By Roger Silverman

[Editorial note: Fifty years ago this month, on September 11, 1973, a military coup took place in Chile, putting a committee (‘junta’) of generals in power, led by General Pinochet. The coup resulted in the bombing of the presidential palace and the subsequent murder of the president, Salvador Allende. Allende’s government had been a left “Popular Unity” government, committed to reforms in the interests of workers and the overthrow was instigated by the Chilean and international capitalist class.

This article by Roger Silverman, was published in the Militant International Review in January 1974. It gives a powerful description not only of the events that led up to the coup itself, but also points to the lessons that socialists need to learn from it. Parts TWO and THREE of the article will be published later]

……………………………………………………………………………………………..

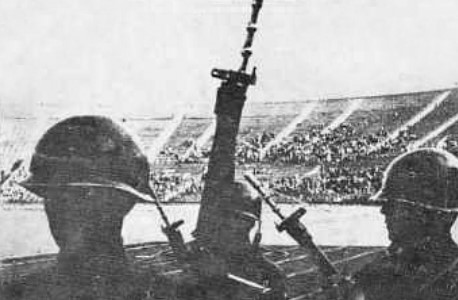

The counter-revolution in Chile is in full blast. Thousands of workers have died under its blow. An American doctor in Santiago has estimated that up to 25,000 Chileans have been executed. Two American students, who were imprisoned in the National Stadium in Santiago – where even the Junta is holding 7,000 prisoners – saw with their own eyes the shooting of 400 to 500 prisoners in groups of 30 to 40. A Mexican diplomat has asserted that the regime has a blacklist of 13,115 foreigners to be systematically wiped out – mostly political exiles from Bolivia, Brazil, Uruguay and other Latin American states. Sickening descriptions have been given by eye-witnesses of sadistic beatings and tortures.

In the whole violent history of the South American continent, the classical home of military coups, this undoubtedly the bloodiest upheaval in more than fifty years. It is a massacre almost on the scale of the Indonesia bloodbath of 1965, where, as in Chile, an enraged officer class avenged itself of the workers’ organisations after overthrowing a government which tried to lean on the support of the working class. The Junta has surrounded mines and factories with tanks, and decreed that workers must work on Saturdays and on two public holidays without extra pay. This is reaction at its ugliest. All the hopes of the oppressed masses lie in ruins under the iron heel of a military dictatorship. A cruel less is being given to the workers and poor peasants of the whole teeming continent.

The Junta itself estimates that as many as 15% of the workforce have been sacked as ‘militants’ and ‘agitators’. These workers are starving and destitute, unable to get new jobs, forced into vagrancy and crime. The Junta has sworn to ‘stamp out Marxism in Chile. How many times before have we heard this threat? The generals will find that they cannot order the class struggle to stop. History cannot be pushed backwards. Marxism has been prematurely buried over and over again, under the general’s gun, the professor’s textbook, or the traitor’s lie; but it returns again every time with redoubled force, because Marxism alone corresponds to modern social reality.

Loyal servants to ruling class

The generals, as loyal servants to the ruling class, have announced that the ‘immense majority’ of companies nationalised by the ‘Popular Unity’ government are to be returned to their former owners. Pinochet, Leigh and the other leaders of the Junta have Fascist ambitions. They have vowed to crush Marxism and they have shown unrelenting savagery in their violent war on the workers’ parties and trade unions.

But they have seized power without any solid social basis. They do not have the organised paramilitary force of demented small businessman, bankrupts, former officers and thugs, that made up Mussolini’s Fascisti, Hitlers’s SA and SS or Franco’s Falange. There is a small “Gremialist” movement, based largely on the Catholic University, which stands for the replacement of trade unions by guilds (‘gremios’) containing both workers and employers, and the other paraphernalia of a corporate state.

But the Gremialists and the “Patria y Libertad” do not provide the basis for a Fascist regime which can roll back history even for a couple of decades. Most of the politicians from the orthodox right-wing parties are pressing the regime to set up and equivalent to the Arena, the civilian party which give a parliamentary façade to the Brazilian junta. But it will remain an unstable military dictatorship, a regime of crisis.

A regime resting on nothing but its own police and army is always precarious, no matter how brutal it might be. The Argentine generals and the Greek Colonels have discovered that. The Chilean coup is similar to the reaction following the defeat of the Asturian Commune in 1934 [in Spain], which killed 30,000 workers. Only two years later, the revolution leapt forward once again.

The workers of Chile will have the last word, and this bitter blow will harden their resolve to carry the revolution through to a conclusion. But the lessons of the Chilean coup extend far beyond Chile’s borders. Allende’s election in 1970 was hailed as a model of peaceful change for workers everywhere. This was to be the living refutation of those ‘romantics’ and ‘ultra-lefts’ who ruled out the possibility of a gradual and constitutional transition to socialism. It was also, if not quite logically, asserted in the same breath, that such a change was all the more possible in Chile, because of the unique tradition of parliamentary democracy, respect for the constitution, the neutrality of the armed forces, etc.

An ’imperialist’ plot?

Allende defended “the Chilean road” because “though it is the most difficult, it is the best and carries with it the fewest risks in human terms.” His speeches make gruesome reading today, as the thousands of corpses in Chile’s mass graves pile on top of the junta’s first victim – Salvador Allende.

Why did the “Chilean experiment” fail? The Morning Star blamed “the plots of imperialism and the CIA.” John Gollan, Secretary of the British Communist Party (Morning Star, September 15, 1973), wrote, “Nixon and the Pentagon are in the thick of this vile crime.” Tony Chater, another CP leader (Comment, October 6, 1973) called the coup “a brutal act of imperialist aggression” and listed the evidence of American involvement.

Certainly, the hands of US imperialism are deeply stained with Chilean blood. To take the most scandalous example, a letter was unearthed from Hal Hendrix (head of the private Latin American intelligence service of the multi-national corporation, ITT), to a colleague, in which he talked of General Viaux’s plans to launch a coup to prevent Allende taking office: “Rumour that (Viaux) would trigger a coup on October 9 or 10 were rampant…Word was passed to Viaux from Washington to hold back last week. It was felt that the was not adequately prepared, his timing was off, and he should cool it for a later, unspecified date…as part of the persuasion to delay, Viaux was given oral assurance that he would receive material assistance and support from the US and others for a later manoeuvre.”

There was plenty of other evidence. The Observer provided evidence of connections between the Fascist “Patria y Libertad” organisation, the big industrialists’ association and two CIA agents in the copper miners’ strikes. The Chilean paratroop regiment were trained in the USA. The State Department admitted having prior knowledge of the coup, and the same day, US warships lay off Valparaiso, for “joint naval manoeuvres”. Neither is there any secret about the cutting off of all loans and credits from 1971 onwards, and the speedy resumption of aid after the coup.

But what was to be expected? American capitalists had lucrative stakes in Chile. After an initial investment of $50-80million, 44 years ago, the copper mine owners alone have raked in a cool $4,000million profit, according to Allende. These were the first enterprises to be nationalised by Allende’s government. To expect the military espionage monster of US imperialism to roll over and play dead is as naïve as to call the recognition of the new regime by British capitalism “the stench of betrayal”, as Gollan did. For capitalists to show solidarity against world revolution is no “betrayal”!

History does not unfold through conspiracies

Certain reactionaries always explain strikes by the presence of “Communist agitators”. In the same way, some sections of the left think that once they have discovered the hand “American imperialist aggression”, there is nothing more to be said. History unfolds not fundamentally through “plots” and “conspiracies”, but through the class struggle. The hand of American imperialism was not an unseen and accidental intervention from outside, but the major obstacle in the path of the Chilean revolution. It is no explanation to say: the revolution was just getting along nicely, when the ruling class came along and spoiled it. If the ruling class were not hell-bent on hanging on to its power, no matter what the cost in workers’ lives, then the Socialist revolution would be not only easy, but unnecessary.

From 1918 to 1921, the Russian workers and poor peasants had to stand up, not just to hidden sabotage and undercover aid to the White Guards, but the direct military intervention of no less than 21 imperialist armies! How did the Bolsheviks respond to this? With complaints at the “unsporting behaviour” of world imperialism? On the contrary, they replied with the implacable arguments of armed resistance linked to bold internationalist propaganda. Faced with an armed people, a militia of ragged workers and peasants ready to fight with their bare fists if need be to defend their revolution, the troops of the intervention melted away.

The soldiers and sailors became infected with revolution. Mutinies and desertions were rampant. Industrial action by the workers in Western Europe, electrified alike by the power of their Russian brothers, forced world capitalism to retreat. The world revolution emerged enormously strengthened by the courage and skill of the Bolsheviks in the teeth of reaction.

How much flimsier was the challenge facing the leadership of the Chilean workers? American imperialism dared not intervene directly. The days of Panama, Guatemala and Santo Domingo are over. The humiliating defeat in Vietnam, the scramble from South East Asia, the weakness of the dollar, the degradation of the White House, and the explosive mood all over Latin America, all made military invasion of Chile unthinkable for the American ruling class.

The Chilean workers fought heroically, ready to sacrifice their lives under the tanks, planes and firing squads of the hated junta. For the very beginning, they had rallied loyally to the support of the Popular Unity government. They have earned an honoured place in the long scroll of martyrs for Socialism. Either Socialism itself is just a sentimental dream – or the energies of the workers were needlessly squandered. Any Socialist must conclude that the workers’ leaders failed to harness the masses’ power; that their false programme delivered them into the bloody hands of their executioners.

Allende’s government carried through a programme of reform within the confines of capitalism, hardly equalled in history. Copper, coal, nitrates, steel, cement, telephones, tyres, textiles, banking, fishing, were all either totally or partially nationalised. In the first year, industrial production rose by 13%. About nine million acres of the biggest landed estates were distributed to the poor peasants. Great social reforms were achieved, raising the living standards of some workers by 20%. Children were given free milk and meals at school. Great strides forward were taken in the fields of pensions, welfare services, health, housing and education. The poor supported with growing enthusiasm what they saw as “their” government.

What was the “Popular Unity”?

To understand how their hopes were so cruelly dashed, it is necessary to examine exactly to what extent it was “their” government. What was the “Popular Unity”? It was an electoral bloc which tied the two mass workers’ parties, the Communists and, to their left, the Socialists – both nominally Marxist-Leninist parties – together with the Radicals and five small liberal splinter groups.

These [latter] six parties stood for reforms within the framework of capitalism and their main function was to act as watchmen over the workers’ parties, millstones around their necks, to hold them back from taking full revolutionary measures against capitalism. It was hence a coalition of conflicting interests, an unprincipled bloc. Allende thought that by “uniting” this assortment of mutually incompatible parties around a minimum programme which represented the lowest common denominator, he could unite their supporters into a solidly welded monolithic movement for gradual change.

The “Popular Unity” government therefore proclaimed its intention not to proceed immediately to socialist policies, but to complete first the “anti-oligarchic and anti-imperialist” revolution, and then to “open the road” to socialism sometime in the future. While carrying through sweeping reforms, it also tried to contain the spontaneous movement of the workers and poor peasants to take over the factories and landed estates.

Every party was thrown into internal convulsions by the upheavals of the three years of the “Popular Unity” government. One wing of the Christian Democratic Party split off to form the MAPU, which entered the alliance and gravitated rapidly towards the left. Later, there was a further split and the IC (Christian Left) also broke away to support the “Popular Unity”. The original leaders of the MAPU, uneasy about that party’s radicalization, left MAPU to join this new formation.

These successive defections from the Christian Democratic Party obviously left that party more firmly under the control of its right wing leadership under Frei and Alwyn, which emphasises still further Allende’s folly in trying to appease the Christian Democrats to the bitter end. The Radical Party too was swept leftwards. At its Congress in July 1971, it passed a resolution accepting “historical materialism and the class struggle” and calling for “the abolition of private property in the means of production.”

This in turn provoked the right wing to break away and form the misnamed Radical Left Party (PIR). Even within the Communist Party, a certain polarisation was beginning to take place in the last days of the Allende government and an opposition to Corvolan crystallised around Jorge Insunza. But the Socialist Party above all became the arena for bitter political struggle. The right-wing around Briones was ejected and the General Secretary, Carlos Altamarino, became the focal point for a strong left wing, which maintained a vigilant and critical stance in relation to Allende. Both the Santiago branch of the Party and the Young Socialists called on the leadership to set up a workers’ militia, and it was these sections which played the main role in importing arms into the factories.

If a clear, conscious Marxist cadre had existed within the Socialist Party, it would have become the nucleus for a mass revolutionary tendency in the stormy events from 1970 onwards. A Bolshevik Party could have been created, capable of articulating the instinctive movement of the working class for power, and of carrying revolution through to a successful conclusion. The Movimiento de Izquierdia Revolucionaria (Movement of the Revolutionary Left) was a tendency based mainly on students, who isolated themselves from the workers’ organisations. Here and there they successfully encouraged occupations of landed estates and in some cases of factories, but they based their tactics on “single combat” with the representatives of state power. The sporadic occupations were never linked to the overall perspective of mobilizing the working masses to take power.

Popular Unity similar to Kerensky regime in Russia

It was this tendency that was founded by self-styled “Trotskyists” who, here as elsewhere, hoped to build a revolutionary movement while bypassing the existing traditional organisations of the most conscious strata of the working class. They sought to mobilise the most backward layers of society, the poor peasanty or the lumpenproletarian (or semi-proletarian) elements in the shanty towns encircling Santiago. Their exploits in seizing certain medium-sized estates made no impact on the political consciousness of the activists within the workers’ parties.

It was only at the end of 1972 that a “regroupment” of some of these grouplets took place, and a new party was founded, once again in isolation from the mass organisations – the “Revolutionary Socialist Party”. It is a tragic fact about the Chilean events that those revolutionary elements to the left of the mass parties impatiently followed adventuristic policies of creating “armed combat organisations” to shoot it out with the incomparably mightier repressive apparatus of the state machine, instead of adopting the method of Lenin in April 1917 – only six months before the world’s first socialist revolution! – and pursuing a relentless and meticulous policy of “patient explanation” to raise the consciousness of the workers to a sense of their own innate power.

The “Popular Unity” government was similar in composition to the Kerensky regime in Russia, after the direct representatives of the capitalists had been forced out of the coalition. The workers’ parties gave permanent right of veto, not only to the Radicals and the other reformist parties inside the coalition, but above all to the Christian Democrat opposition, on whose votes in Congress the government depended. This was the real character of the government led by what the Press called “the world’s first democratically elected Marxist President.”

In reality, the Chilean “experiment” was nothing new. Didn’t the Russian Mensheviks in 1917 also patch up a coalition government with the peasant Social-Revolutionary Party, and even, while they could, with the Cadets, the capitalist party, on the grounds that it was necessary to secure the maximum “popular unity” in defence of the “anti-oligarchic and anti-imperialist” February Revolution? And what about the “Popular Front” government in Spain, which brought the parties at the head of the revolutionary working class into a coalition with the “shadow of the capitalists”, the abandoned relics of the old liberal parties of a ruling class that had already fled to the Fascist camp? That too was justified by the need to “unite the forces of democracy” against Franco.