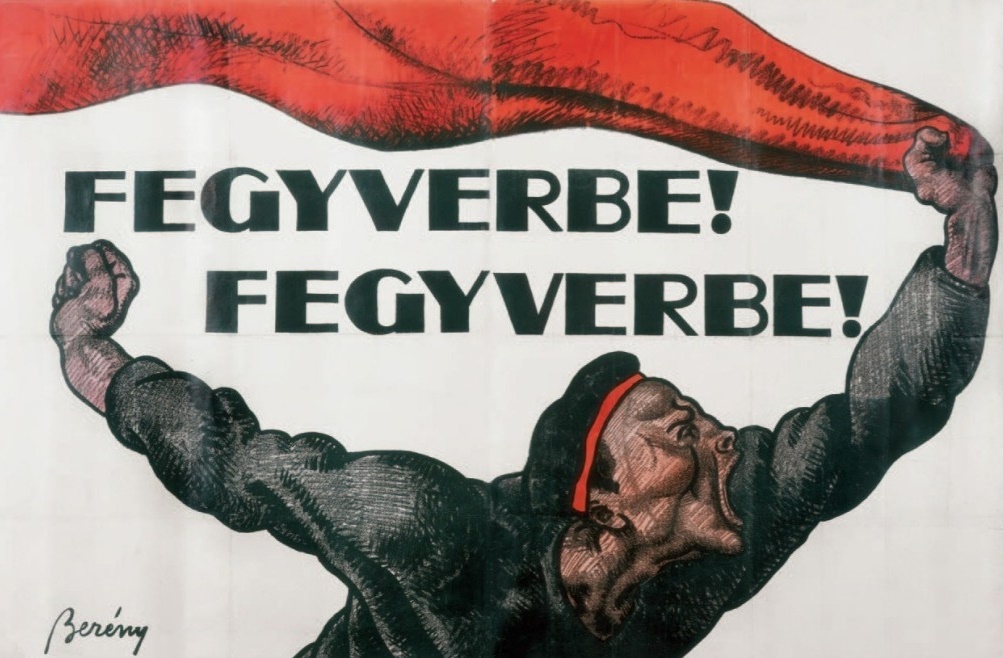

By Cain O’Mahony – the last in a series of three articles. Part I can be found here, and Part two here. [Main photo – “To the Front” – Hungarian revolutionary poster]

*****

Béla Kun’s ultra-leftism convinced him that the Russian Revolution had been ‘too timid’, and he was determined to establish ‘socialism’ from above, without reference to the real balance of class forces in Hungary, or the lessons of the Russian Revolution. Kun was in a hurry.

The first serious mistake was to miss the opportunity for a breathing space, to build support. The western allies had been shocked by Karolyi’s handing over of power to the ‘Bolsheviks’, and backed off somewhat, fearful of pushing Hungary over the edge into full blown revolution (as opposed to the current ‘little cats’ feet’). They made the offer to withdraw all military forces to the military demarcation lines that had been agreed in the Armistice in November i.e. out of the currently occupied areas. It was Kun’s Brest-Litovsk moment, to ‘gain time’.

Yet Kun refused to agree. He was on the march for Bukharin’s international revolutionary war, with no stopping or turning. Initially this proved a military disaster and robbed the fledgling revolution of a valuable breathing space. Snubbed, the proxy armies of the Western allies continued their advance.

Kun meanwhile blundered on. The greatest error, which would prove fatal in the long term, was to make a complete mess of the agrarian revolution.

In the Russian Revolution, the Bolsheviks had immediately redistributed the land to the peasants. In Russia, only 10 per cent of the population were working class, and the Bolsheviks knew that to defend the gains of October, they needed the mass of peasants on their side. They knew the immediate collectivisation of the land would cause confusion amongst the peasantry, and time was needed to win them over to this policy – time the Bolsheviks didn’t presently have. But for the moment, the peasants would fight to defend their precious parcel of land and defend the revolution that gave it to them.

Hungarian Revolutionary Poster (Arpad Bardosz)

Land nationalisation

But Kun shunned this tactic. He was in a hurry, and short cuts were the order of the day. The peasant classes had expected their home-grown Bolsheviks to follow the example of their Russian comrades. Instead, Kun nationalised all the land of the landowners – he did not turn them into collectivised co-operatives, but rather appointed ‘State Commissars’ to manage these new ‘nationalised’ estates. And who were the new ‘Commissars’? Those who had the experience to do so – the vast majority were the original landowners and bailiffs!

For the peasant classes, nothing changed: Kun had “… managed to combine the worst of both worlds: stoking fear in the wealthy peasants and alienating the poor peasants… Hungarian agriculture under the Soviet Republic was simply the old order painted a light shade of red” (Doug Enaa Greene, Lenin’s Boys: a short history of Soviet Hungary, 2020).

The mistakes were mounting. As the former Austrian revolutionary Franz Borkenau would later sarcastically remark:

“In Russia, Kun had seen there things which were of primary importance for a Hungarian revolutionary: the agrarian revolution; Lenin’s fierce fight against the ‘reformists’; and the peace negotiations with the Germans at Brest-Litovsk.

“From these three experiences, Kun seems to have drawn the surprising principles: that one must not give the land to the peasants; that one must make war at any price; and that, at the decisive moment, a revolutionary must form an alliance with the reformists” (World Communism, 1938).

Kun’s approach to the economy was equally chaotic. In the Russian Revolution, the Bolsheviks had initially seized the banks and finance houses only, to prevent an immediate flight of capital, and have some levers over the existing capitalist economy. They knew the immediate nationalisation of industry without any worked-out plan of production would cause economic dislocation at a time of revolutionary civil war. When the revolution was secured would be the time to consolidate the socialisation of the economy.

Not so Kun. He thought he could ‘improve’ upon the Bolshevik’s cautious approach. With no worked out plan in place, instead the young Soviet Republic nationalised all companies employing more than 20 employees. In less than a month, 27,000 enterprises had been nationalised. As Greene comments:

“This crash course in nationalisation would have been a heroic undertaking in an advanced capitalist country, but Hungary was not only a backward one, but it faced economic collapse and possessed no planning infrastructure to integrate the industries.”

Edge of defeat

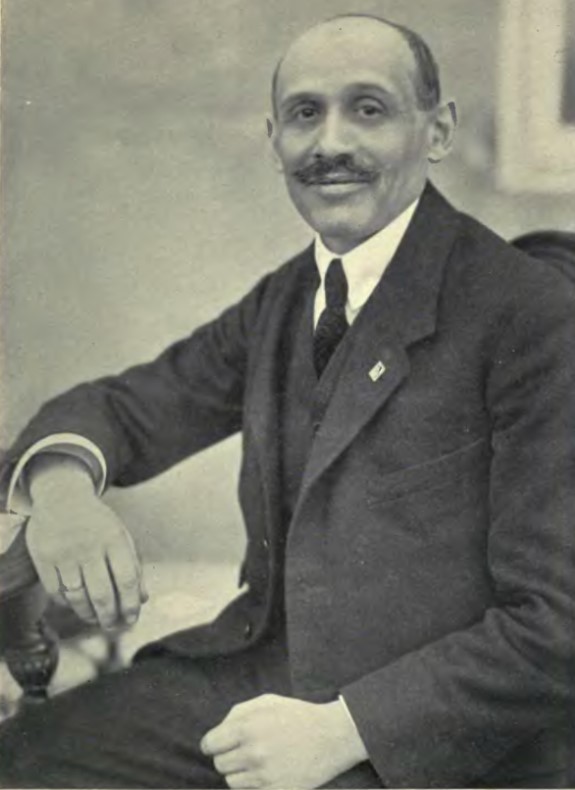

With the armies of the Western Allies’ proxies, Romania and Czechoslovakia, steadily advancing on Budapest, the Soviet Republic looked on the edge of defeat. Kun soon learnt the cost of the KMP being in a minority in an SDP dominated government. They sidestepped Kun and installed one of the ‘heroes’ of the Aster Revolution, the trade union leader Vilmos Bohm, as head of the Hungarian ‘Red Army’. Although a former Engineer Socialist, Bohm was on a right-wing trajectory, and his solution was to reinstall the old officers from the former imperial regime, most of them from the landowning classes. This brought a semblance of organisation and structure, but would be at a future cost.

Vilmos Böhm (1880-1949)

Commander-in-Chief of the Hungarian Red Army

Kun, to his credit, meanwhile, went direct to the workers to swell the Red Army’s ranks. The day after the 1919 May Day celebrations, he took his appeal to the Budapest Workers Council. There was a magnificent response. The Steelworkers Union agreed to defend Budapest, and factory workers across the city flocked to join up – soon, nearly 200,000 workers were under arms, and they marched on the invaders.

But this demonstrates the ‘dual running’ of the Soviet Republic – on the one hand, the KMP taking the revolutionary road, but on the other, the SDP reformist out-flanking them and returning to the old bourgeois state structures and mentality.

That aside, the new Red Army defeated the Czechs and pushed the Romanians back to the border. As Greene puts it: “The workers’ revolutionary flair translated into victories on the battlefield”.

But despite the victories, the national question came back to haunt them. The various ethnic groups were not dealt with adequately. The Soviet Republic put on an internationalist face, outlawing national and racial oppression in its new constitution. But it was a case of ‘some ethnic groups being more equal than others’, with ‘Magyar chauvinism’ still prominent amongst the leadership of the former SDP. So while ethnic Germans were granted cultural autonomy, it was refused to the Croats and Transylvanians, the latter being dismissed as ‘hirelings of Romanian boyars’.

Hungarian chauvinism

Unfortunately, Hungarian chauvinism was bolstered further – ironically – by the initial success of the reformed Hungarian Red Army.

In June they advanced into Czechoslovakia, and established the Slovakian Soviet Republic. Many progressive reforms were imposed, but there was a general suspicion by the Slovakian masses that it was a Hungarian imposed ‘revolution’, rather than a home-grown one. Meanwhile, nationalist elements amongst the bourgeois officers now leading the Red Army began to whip up dissent about the ‘betrayal’ of Kun in not re-establishing ‘Upper Hungary’, but instead handing the territory over to Slovakia.

The Western Allies at the same time were furious at the Hungarian threat to Wilson’s ideal of a white bulwark against Soviet Russia. They demanded the Hungarian Red Army withdraw from Slovakia, in exchange for Romania withdrawing from Hungarian territories. Having had his fingers burnt in turning down the previous offer, this time Kun decided to emulate Lenin over Brest-Litovsk.

But this time, it was the wrong time to stop. Kun walked into a trap. He had snubbed the Western Allies the first time around, so they did not feel in the least bit bound to honour their offer. As the Red Army withdrew from Slovakia, the Romanian Army continued to advance on Budapest. Soldiers began to desert from the Hungarian Red Army in droves, confused at this ‘betrayal’.

The authority of the Soviet Republic began to crumble. Back home, precisely because Kun had built the KMP not on the disciplined democratic centralist model of the Bolsheviks but instead a loose alliance of all-comers, and one submerged within the social democracy, party discipline broke down.

Self-appointed paramilitary groups such as Tibor Szamuely’s ‘Lenin’s Boys’ substituted themselves for mass action, and began trying to impose socialism at gunpoint, attacking the peasantry – only emboldening their hostility towards the revolution – and terrorising SDP leaders.

The SDP feared a coup against them by the KMP and prepared to respond, only to discover that the KMP were carrying out a coup against a resurgent anarchist movement. With the Romanian Army now at the gates of Budapest, everything disintegrated; panic ensued and the leaders of the revolution fled.

Kun blames the workers

Kun gave a demonstration of a key flaw of ultra-leftism: when their adventures or false policies fail, they blame not themselves but the workers. In a curtain call to the Hungarian revolution as he fled for Vienna, Kun declared:

“The Hungarian proletariat betrayed not their leaders but itself… If there had been in Hungary a proletariat with the consciousness of the dictatorship of the proletariat it would not collapse in this way” (Rudolf R. Tőkés, Béla Kun and the Hungarian Soviet Republic: The Origins and Role of the Communist Party of Hungary in the Revolution of 1918–1919, 1967).

After the collapse of the Soviet Republic, the Western Allies unleashed the Hungarian White Army led by Admiral Horthy, backed by the French and Romanian military. Between 6,000 – 10,000 were murdered in the White Terror that followed – in Budapest, given that many leaders of the revolution like Kun or Vilmos Bohm were Jewish, it took on the form of an antisemitic pogrom.

“Regent” (ie dictator) of Hungary (1920-1944)

Bela Kun meanwhile, as the Stalinist bureaucracy began to take over the Bolsheviks, found his Left Communism in tune with Stalin’s growing ultra-left ‘Third Periodism’, and he rose up the ranks, unfortunately also bringing his mis-leadership into the failed German revolution.

Kun was favoured by Stalin until the latter’s 180 degree turn to right wing Popular Frontism, and the ultra-left Kun could not adapt speedily enough, and he was executed in the purges of 1937/38.

In mitigation for Kun and the KMP, it is easy to criticize with the ‘genius of hindsight’. Kun and his followers were young and inexperienced, unlike the old Bolsheviks who had the lessons of both the 1905 and 1917 revolutions to draw upon. Also, like many at the time Kun was convinced the spark of revolution would spread rapidly – the Bavarian Soviet Republic had been declared, and both Germany and Austria were on the brink, all of which would come to the aid of both Russia and Hungary. Hence, Kun was gripped by an urgency to deliver.

Abject lesson in ultra-leftism

However, the episode is an abject lesson in ultra-leftism, of moving in advance of the class and not adapting to the reality around you, and the dangers of betraying class politics by the temptation of opportunism and popularism.

There are political lessons for us today too, albeit on a far smaller scale. To an extent, the leadership victory by Jeremy Corbyn came to us on ‘little cat’s feet’ – it was not the result of a systematic, organised mass campaign by the rank and file of the Labour Party, but a tactical blunder by the right wing. It was still a massive victory , and the mass of workers who flooded into the party in support indicated this. But these mainly young new Labour Party members were inexperienced – enthusiasm is no substitute for experience.

Meanwhile, there was no organised, disciplined tendency united around an agreed socialist programme to greet and organise them. There were some admirable attempts to do this, but we were always playing catch-up, and Labour’s right wing with the backing of all the forces of the establishment ran rings around us, precisely because we were not prepared for this sharp turn of events.

We must make sure that opportunities are not missed again, and start organising for the future now.

***********

Footnote: for those of you who like the quirks of history, there are two other legacies from the failed Hungarian revolution, which fortunately had happier endings.

- The leading activist in the Hungarian Actor’s Union who had played a major part in the programme of nationalising theatres, escaped and eventually made it to Hollywood to begin a new career. His name was Bela Lugosi – famous in the role of Dracula.

- Meanwhile, Nicholas Kove, who like Béla Kun was recruited to the cause of revolution while a PoW in Russia in 1917, rose up the ranks to become a junior Minister in the Soviet government. He too escaped and eventually settled in London where he began experimenting with plastic moulding. He designed and mass-produced plastic combs, replacing the expensive metal ones that workers could not afford, and the wooden ones that easily broke. His next venture would be to the future delight of generations of post-war children (including me), launching his new company after World War II. It was called Airfix.