By Richard Price, Leyton and Wanstead CLP member.

Periods in which foreign policy has dominated over domestic politics in Britain over the last 70 years have been few and far between – 1956, with the impact of the Suez Crisis and the Hungarian Revolution; the Falklands War in 1982; Iraq in 2003; and the current Gaza crisis. You could also add Brexit at various points between 2016 and 2019, although ‘getting Brexit done’ was arguably as much about domestic as it was about foreign policy. Each one of these rare events led to a major shift in the political situation.

Since October 7, I’ve met people who think that the anti-war movement has the potential to topple Starmer, and others who say that protests never prevent wars, and therefore Gaza won’t have much of an effect on the next general election. People will vote on the economy, they argue, because they are desperate to have a change of government.

With the air thick with comparisons to Iraq, it’s sometimes hard to remember just how popular Tony Blair was before 2001. Asked what he thought of Blair’s approval rating, which had soared to 93% following ‘People’s Princess’ Diana’s funeral in September 1997, Bob Marshall-Andrews MP uttered the immortal words: “Seven per cent! We can build on that!”

By 2003, despite growing criticism of privatisation and PFI, and with wage growth stalling, Blair’s domestic agenda was still reasonably popular. It was Iraq that did New Labour long term reputational damage. Trust in politicians – further weakened by the 2009 expenses scandal – never returned to pre-2001 levels.

Labour’s vote fell successively from 13.5m in 1997, to 10.7m in 2001, to 9.5m in 2005 to 8.6m in 2010. Although there were other factors at work, New Labour’s loss of nearly 5m voters showed that foreign policy, particularly in relation to the Middle East, could be a powerful factor in voting behaviour. It condemned Britain to a decade of austerity, and it would, of course, take Jeremy Corbyn to restore Labour’s support to 12.8m in 2017, in a campaign in which anti-austerity and the reassertion of an ethical foreign policy played prominent roles.

Comparisons with Iraq

The invasion of Iraq in March 2003 was preceded by a lengthy period of political and military preparation during the winter of 2002-3, during which the claim that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction was debated and disputed globally. Anti-war sentiment grew steadily, culminating in the largest demonstration in British history on February 15, 2003. Opposition to the war made deep inroads into the Parliamentary Labour Party, leading to the resignation of Robin Cook and a record rebellion of 139 Labour MPs on March 18.

This time around, Labour is in opposition and British forces are not directly committed to the conflict. Instead of a long, slow build up, the events of October 7 and their immediate aftermath came as a shock to the world, in spite of Egyptian claims that it had forewarned Israel.

In spite of this, the movement to demand a ceasefire has spread like a forest fire, with the national demonstrations on October, 21, October 28 and November 11 all among the ten largest demonstrations on record.

The character of the anti-war movement

To a greater extent than 2003, Muslim communities have been the driving force of the protests. Mosques across Britain have systematically lobbied Labour MPs and councillors. Young Muslim women, whether students or mothers with pushchairs, have been a notable and vibrant presence on the huge marches in London, and Muslims have accounted for around two-thirds of demonstrators.

The flipside of this has been the smaller proportion of non-Muslim protestors. On October 14 – in an email to CLP and branch secretaries sent after 11am, when many were already on their way to demonstrations – Labour General Secretary, David Evans, attempted to lay down the law. MPs and councillors were barred from attending demonstrations, and members urged “to exercise similar caution”. Evans also sought to ban Labour Party banners being carried.

Factor in that many Labour branches had met a few days before the Hamas attacks on October 7, and wouldn’t meet again until early November. Also, the obstructions placed on CLPs debating Gaza in many areas, including an apparent total ban in Scotland, despite Anas Sarwar’s public support for a ceasefire and Labour MSPs voting for one, and it is possible to see why Labour opposition has taken several weeks to build. The role of the trade unions, in contrast to the prominent role played by several general secretaries on Stop the War platforms in 2003, has been modest.

But build it has, with a steady drip-drip of councillor resignations that have resulted in power in Burnley now resting with a power-sharing agreement between the newly formed Burnley Independent Group, the Green Party and Liberal Democrats; high profile multiple defections in Blackburn, Oxford and Walsall and smaller ones in Pendle, Nottinghamshire, and several London boroughs.

The ban on MPs taking part in demonstrations was effectively dead in the water by October 21. Members of over 500 CLPs have called for a ceasefire, along with ten Labour frontbenchers, while a number of other frontbenchers are said to be on ‘resignation watch’. An early day motion calling for “an immediate de-escalation and cessation of hostilities, to ensure the immediate, unconditional release of the Israeli hostages, to end the total siege of Gaza” has 101 signatories to date, including 42 Labour MPs, plus Jeremy Corbyn, Diane Abbott, Claudia Webbe and Andy McDonald; 56 Labour MPs voted for a ceasefire in the Commons on November 15.

Clearly, the rebellion has not yet reached 2003 proportions. Yet, the impact of Gaza on Britain’s Muslim communities has, if anything, been more profound than it was then. Iraq and its bloody aftermath produced spectacular victories for George Galloway in Bethnal Green and Bow and in Bradford West, but elsewhere Respect’s successes were more modest.

This isn’t explained by the respective body counts. Estimates of civilian deaths in Iraq are as high as 600,000, whereas the carnage in Gaza has so far accounted for around 14,500 Palestinian deaths. What has changed is the reach of social media. In addition, Al Jazeera has several million UK viewers. This has brought a graphic immediacy to news consumption and a transformation in how people communicate with each other. The appalling proportion of children among the dead – over 40% of the total – has had a visceral impact, particularly among women.

The weight of the ‘Muslim vote’

While all this was going on, Labour HQ was reportedly gaming the effect of Muslim defections and abstentions at the next general election – an appropriately cynical response to a political crisis. This is no easy calculation. No doubt HQ is taking some comfort from the fact that constituencies with large Muslim electorates tend to have big Labour majorities. It’s also likely that Muslims will break in different directions. In a handful of seats, independents, particularly those will strong local support or a national profile, could be in with a shout. In other seats, abstentions are likely to rise substantially.

Some Muslim voters may be attracted by the Lib Dems, whose MPs voted for the SNP’s ceasefire amendment. That said, the Lib Dems have been muffling the drums over Gaza, no doubt so as not to frighten the horses in the Tory seats that are their most realistic targets at the next general election. Tory voters are mostly happy with Sunak’s performance during the Gaza crisis. In Scotland, the anti-war SNP, led by a Muslim First Minister, is an obvious pole of attraction.

The relative proportions of these different groups are unknowable at this stage, and this is reflected in the wildly varying survey data, such as it is. One survey gives Muslim voters a decisive role in ten constituencies; another says thirty constituencies. Those using the definition of Tory seats with majorities smaller than the local Muslim electorate are guilty of some fairly elementary double counting. We should also note that changes to voter registration have impacted black and Asian communities disproportionately.

In my experience of working on government social surveys, those concerning ethnic minorities presented particular challenges when creating representative samples. The data underlying the fairly-widely held perception that Muslim voters turn out in larger numbers than the general population is fairly shaky. As imam Musharraf Hussain regretted in 2019, “In previous elections, the Muslim turnout has been relatively low.”

A widely reported ‘snap’ survey jointly commissioned by Muslim Census and Muslim Engagement and Development and published on October 17, shows a fall in Muslim support for Labour from 71% in 2019 to 5% currently. But an online poll for Savanta, conducted in late October and early November, found that 84% of those who voted Labour in 2019 said they would do so again, and that Gaza was only fourth in their priorities. These are surely either outliers at opposite ends of the spectrum, or the result of some questionable methodology. It certainly doesn’t feel like that on the ground.

But if the truth lies somewhere between these two doubtful results, we should remember that we are asking people to predict their voting behaviour at a general election that may be a year away. We neither know when the election will be, nor how long the war in Gaza will last.

Vietnam taught us that tunnel fighting presents attacking armies with serious difficulties. With Israeli military strategists talking of ‘months’ of war in the rubble of Gaza, who knows what the casualties will be by then? Will major epidemics have broken out? Will Gazans be dying of starvation? One thing seems clear: the longer the war goes on, the worse it will be for Starmer, who remains in lockstep with Joe Biden and without an exit strategy when things turn even worse.

While the Savanta survey paints a rosy picture for Labour number crunchers, it is undeniable that for large numbers of voters the next election will be about the ongoing cost of living crisis, energy and food inflation, the NHS and the housing crisis. Domestic issues dominate voters’ priorities.

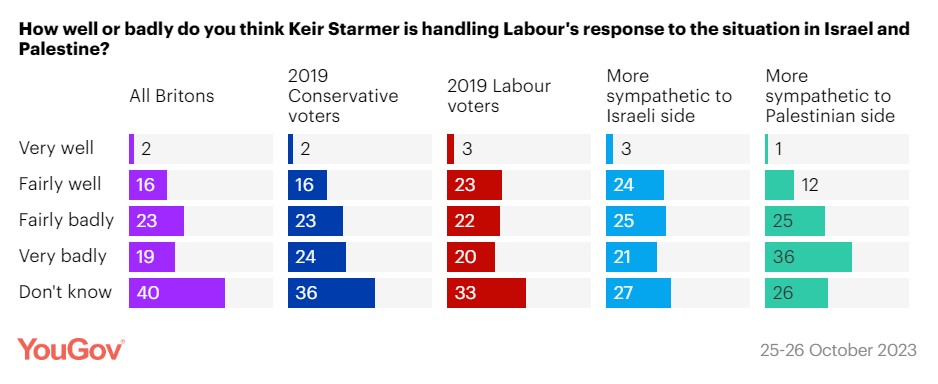

Despite this, how politicians react to a humanitarian crisis of this scale is a test both of political morality (or its absence) and of trust, and can powerfully influence the political climate. Polling tells us that the public have been deeply unimpressed with Starmer’s leadership in the Gaza crisis – a YouGov survey, published on October 27, found that 42% of 2019 Labour voters think that Keir Starmer has badly handled Labour’s response to the situation in Israel and Palestine, including 20% who say he has handled it “very badly”. By contrast, only 26% think he has handled it well.

Perceptions formed during wars tend to stay with us. Voters may have preferred Labour to the other options in 2005, but for millions (including not a few Labour Party members) Tony Blair would remain ‘Bliar’ – a man not to be trusted in any conceivable circumstances.

Starmer’s authority has also taken a serious hit. According to most of the media, Starmer had the world at his feet by the time the Red Flag was sung at Labour’s Conference on October 11 – the left smashed, the City reassured, a big poll lead, a landslide in Rutherglen and Hamilton West under his belt, and parliamentary selections fully under control.

Yet his disastrous interview on LBC the same morning set in motion a Thick Of It-style omnishambles in which – after a nine-day pause – Starmer’s people offered a variety of mutually exclusive ‘clarifications’ of what he had meant. He had mis-spoken. He had spoken correctly, but had been answering a different question. Or the video had been cunningly edited. Take your pick.

To lose Imran Hussain from the front bench was unfortunate. To lose ten frontbenchers, despite all the arm-twisting behind the scenes, and the dispensations given to MPs with large Muslim electorates, to a 56-strong rebellion in support of the SNP’s ceasefire amendment, looked like carelessness.

Uneven development – the ceasefire movement across Britain

Part of the problem of sketching out the likely development of the anti-war movement is its unevenness across Britain. Support for the movement maps closely to concentrations of Muslims. The strongest reactions have tended to come from the North-West and the Midlands – the former industrial towns of the West Riding and Lancashire, Manchester, Liverpool, Birmingham, Leicester and Nottingham.

London has provided hundreds of thousands of marchers on national demonstrations. Scotland has managed to have significant demonstrations in four cities. In less multi-cultural cities, towns and rural areas the impact has been much less. Gaza did not appear to have any discernible effect on the Mid Beds and Tamworth by elections, held on October 19, twelve days after the Hamas attacks. It is important that we don’t generalise from our experiences in our local areas.

Another notable feature has been the rash of occupations and protests, some of them largely spontaneous, some organised by community groups. Many students are fully engaged, and a number of professional groups have issued pro-ceasefire statements. On the weekend of November 18-19, a hundred local and regional events took place across Britain. There are no signs of protest fatigue.

What size crisis is this for Starmer?

The saving grace for Starmer is Labour’s commanding lead in the polls, in the face of an imploding Tory government. Despite some suggestions that it has narrowed in recent weeks, Politico’s poll of polls still has Labour 20 points ahead. This suggests that Labour could take a hit of several per cent and still win a landslide. A handful of polls suggest the gap is closer at around 12%. If I were Starmer, and the lead reduced to single figures, I’d be getting worried. Starmer’s approval rating (at least according to YouGov) has not suffered dramatically – down from minus 12 on October 9 to minus 14 on November 6.

The nightmare scenario for Starmer would be the double-whammy of the Labour lead over the Tories narrowing and a determined campaign to run credible independent candidates against Labour. Labour could be vulnerable in several seats in London, in parts of Birmingham, in Bradford, as well as a number of Red Wall seats in the north-west. It could trim Labour’s ambitions in Scotland.

Next year’s general election will offer a uniquely unappetising menu – the Tories, deeply unpopular, steadily imploding for the last two years; Labour, benefiting from Tory unpopularity, but with large numbers of voters unclear what it stands for, and a leader the public hasn’t taken to; the SNP, riven by internal struggles and unwelcome police attention; the Lib Dems, keeping a low profile, with their sights set on picking up a modest number of Tory seats; the Greens, pretty much where they ever were, with little sign of a Green bounce, despite the climate crisis.

The disenchantment of voters with politicians in general could well depress turnout. (It was only 61.4% in 2005.) If – and it’s a big if – independents manage to rally serious campaigns, while disenchanted Labour and Tory voters stay at home, we could see some interesting results.

The big damage to Blair happened when he was in office, sitting on top of a decent majority. Assuming Labour does win a majority next year, Starmer will be entering office as damaged goods. Short of a highly improbable cessation of hostilities, without many more casualties, nothing is likely to get better for Starmer in relation to Gaza. He will remain bound hand and foot to Biden, bleating for restraint while Gaza is ground into dust.

So what size crisis is it? For Starmer, it’s certainly medium sized; not impossible to survive by any means for all the reasons I have suggested, but damaging nonetheless, and with the potential to get worse. For the Party internally, it’s worse. The leadership’s stance on Gaza has created chaos. The right doesn’t really have activists these days, outside of the payroll – councillors, Labour Group officers, borough organisers, HQ and regional staffers – and a smattering of recently ex-students, hoping to join this illustrious band.

The centre and the left, who do most of the canvassing and leafleting, don’t want to turn out for very much right now, except demonstrations. All this in the run-up to a general election. Thank goodness the ‘grown-ups’ are back in charge.

Note: since this article was first published, Labour lost a council by-election in Plaistow North (London Borough of Newham) to an Independent. This is a council where Labour won every seat in the 2010, 2014 and 2018 council elections. The result comes after another Newham councillor joined 61 other councillors in resigning from the Labour Party this week over the Party’s stance on Gaza.

First published in Labour Hub, here.