Cain O’Mahony presents a detailed account of a largely forgotten socialist uprising – airbrushed from history by both “the west” and the Stalinists.

***

History is written by the victors. That is why the Slovakian National Uprising of 1944 during World War II has been pushed to the back shelves.

It was not so much an uprising as a revolution, out of control of either the Western Allies or the Soviet Union. It demonstrated what could have happened during the revolutionary wave that swept Europe with the fall of Nazi Germany, had such movements not been supressed by the Western Allies or derailed by the Stalinists.

Following Hitler’s annexation of Austria in 1938, it was inevitable that Czechoslovakia would be next, as this independent country pointed like an accusing finger into the heart of the new ‘Greater Reich’.

“Munich” betrayal and general strike

The betrayal of Czechoslovakia came with the Munich Agreement of 1938, when both British and French Imperialism – both looking for appeasement of Hitler and hopeful of pushing Nazi Germany into war with the Soviet Union – abandoned the Czechs and left them to their fate. As Trotsky commented: “England and France threw Czechoslovakia into Hitler’s maw to give him something to digest for a time…” (A Fresh Lesson: on the Character of the Coming War, 1938).

In Prague, when news of the Munich betrayal broke, there was a spontaneous General Strike and mass protests: “Without any call, without any leadership, the workers, in spite of marshal law and the prohibition of meetings, went on a complete General Strike and marched in tremendous masses into the heart of Prague. The police disappeared, the soldiers were kept in their barracks to prevent fraternisation with the demonstrators” (Joseph Guttman, The National Question in Central Europe, 1939).

But the spontaneous movement was leaderless. The Czechoslovakia President, Edvard Benes, representing the Czech bourgeoisie, resigned saying he had ‘failed the people’, but in reality, was using the mass protest as an excuse to flee to France and then London, to set up a ‘government-in-exile’. In effect, the Czech bourgeoisie just walked away.

Neither was there much initial leadership from the workers’ parties, now being driven underground. The Czech Social Democratic Party formed the ‘P.V.V.Z’ – ‘We Remain Faithful’. But faithful to what? It was to Benes and the government in exile, who the masses knew had just walked out on them.

The Czechoslovakian Communist Party, the KSC, were in an even more hidebound position. They were slavishly tied to the ‘party line’ from Moscow, like all Communist Parties around the world, being used as little more than an extension of Stalin’s foreign policy.

Hitler-Stalin Pact

Unbeknownst to most rank-and-file communists at this moment, Stalin was seeking an accommodation with Hitler, which in a few months time would result in the Hitler-Stalin Pact of 1939. Stalin was gambling that by signing a non-aggression agreement with Nazi Germany, he could push Hitler into a new war with France and Britain, giving him time to rebuild the Red Army structure he had destroyed in the great purges of 1937.

Moscow, therefore, informed the KSC that despite the Nazi occupation of their country, their main enemy remained the Czech bourgeoisie backed by French and British Imperialism, while the KSC leader, Klement Gottwald, instructed KSC members that they should see the German Army as “… proletarians in soldiers’ uniforms and therefore in no way class enemies” (J. Pelikan, The struggle for socialism in Czechoslovakia, New Left Review, 1972).

The response of the Czech workers to this can be imagined. Not surprisingly, the next – and last until 1945 – mass display of resistance in western Czechoslovakia, by-passed these groups, with the students taking independent action.

Buoyed by Britain and France’s declaration of war on Nazi Germany in September 1939, the students called for mass protests on 28 October, Czechoslovakia’s ‘National Independence Day’. Around 100,000 joined the demonstration, but it was brutally suppressed by the Nazis, with German troops opening fire, killing two students and wounding hundreds of others.

The students would not back down however. The funeral of one of the murdered students ignited new student protests in Prague, Ostrava, Pilsen, Hradec, Kralore and Pribaum. This time the students felt the full wrath of the Nazi regime. The Gestapo and SS raided student halls and carried out indiscriminate vicious beatings. All universities were closed down. Nine student leaders were executed, and 1,200 student activists sent to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

Partition – Fascist Tiso rules Slovakia

The Nazis cut Czechoslovakia in two. The western Czech part became merely the ‘German Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia’. Hitler appointed SS General Reinhardt Heydrich head of the Protectorate, to ensure there were no more mass protests by either workers or students. Heydrich, as fanatical a Nazi as Hitler or Himmler and fellow architect of the ‘Final Solution’, unleashed such a wave of terror and oppression to atomise all resistance, the period is still known in the Czech lands today as ‘The Heydrichiada’.

It was a different story in the east however. The Nazis created a separate state of Slovakia, under the rule of their puppet, Father Joseph Tiso – a fascist, antisemite and anti-Protestant sectarian in equal measure.

His party, the Hlinka Slovak People’s Party had been formed by panicked landowners, factory bosses and the Catholic Church hierarchy in reaction to the short-lived Slovakian Soviet Republic of 1919. It merged with the fascist ‘Home Defence’ party, and their main enforcers were the Hlinka Guard paramilitary organisation. They ruled with an iron fist in the name of the Nazis.

The Tiso regime banned the trade unions and all opposition parties, not just the Communists, but also the mass Social Democratic Workers Party, the German SDP (supported by the Ethnic-Germans, many of them miners) and the United Socialist Zionist Party, backed by Jewish workers.

The regime arrested communists and workers’ leaders, began rounding up Slovakia’s Jewish population for ‘deportation’ to Poland, and implemented the sectarian harassment of Protestants, who had support mainly in industrial areas.

Tiso’s authority received a hammer blow within less than a year however. In March 1939, fascist Hungary invaded equally fascist Slovakia, and the Slovakian Army was defeated in a short, sharp three-day war. To add to Tiso’s humiliation, he was instructed by Nazi Germany to cede Slovakian territory to Hungary.

This early defeat resulted in sections of the Slovakian ruling class beginning to have doubts about Tiso and fears they had ‘backed the wrong horse’. It manifested itself as dissension among the senior officers of the Slovakian Army, still smarting at their embarrassing defeat.

But the main developments were at ground level, in the labour movement, the most politically explosive being amongst the Communists. Historically, the Moscow driven ‘party line’ for the KSC was delivered via the KSC leadership in Prague. Cut off from them, the Slovakian Communists began to think independently.

Firstly, they were not troubled by the confusion caused by Gottwald’s slogan that the exiled Benes government and its imperialist backers were the ‘real class enemy’, not the Nazi invaders. The Slovakian’s home-grown bourgeois was right there before their eyes in the form of the Tiso regime. Not even the most contorted, twisted Stalinist ‘theory’ could contest that.

But secondly, the Slovakian Communists were stunned to learn that as part of the Hitler-Stalin Pact, Stalin had agreed that the Soviet Union would formally recognise the new fascist Slovakian state of Tiso. They were now members of a party where the head of the international Communist movement had recognised the very regime that was killing, imprisoning and repressing them. The KSC collapsed.

Communist Party in Slovakia (KSS) – new party splits from Stalin line

The Slovakian Communists formed a new organisation, calling themselves ‘The Communist Party in Slovakia’ (KSS). For good measure, their central slogan – in a snub to the collaborationist party line from Moscow – was “For a Soviet Slovakia!” Despite requests from the KSS to join the Communist International (the Comintern), Moscow, which had officially recognised the Tiso regime, refused to recognise the KSS!

There was a similar process underway amongst rank-and-file socialists in the Social Democratic parties, which were moving sharply to the left – they too were cut off from the right-wing leaderships in Prague: rather than ‘remaining faithful’ to the Benes government and a return to ‘business as usual’ after victory, they wanted liberation to bring socialist policies.

The KSS were better prepared for underground work, as for much of the 1930s, the ‘democratic’ Benes government had banned the Communist Party. The KSS reverted to their old cell structure with four or five members in each cell, making it difficult for the Tiso regime to penetrate the KSS.

Bourgeois nationalist President of Czechoslovakia before and after the war.

More importantly, free of the dead hand of Stalinism, the KSS reverted – perhaps subconsciously – to the policy of Lenin and Trotsky of 1921, of building a United Front of workers’ organisations against fascism. Rather than conspire against or denounce the socialist organisations, they built upon the instinctive desire of all workers to unite against the fascist enemy.

Both the KSS and the socialists soon had a fertile recruiting ground. Unlike Heydrich in the west, Tiso found it impossible to crush the labour movement. From 1940 onwards right up until the uprising itself, there were several major strikes in Slovakia’s key industries – the mines, the railways and the textile factories. They were suppressed, but as soon as one strike was crushed, another sprang up in a different sector. The strikes were over pay and conditions only, but all disputes raise class consciousness and soon willing recruits were found for the growing resistance movement.

There was a nationalist element too, particularly amongst the Army officers. The east had always been the junior partner in Czechoslovakia, with most wealth and authority concentrated in the west. Yes, they would fight for the liberation of all of Czechoslovakia, but this time they wanted Slovakia to be an equal partner in the liberated state.

Hitler invades Soviet Union. Slovakian resistance formed.

In 1941, the world shifted on its axis when Hitler invaded the Soviet Union. Despite an early initial near collapse, the Soviet Union rallied and after the victory at Stalingrad in 1943, the tide was turning in favour of the advancing Red Army.

It greatly enthused the Slovakian workers, and the KSS began setting up Partisan groups and carrying out acts of sabotage. Now they were courted by the dissident Army officers, whose numbers grew as the Red Army got nearer – many leading KSS members were in prison, and Army officers, supposedly their prison guards, held secret talks with them, a perfect cover from the prying eyes of the Tiso regime. The Army officers also began stockpiling weapons, ammunition and money at barracks under their control.

The KSS and the socialists agreed to form a Slovakian National Council with the Army officers, to co-ordinate resistance and plan for a national uprising, with the former ensuring that it was not just a question of ousting Tiso, but the new liberated country would include a socialist programme.

Most importantly, the SNC agreed to establish ‘Revolutionary National Committees’ (RNVs) at local level. This was not going to be a ‘top-down’ resistance movement, but was a participatory movement and one that actively organised and involved all the people. Soon, RNVs were clandestinely established in every town and village, laying the basis for a mass Partisan organisation: “The RNVs were crucial to the armed uprising, both as symbols of a united resistance and in terms of organising. The highest density of RNV networks was in central Slovakia, which would become the epicentre of the uprising” (Tomas Tengely-Evans, The Slovakian National Uprising of 1944, 2015).

The planned uprising was given further impetus in April 1944. Two Slovakian Jews, Rudolf Vrba and Alfred Wetzler, carried out an incredible act of bravery. They had been sent to the Auschwitz death camp, and managed to escape. But before they did, in the most dangerous of conditions, they put together a detailed report about the operation of the gas chambers.

Evidence of the Holocaust

It should be remembered that throughout most of World War II, the Allied side were sceptical of the reports from the few who had escaped, about the Nazi’s murderous construct of the assembly-line genocide of Europe’s Jews. But now Vrba and Wetzler had the hard evidence. It would take them some time to convince the Allies, but in Slovakia at least, the country’s remaining 20,000 strong Jewish community now knew they were not being deported for ‘resettlement’, but certain death. It had an electrifying effect, and not surprisingly when the uprising came, despite their small number, disproportionally Jewish fighters made up over 10 per cent of the Partisan forces.

The establishment of the Slovakian National Council shocked the Western allies, Benes and Moscow. They wanted all resistance movements to be under their strict control, for use at best as an extension of their military operations. Both feared a repeat of the end of World War I, when the shockwaves from the Russian Revolution saw socialist revolutions in Hungary, Austria, Slovakia, and Germany. It had been a close-run thing for European capitalism in 1919.

The Western allies did not want all their efforts to result in a workers socialist democracy in liberated areas: paradoxically, nor did Stalin, as a functioning workers’ democracy would raise questions at home about democratic rights and the role and privileges of the Stalinist bureaucracy, that sat atop the Soviet masses like a deadweight.

Indeed, control of liberation movements was an even more urgent concern for Stalin. He was desperate for support and intervention by the Western allies fearing, with some justification, that they would sit back and watch Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union fight each other to the death, and then move in over their remains for all the rich territorial pickings.

Comintern shut down

As such, to prove to the Allies that the Soviet Union was not a threat to them, Stalin abandoned the cause of world revolution. He closed down the Comintern in 1943, and assured the Allies his aim was to install Popular Front governments in areas liberated by the Red Army which would be ‘progressive capitalist democracies’, although wanted a sphere of influence in the eastern European ones to ensure a buffer zone to protect the Soviet Union from a repeat of the 1941 invasion.

zones of influence

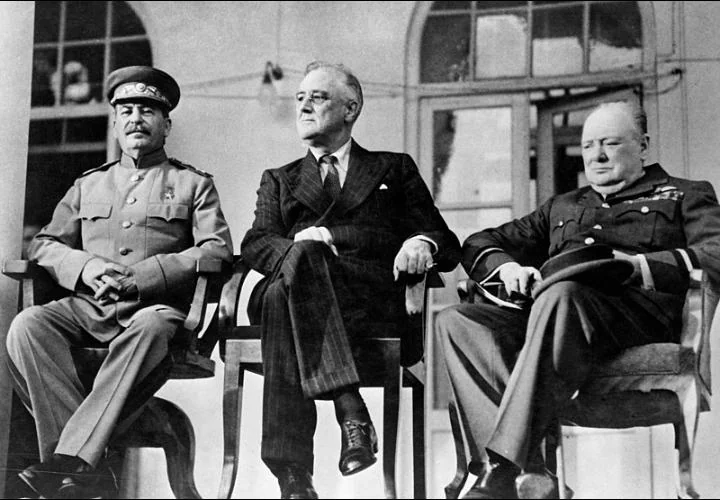

At the Tehran conference of the ‘Big Three’ – Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin – the Allies agreed, and carved up Europe into respective ‘spheres of influence’ between them. For Stalin, this included Czechoslovakia – Benes was amenable to Stalin, not trusting the Western Allies after the betrayal at Munich, and the two signed a ‘Co-operation Treaty’. They also both agreed that the Slovakian resistance and their dangerous ideas needed to be brought back into line.

Part of the deal was for Stalin to establish a Soviet Partisan force in Ukraine, which would then infiltrate into eastern and northern Slovakia. They were supposedly there to ‘help’ the Slovakians. However, as Tengely-Evans points out: “… Stalin had no intention of supporting a ‘Slovakian National Uprising’, just as he was letting the Warsaw uprising go down to defeat”.

The Warsaw uprising was coming to its close, and there had been widespread criticism of the Soviet Union for halting the advance of the Red Army – it was in the interests of Stalin that the uprising by Polish Nationalists be crushed, giving a freehand to Stalin’s Polish supporters when the city was liberated.

The Slovakian suspicions were soon borne out, in August 1944. Despite appeals to the Soviet Partisans, now in Slovakia, not to carry out provocations that would draw in a new round of repression and possible German invasion that could disrupt preparations for the uprising, the Soviet Partisans attacked a German column retreating from Romania.

1944 – German invasion of Slovakia

The Nazis, long contemptuous of the weak Tiso regime, had intelligence that the Slovakian Army was going to mutiny, and the Soviet Partisan attack was the ‘excuse’ they needed. On 29 August 1944, 48,000 German troops, half of them Waffen SS, and a Panzer Division poured over the Slovakian border, supposedly at the request of Father Tiso who – displaying his shopping list of hate – denounced the approaching uprising as a “Czecho-Lutheran-Jewish-Bolshevik putsch”.

This threw the SNC into confusion, with fears that their uprising could be premature.

The reliability of the Slovakian bourgeois represented by the dissident officer corps was soon exposed. One half of them went on the air to call on the Slovakian Army to lay down their weapons before the Nazi invaders.

Those officers that did chose to fight were of dubious assistance. The rebel officers in charge of the two best, heavily-armed, Slovakian Infantry Divisions went against the agreed plan to join the uprising, and instead flew to Poland (some would say fled) to appeal to the Red Army to invade. The two Slovakian Divisions were surrounded by the German Panzer division – now leaderless, they promptly surrendered without firing a shot. Around 3,500 Slovakian soldiers quickly deserted in disgust to join those who would fight: the Partisans.

Only the rebel Lt Col Jan Golian and his Army group remained firm, with Golian transmitting the agreed SNC codeword to begin the uprising: “Start the Evacuation”. The fight was on – although earlier than they had hoped.

Slovakian Partisans push back

Leading KSS member Karol Smidke was appointed by the SNC as commander of the Slovakian Partisans. Initially, a force of 18,000 Slovakian Partisans began to push the Germans back.

By full mobilisation day of September 9, the Slovakian Partisans ranks swelled to 60,000 plus support from remaining rebel Slovakian Army units, as well as the Slovakian police. The Slovakian Partisans included one 2,000-strong column of Jewish fighters, and another made up of 1,400 escaped French POWs. Amongst the KSS Partisans was a young Slovakian KSS Youth Organiser called Alexandre Dubcek, the future leader of Czechoslovakia.

The 18,000 Soviet Partisans however still operated under Soviet control and would not co-ordinate their actions with the SNC command, but at least they were still fighting the same enemy.

One immediate victory was that Tiso’s Hlinka Guards at the Sered, Novaky and Vyhne concentration camps fled at first word of the uprising, and thousands of Jews awaiting transportation to the death camps escaped en masse to join the resistance.

Because the resistance, co-ordinated by the RNVs, rose as one, very rapidly they liberated over 20,000 km2 of territory, an area (sorry to use the cliché) the size of Wales, and with it, its population of 1.7 million.

Of course, we should not have a romanticised view, as all wars are ugly. Some Jews fighting in non-Jewish columns had to hide their identity because of antisemitism, while there were several incidences of Partisans massacring innocent Ethnic-Germans. In one instance, 150 construction workers were murdered who were actually helping the resistance build defence works, although in this incident the perpetrators were put on trial by the local RNV and executed.

Workers’ control

But it was what followed the military action that shocked the Allies, both in London and Moscow. The RNVs and trade unions seized all sizeable industries and put them under workers’ control. The SNC established itself as the government, and the central city of Banska Bystrica became the capital of Liberated Slovakia. Education was nationalised and taken out of the hands of the Church. A free press was established, and Free Slovak Radio began broadcasting. In the towns and villages, with mass support, the RNVs in effect became workers councils, or Soviets in the true sense. They organised supplies and recruits for the Partisans, and provided administration, policing and organisation.

A stunning example of what can be achieved by a socialised industry under workers control, was provided by the railway workers and engineers. Neither the Slovakian Partisans nor the rebel Army units had armoured vehicles that could match the German Panzers. Workers at the Slovak Railways workshops in Zvolen had the answer. In this mountainous country, the Panzers were restricted to the valley floors, just like the railways. Therefore armoured trains would help keep the Panzers at bay.

The agreement to build the trains – named after founders of Czechoslovakia – was just four days after the German invasion, on September 4. The first train, the Stefanik, was constructed in a record 14 days. The second, the Hurban, followed closely behind 11 days later. The third, the Masaryk, a week or so after that. These three colossal engines were designed and constructed in just five weeks, and now the Partisans had armoured artillery to match the Panzers virtually anywhere in the salient.

Equally important to the military campaign, was a political understanding of the twin pressures they would be under from the Western allies and Stalin, who – if the liberation was successful – would probably promote the dissident Army officers at the head of a new capitalist or Popular Front government, and all the social-economic gains the workers had won would be snatched away.

Socialist “United Front”

To defend their gains and for the labour movement to speak as one, the KSS and the Social Democratic organisations held a ‘Unity Conference’ amidst the fighting, on 17 September. It was attended by 700 delegates representing 46 RNVs, many of the key workplaces and 12 Partisan groups. It was agreed to merge their organisations into one at local level on the RNVs, to present a mass socialist United Front to not only the fascist enemy but also those ‘allies’ supposedly there to support the liberation struggle, in the haggling and manoeuvring they suspected would follow with Stalin’s plan for a Popular Front government.

Now the various Allied factions – supporters of Benes, the Stalinists, the Slovakian Army officers, the Western Allies – would have to deal with one united socialist bloc.

This was followed up by an equally significant trade union conference five weeks later. This was attended by 200 trade union delegates representing 130 key industrial plants. This also took the decision to merge the KSS ‘Red’ trade unions and the SDP trade unions, into one mass trade union. It then went on to formalise the practice of work place union committees running industry, which would now be by one united union.

Allies and Stalin intervene

All this confirmed the Allies’ worst fears. They had to intervene if they were to regain control of the liberation movement. Benes appealed to Stalin to release two Czechoslovakian Parachute Brigades fighting with the Red Army, for them to be sent into liberated Slovakia to take control. Stalin agreed. Not be outdone, the British government parachuted in a Special Operations Executive team to intervene, while the US government sent in three teams from the Office of Strategic Services, the forerunner of the CIA. They were attempting to impose control – as Tengely-Evans puts it, it became ”… an imperialist war from above, and a people’s war from below”

But the Slovakian Partisans were too mass a force to subjugate, despite the best efforts of Stalin. Red Army supplies flown in supposedly to support the uprising were diverted to the Soviet Partisans only, while – as in the Warsaw Uprising – offers of Western support to fly in supplies were blocked by Stalin.

The original plan had been to capture the Dukla Pass which connects Poland to Slovakia, through which the Red Army could advance. But, after two months of liberation, ‘defeat’ came because of events – the Red Army was switched from advancing on Slovakia to instead invade Romania, where the fascist regime had collapsed and the country had switched sides.

There have been suspicions that the diversion of the Red Army was a repeat of Stalin’s tactics over the Warsaw Uprising. But it has to be admitted that there were good military reasons for the Red Army suddenly prioritising advancing on Romania, as the Soviets needed to seize the Ploesti oil fields before the Nazis, to cut off the last major oil supply for Germany.

Vicious reprisals

However, this allowed Germany to release another 30,000 troops from Hungary to invade Slovakia from the south. This overwhelmed the Partisan forces, and the Nazis captured Banska Bystrica on 28 October, pushing the partisans back into the mountains. The reprisals were vicious, with over 100 villages being raised to the ground and thousands of civilians – mainly Jews and Roma – being massacred.

The few histories about the uprising say this marked the ‘end’. But actually 20,000 Slovakian Partisans may have been pushed back to the more mountainous regions, but they weren’t hiding or in retreat. They continued to carry out nearly 200 attacks on what were soon to be retreating Nazi forces.

Also, 15,000 Slovakian Jews survived the Holocaust because of the Uprising – 5,000 followed the Partisans into the mountains, and a further 10,000 who had been rounded up for deportation to the death camps in the final terror of 28 October, survived because of liberation by advancing Allied forces. Had the Uprising not delayed their deportation for two months, it would most likely have been too late to save them.

In addition, the industries taken over by the united trade unions remained nationalised, unlike the much of the economy in western Czechoslovakia when it was liberated, which was restored to private ownership (albeit briefly).

When the Red Army finally swept through Czechoslovakia, Stalin sent in the leading KSC member in exile in Moscow, Jan Sverma, to cajole the KSS back into the KSC, now the country was re-united. There was much bitterness from the Stalinist KSC towards the KSS:

“The Czech Communists went so far as to accuse many of the Slovakian Communists involved in the Uprising of being ‘bourgeois elements’ and ‘deviationists’, more interested in nationalism than socialism” (Slovakia 1944: the forgotten uprising, Sean Judge, 2008).

Dubcek – KSS veteran.

But with the country under the total control of the Red Army, the KSS complied, although the rift rumbled on for the next 20 years. Despite Moscow’s hostility, the KSS fighters retained popular support, and Dubcek rose through the ranks to become General Secretary of the KSC, and effective leader of Czechoslovakia. Demonstrating the old rebellious KSS tradition, with mass support Dubcek attempted to bring in social reforms during the ‘Prague Spring’ of 1968 – Moscow had its final revenge however as the Soviets invaded to crush the movement, and Dubcek was arrested, put on trial and exiled, with all the old Stalinist slanders against the KSS being dragged up.

After VE day in 1945, the Allies stuck by the agreed spheres of influence. The West initially ruled in the areas it occupied through open military repression, as in South East Asia and Greece. In the areas agreed as the Allied sphere of influence, the Communist leaders of the resistance movements were now instructed by Moscow to hand back power to the capitalists, most notably in France and Italy. In Greece, Stalin stood aside as the British Army crushed the Greek CP led resistance movement and restored the Monarchy.

In the areas in the Soviet sphere, ‘Popular Front’ alliances of capitalists and Communists were initially put in power, including with Monarchists in Romania, and former fascist supporters of the Horthy dictatorship in Hungary. In Czechoslovakia, Benes returned to be President, with KSC leader Klement Gottwald installed as Prime Minister.

It was a brief courtship however. In 1948, Benes approached the receptive Western Allies for a slice of Marshall Aid funding. This infuriated Stalin who saw it as a betrayal of the previously agreed ‘spheres of influence’, and the first stage of Czechoslovakia allying with the West. The remnants of the Czech bourgeois were liquidated in the ‘Prague Coup’ of that year, and, along with the other eastern European countries under Red Army control, Stalinist regimes were installed, but the ‘socialism’ imposed by Moscow was, as Ted Grant once put it, “… a state in the image of that where Stalin had finished and not where Lenin had begun “ (Programme of the International, May 1970).

History distorted

Under Soviet rule, the story of the Slovakian National Uprising was distorted by Moscow to give the impression they led it (rather than hindered it). After the collapse of the Soviet Union, in the new capitalist state of Slovakia the Uprising is still celebrated but all reference to the role of the rank-and-file communists and the socialist gains made have been expunged, with instead the ‘safe’ Lt Col Jan Golian feted as the hero.

As Dubcek would later complain: “… of the many officially sanctioned books and studies published in the past about the Uprising, only a few were more than propaganda” (Alexandre Dubcek, Hope Dies Last, 1993).

Now, with the recent election victory of the Smer-SD party in Slovakia, which may rest upon a coalition of far-right parties who see themselves as the legacy of Father Tiso and who have previously disrupted anniversary celebrations of the Uprising, the heroic event may be driven out of history completely.

The Slovakian National Uprising was a heroic episode, but despite the huge area liberated of nearly two million people and holding out for two months, it barely receives a passing mention in all the volumes dedicated to the history of World War II. This is because it does not fit the narrative of either Western capitalism or former Soviet Stalinism. This narrative has no place for the Slovakian Partisans who had started to build a society ‘where Lenin had begun’.

What a great article. I had very little knowledge of this episode of the war.

Thanks Andy – I didn’t know about it either, which is why its such a long article because it was all news to me too!

I found out about it when I was down at my union conference earlier this year which was held at the TUC – I went to see if the old ‘Book Marx’ bookshop was still there and it was. And I found this book that you’d probably find interesting too:

‘ Fighting on All Fronts – Popular Resistance in the Second World War’, edited by Donny Gluckstein, Bookmarks, 2015. Its ‘SWPish’ but well researched.