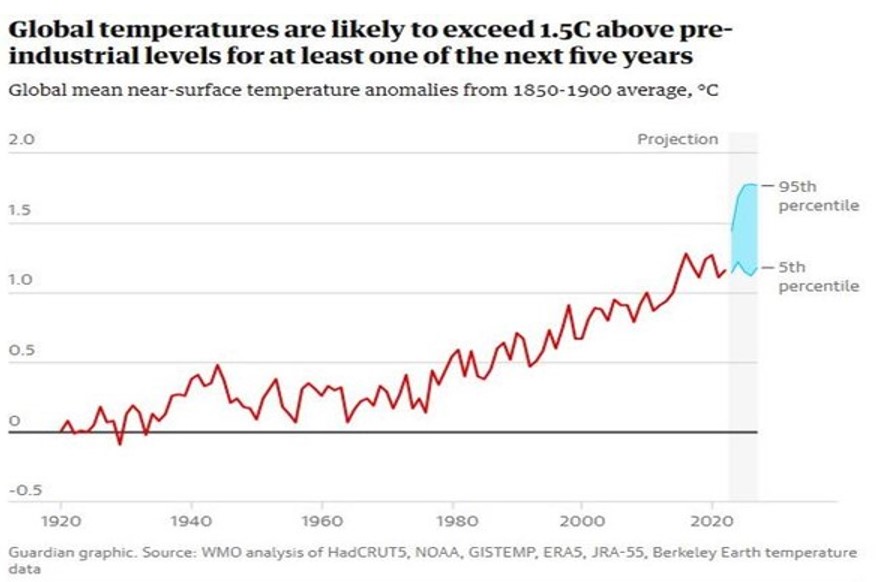

As a result, there are forecasts that this year or next could see world temperatures pass the 1.5C threshold that was set by the IPCC as being the upper limit for a rise in global warming that would avoid the planet passing through meteorological ‘tipping points’ that could bring irreversible changes to world weather patterns. Already last year, more than 61,000 people are estimated to have died prematurely as a result of the soaring temperatures that gripped Europe last summer.

The world is almost certain to experience new record temperatures in the next five years, and temperatures are likely to rise by more than 1.5C above pre-industrial levels. The World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) found there was a 66% likelihood of exceeding the 1.5C threshold in at least one year between 2023 and 2027.

Changing rainfall patterns causing flooding

Climate change is driving ever more extreme weather events, including changing rainfall patterns that caused fatal flooding in the US, South Korea, India and Japan over the past week at the same time as an extreme heatwave called Cerberus is forecast for southern Europe. These extreme weather events are another indication, together with stunningly hot ocean temperatures, dangerous heatwaves, and the rapid loss of polar icesheets, that fossil fuel production and use is massively disrupting the planet’s climate.

The 2021 landmark UN IPCC report signed off by 270 scientists from 67 countries around the world found that global warming would trigger changes to wetness and dryness, winds, snow and ice. Along with more intense rainfall and flooding in some areas, some regions would experience more intense drought. Precipitation is more likely to increase in high latitudes, while changes to monsoon precipitation are expected, the IPCC report said.

“What climate change is doing is supercharging weather events,” said Rachel Cleetus of the Union of Concerned Scientists. “Where there are dry periods, you are now getting megadroughts. This cycle is also very dangerous, because when you get very dry land that is denuded of vegetation, then when you get the rainfall you get mudslides.” She added: “I want to emphasise that this is human-caused climate change and this is happening because of the burning of fossil fuels.”

The immediate heat wave is a drastic combination of global warming and the arrival of El Nino, the warm phase of the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and is associated with a band of warm ocean water that develops in the central and east-central equatorial Pacific. The ENSO is the cycle of warm and cold sea surface temperature (SST) of the tropical central and eastern Pacific Ocean. El Niño is accompanied by high air pressure in the western Pacific and low air pressure in the eastern Pacific. El Niño phases are known to last close to four years; however, records demonstrate that the cycles have lasted between two and seven years. Temperatures in the Pacific are then warmer than normal –by rising about 0.2C during El Niño. Together, carbon emissions and El Nino are creating accelerated temperatures in the northern hemisphere with all its consequences.

Temperatures rising faster than expected

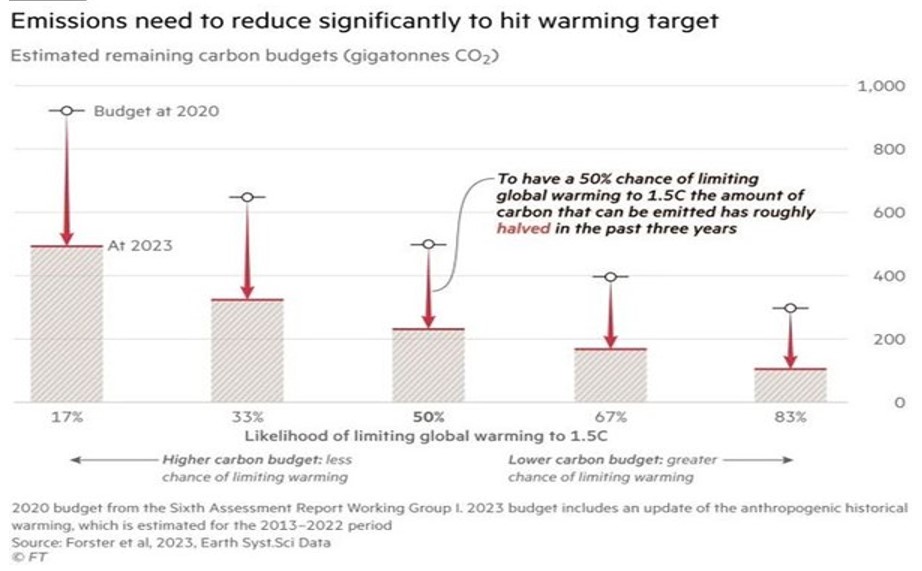

Indeed, the world’s remaining “carbon budget”, or the amount of carbon dioxide that can be emitted to have a 50 per cent chance of limiting global warming to 1.5C, has halved in the past three years, a group of leading climate scientists have calculated. That budget would be exhausted in less than six years at current emissions levels from energy of about 38bn tonnes a year, as a result of the continued pollution and taking into account the latest data showing temperatures were rising faster than expected, they said. “This is the critical decade for climate change,” said Piers Forster, director of the Priestley Centre for Climate Futures at the University of Leeds.

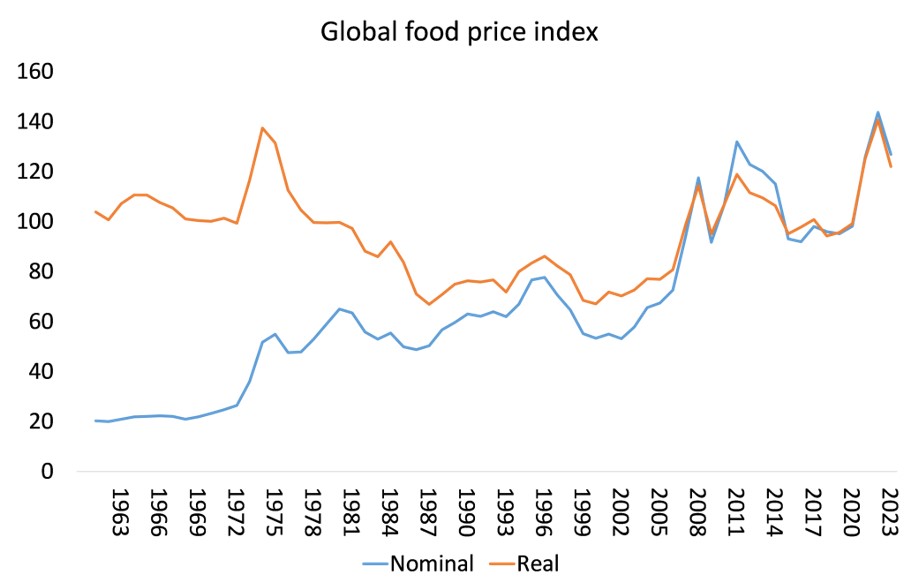

The longer-term impact will be on food security too. Since the COVID pandemic, global food prices hit new highs. Prices have fallen back a little since but now the damage to grain yields and other key food products from excessive temperatures is likely to drive prices up again.

The number of people affected by hunger globally rose to as many as 828 million in 2021, an increase of about 46 million since 2020 and 150 million since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a United Nations report that provides fresh evidence that the world is moving further away from its goal of ending hunger, food insecurity and malnutrition in all its forms by 2030.

Carbon emissions continue to rise

After remaining relatively unchanged since 2015, the proportion of people affected by hunger jumped in 2020 and continued to rise in 2021, to 9.8 percent of the world population. This compares with 8 percent in 2019 and 9.3 percent in 2020. Around 2.3 billion people in the world (29.3 percent) were moderately or severely food insecure in 2021 – 350 million more compared to before the outbreak of the COVID‑19 pandemic. Nearly 924 million people (11.7 percent of the global population) faced food insecurity at severe levels, an increase of 207 million in two years.

Emissions must be cut by almost half by 2030 to limit the temperature rise to the1.5C level at which irreversible planetary changes are expected. But they continue to rise annually instead. Carlo Buontempo, director of Copernicus said: “We haven’t seen anything like this in our history. And for me this is a tangible example of what it means to be working in uncharted territory. Climate change is not something that is going to happen in 20 or 30 years’ time, it is happening now.” Sumant Sinha, head of India’s ReNew Power said of the Paris 1.5C target limit for global warming, “You can pretty much bury that target,” And even 2C is “looking a bit dicey”.

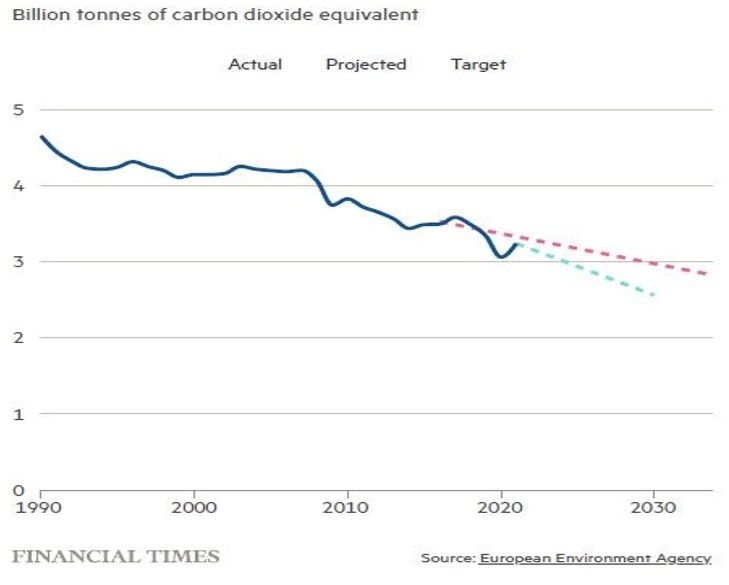

Europe is not meeting its climate mitigation targets. The European Climate Neutrality Observatory calculates that by 2021, the EU had cut its emissions by 30 per cent compared with 1990 levels. But to reach the 2030 goal it would need to make further cuts of 132 mega tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent a year, roughly the annual output of 332 gas-powered stations. https://www.ecologic.eu/19314

“The past five years of data offers a clear message: while emissions in Europe have continued to go down, a faster rate of reduction is required to meet both the 2030 target and climate neutrality by 2050,” it added. The World Meteorological Organization said this week that Europe was warming, with temperatures around 2.3C above pre-industrial levels in 2022. Fossil fuel subsidies are supposed to be phased out by 2025, but have increased over the past five years.

Energy firms have made record profits by increasing production of oil and gas, far from their promises of rolling back emissions. Exxon’s CEO, Darren Woods, told an industry conference last month that his company plans to double the amount of oil produced from its US shale holdings within the next five years. Wael Sawan, CEO of Shell, said curbing oil and gas production would be “dangerous and irresponsible”. “The reality is, the energy system of today continues to desperately need oil and gas. And before we are able to let go of that, we need to make sure that we have developed the energy systems of the future – and we are not yet, collectively ,moving at the pace [required for] that to happen.” Indeed!

COP28, the next UN summit on global warming, is being hosted by United Arab Emirates (UAE) who appointed oil executive, Sultan al-Jaber as president! The appointment was “a scandal” and a “perfect example of a conflict of interest,”says Michael Bloss, a German member of the European parliament with the Green Party. “It’s like putting the tobacco industry in charge of ending smoking.”

Meanwhile, Europe and many other parts of northern hemisphere fry. And the poorest parts of the world, already experiencing greater poverty from COVID and rocketing food and energy prices, will suffer even more, with many areas on the planet becoming uninhabitable for humans – other species have already been wiped out.

This is from the blog of Michael Roberts. The original can be found here.