By David Cartwright, Glasgow Anniesland Labour Party member and Gray Allan, Falkirk Labour Party member

30 November 2023 marks the 100th anniversary of the death of John MacLean in his home town of Glasgow at the age of just 44. MacLean was undoubtedly one of the most significant socialist leaders in the world in the tumultuous period of the early 1900s.

Some historic figures in the socialist movement are remembered for their educational work, others for their oratory, others for their political analysis of world events, and others for leading vital struggles of the working class. John MacLean will be remembered for all of these things. Reading any account of his life, you get a sense of a man with an incredible amount of energy and commitment to the cause of socialism. Even in his final year, he contested council by-elections in May, June and July, using each opportunity to distribute socialist material to the electorate.

What is extraordinary about his high level of political activity, is that between 1916 and 1922 he was jailed several times, spending a total of 38 months inside, which had a very harmful effect on his health. In 1921 he went on hunger strike in protest against being detained prior to trial. He was forcibly fed and complained about having his food drugged. In his election address for the 1922 general election he wrote: “Although getting food through ‘friends’ I found that my food was still being drugged and I gave out a bottle of cocoa and one of tea to William Stewart, Scottish Organiser of the ILP (Independent Labour Party), showing clear evidence that these drinks had been interfered with.”

MacLean and Marxism

All of MacLean’s political activity was imbued with an understanding of the contradictions of capitalism, gained from the ideas of Marxism, and how they related to his own experiences. He was born into a poor household on 24 August 1879 in Pollokshaws, Glasgow. His mother had come to Glasgow from Fort William as part of the Highland clearances and spoke no English when she arrived. His father was similarly evicted from the Isle of Mull. He worked as a potter in Bo’ness and died of an industrial disease when John was just 8 years old.

Growing up in Pollokshaws, MacLean was surrounded by pubs and churches, which he rejected in favour of working class education. He did teacher training in 1988-1900 walking a ten mile return trip every day. His early political activity was in the Pollokshaws Progressive Union, which he joined in 1900. This Union campaigned for social reforms and also had regular discussions on science, literature, philosophy and politics. This is where MacLean started to develop his understanding of the capitalist system of his day. It was then a natural step for him in 1903 to join the Social Democratic Federation (SDF), a Marxist party that had been created by Henry Hyndman in 1881.

The following extract from his election address of 1922 shows the strength of his commitment to revolutionary Marxism: “I object to the existing form of society, now known to everyone as capitalist society. Why? Because so few people own the world (outside Russia) and the factories of machinery and wealth production. These are the propertied class, including landlords, capitalists and moneylenders. Most other people have to sell their brain-power or body-power, in short their labour-power, to this class for a return in money called wages. This class is the wage-earning class, or the wage-slave class.”

MacLean became an effective Marxist agitator and did speaking tours around Scotland in the summer holidays when he was not teaching. The SDF became the Social Democratic Party (SDP) in 1908 and then merged with some disillusioned Labour Party members in 1911 to form the British Socialist Party (BSP). He was active in the big workers struggles of the time (1911 to 1914 has become known as ‘The Great Unrest’). As well as several miners’ strikes there was a massive strike in 1911 at the Singer sewing machine factory in Clydebank, where 11,000 workers all stopped work in solidarity with 12 female workers who had been threatened with longer hours and lower pay.

Independent thinker

What stands out with John MacLean’s approach to political questions, is his independence of thought. Although he saw the need for organising together with other socialists and Marxists, he was always prepared to challenge views that he thought were wrong. A case in point was his relationship with Hyndman, who took a nationalistic approach to the prospect of a war with Germany. In July 1910, Hyndman wrote an article in the Morning Post, advocated a ‘big navy’, claiming that the navy was a defender of the right of asylum and a champion of national liberty. In contrast, MacLean maintained a principled stand against the prospect of an imperialist war, placing him in solidarity with Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxembourg, who maintained the same stand in Germany. His opposition to the war led to his first stint in jail in November 2015.

His independence was shown again later during the attempts to create a unified Communist party in the wake of the successful workers’ revolution of Russia 1917. Lenin and the Bolsheviks had shown how highly they regarded him, by appointing him Bolshevik consul for Scotland in February 1918 and making him an honorary president of the first All Russian Congress of Soviets. Yet, when the Third International (Comintern) encouraged the BSP and other parties to come together and form a unified Communist party, MacLean opposed it, considering the influence of the Comintern too great on its intended workings. However, he felt that this was a time of revolutionary opportunity and helped establish a Labour college bringing together the colleges of the SLP and BSP.

The Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) was finally created at a unity conference in the summer of 1920. John MacLean could not take part because had been expelled from the BSP in Easter that year for his continued opposition to a single British wide Communist Party. Another factor in his expulsion was his total opposition to the BSP decision to welcome onto its Executive Committee, Lieutenant Colonel Malone, once a Liberal MP and former member of the Reconstruction Society (the name for the Anti-Socialist Union at that time), vehement opponents of socialism and the Russian Revolution.

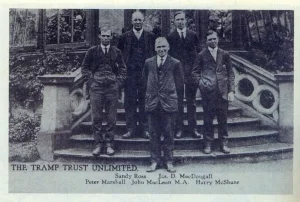

Very few branches from Scotland attended the conference, partly because they disagreed with its avowed aim of affiliating to the Labour Party, and MacLean attempted instead to set up a Scottish Communist Party. The Comintern still insisted that there should be just one Communist Party in Great Britain and wanted the new party to reach out to people like MacLean. Willy Gallagher played a pernicious role at this time. Whilst claiming to bring back from Russia the message of a single party, he actually set about creating a separate party in Scotland called the Communist Labour Party. He also set up a new propaganda team called the Tramp Trust Unlimited, which included Harry McShane, member of the Clyde Workers’ Committee and fellow anti-war campaigner, who later split with MacLean and joined the CPGB.

Disagreements within the developing ‘communist’ movement

MacLean became increasingly irritated with the way the CPGB was operating. He considered Gallagher to be an anarchist and declared in the Vanguard newspaper, formerly the organ of the Glasgow district BSP, “If Lenin tells us to unite with the elements who are anarchists, we must reply by asking the Bolsheviks to unite with the Mensheviks or the Social Revolutionaries… The less Russians interfere in the internal affairs of other countries at this juncture the better for the cause of revolution in these countries.”

Looking at this comment, it appears as though MacLean and Lenin did not get the opportunity to discuss and debate ideas together. Lenin wrote a pamphlet in May 1920 called “’Left-Wing’ Communism, an Infantile Disorder” which includes a chapter on Great Britain. In that section, Lenin challenges the approach of Gallagher as well as others in the Communist party at that time like Sylvia Pankhurst. Lenin recognises Gallagher’s strength in being able to express the ‘temper of the masses’ but warns against mistakes like refusing to participate in parliamentary action. Lenin had understood developments in Britain. Rather than interfering he was giving the advice that you would expect of your comrades internationally.

What Lenin had understood was that, whilst all these attempts were going on to unify the various strands of ‘Marxism’ into a Communist party, the Labour Party was steadily becoming a mass party of the working class and a correct approach to it was required. The Labour Party received just over 370,000 votes in the 1910 General Election, then 2.4 million in 1918 and it was to go on and win 4.3 million in 1923, denying the Tory party an overall majority.

The various Marxist groupings of the day often assessed and re-assessed their approach to the Labour Party as it grew in support amongst workers. In fact, the BSP joined the Labour Party in 2016 and John MaClean stood as the Labour Party candidate in the Gorbals in the 2018 General Election. He had just been released from prison following the armistice. He stood against George Barnes, the former Labour Party leader, who had refused to leave the Lloyd George coalition and, hence, had been expelled from the Labour Party earlier that year. Despite his best endeavours MacLean was unable to unseat Barnes.

Internationalism and the call for a “Scottish Workers’ Republic”

Nevertheless, MacLean always had an internationalist approach, particularly on the questions of empires, colonialism and war. He brought these world events to the attention of workers in his writings and speeches. He was particularly interested in the struggle in Ireland and visited Dublin in 1920 on the invitation of Delia Larkin, sister of James Larkin, the Trade Union leader and socialist colleague of James Connolly.

The effect of the oppression in Ireland, was a big factor in his calling for a “Scottish Workers’ Republic”. In the Vanguard in 1920 he wrote “I hold that the British empire is the biggest menace to the human race … The best interests of humanity can therefore be served by the break-up of the British empire. The Irish, the Indians and others are playing the part. Why ought not the Scottish?” The British empire has long since collapsed, but capitalism still ruled in England, Scotland and all the former colonies.

I wonder what MacLean would think of the ‘lefts’ who still call for a “Scottish Workers’ Republic” in these very different times. Some of them argue that even on a capitalist basis, Scottish independence would deal a blow to the British/English state. In fact, the nationalism generated on both sides of the border would strengthen the capitalist state rather than weaken it, by directed workers’ consciousness into the channel of nationalism rather than class politics.

Another reason that MacLean gave for his position, was that he believed that the Scottish workers were more advanced politically than those in England. He thought, for example, that the campaign to reduce the working week to 40 hours was taken up more urgently by the workers in Scotland. If he had lived beyond 1923 and experienced the various united movements of the British working class, like the 1926 General Strike, he might well have reconsidered his assessment. In any case, then as now, a socialist Scotland would not be possible without the socialist transformation of England and Wales as well, which requires the united struggle of workers across Britain.

MacLean’s legacy

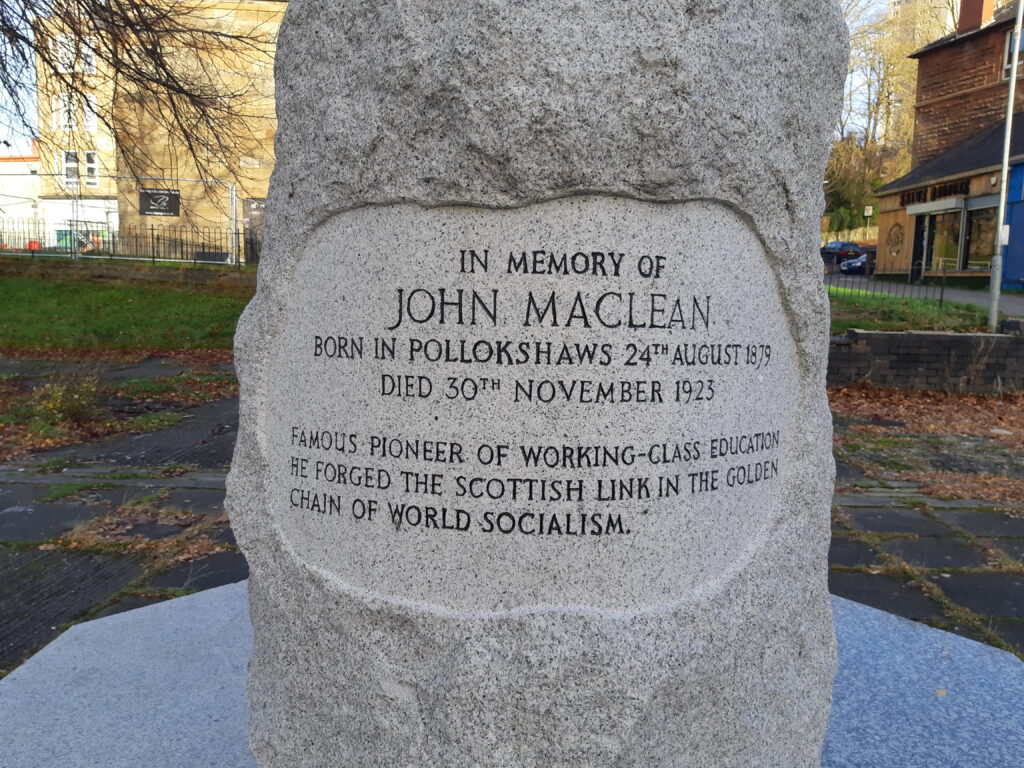

Memorial cairn erected in 1973 in Shawlands, Glasgow

15,000 people attended the funeral of John MacLean. During his lifetime he reached hundreds of thousands of workers with the ideas of socialism. He was a tireless fighter for the cause of the exploited classes. In 1923, he continued his attempt to build revolutionary forces separate from the Communist Party of Great Britain and the Labour Party. He formed the Scottish Workers’ Republican Party (SWRP) and continued his traditional approach of education and campaigning. The newly formed branch in the Gorbals recruited 100 members. 3,000 people turned up each Sunday to listen to his speeches at Glasgow Green and weekly classes in places like Partick and the East End attracted 40-100 attendees.

His death in 1923 was a big loss for the international socialist movement.

On the fiftieth anniversary of his death in 1973 a memorial committee was established which led to the erection of a memorial cairn in Shawlands, Glasgow. The cairn sits in a working class area with small local shops to one side and tower blocks just around the corner. A fitting reminder of a man who fought to represent the working class community that he was part of.