Andy Ford (Warrington South Labour member) continues his occasional series of articles on the history of WW2 in the Soviet Union.

*****

The Nazi siege of Leningrad was finally lifted on 26th January 1944. Despite this final success, it was very much a bitter victory with millions of civilians dead in the most horrendous circumstances, and hundreds of thousands of Red army soldiers killed and wounded.

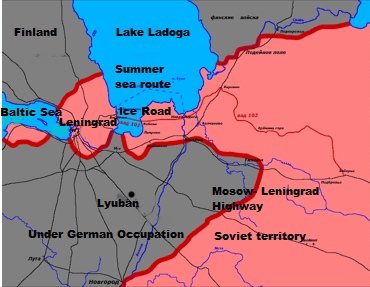

Repeated military operations to get through to the encircled city had been some of the most incompetent and costly ever carried out by the Stalinist high command. They were partly driven by desperation, as hundreds of thousands of civilians were starving in Leningrad, and also by frustration, as the horrific siege was only maintained by German occupation of a strip of occupied territory which at some points was less than 10 miles across (see map in featured image).

Hitler aimed at nothing less than the extermination of the population, declaring that “Petersburg, that poisonous nest from which, for so long, Asiatic venom has spewed into the Baltic – must vanish from the earth’s surface. The city is already cut off. It only remains for us to bomb and bombard it, and destroy its sources of water and power, and then deny the population everything it needs to survive.” One of his advisors, Professor Ernst Ziegelmeyer of the Munich Institute of Nutrition, had worked out that on 250g of bread a day, “The Leningraders will die anyway. It is essential to let not a single person through our front line…they will die, and then we will enter the city without trouble and without losing a single German soldier.”

In the first attempt at lifting the siege, the ‘Battle of Lyuban’, from January to April 1942, the Red Army launched a huge infantry attack towards Lyuban in German-occupied territory. The aim was to cut off the base of the strip and encircle the occupiers in its northern portion. Tanks could not be used because of the marshy terrain, but that meant that the Red Army troops were vulnerable to fire from the well-prepared German strongpoints.

Catastrophe

After a strong initial penetration of the German frontline, the Soviet 2nd Shock Army was surrounded and destroyed, and its commander, Andrey Vlasov, captured. Of the 325,000 men committed, 308,000 ended up killed, captured, missing, or wounded. Even by the standards of the Stalinist military ineptitude of the first half of the German invasion, it was a catastrophe.

Next, in August 1942 the Soviets threw their forces in a full-frontal assault on well-prepared German positions on the low hills around Sinyavino, south of Lake Ladoga. What they did not know was that the Germans were simultaneously massing for an assault on the city. The fall of Sevastopol in July 1942 had freed up hundreds of thousands of Wehrmacht soldiers who could be switched from the Crimea to Leningrad. Despite this, initially the Red Army made good progress, and at one point were only 4 miles from reaching the Russian lines around Leningrad.

But ultimately, the Germans were able to use the troops assembled for their offensive to first block and then push the Red Army back. Matters were not helped by the inexplicable Russian failure to co-ordinate the breakout from Leningrad with the inward attack of the relieving forces towards the starving city. By October the Germans had re-established most of their siege positions. But their forces had been severely mauled, and the German High Command was forced to order them over to the defence.

Finally, with ‘Operation Iskra’, in January 1943 the Soviets cleared the Germans from the southern shores of Lake Ladoga, so technically breaking the siege. But it came at a cost – 34,000 Russian soldiers were killed in the battle, with German losses of 12,000 killed and 35,000 wounded. But transport across the forests and marshes of the captured area was difficult, with few roads, and even with the immediate construction of a railway to get supplies through, it was never enough.

By January 1944 the Nazi besiegers had been seriously weakened by troop transfers required to deal with the defeats at Stalingrad and Kursk, and Hitler’s generals proposed withdrawal to a shorter and more defendable line. But Hitler refused to lift the siege and simply told them to hold on to every metre of territory.

Siege over

Sure enough, on January 14th, Soviet forces attacked from out of the besieged city, reinforced by men and material transported across the ice of Lake Ladoga on the ‘Road of Life’. At the same time the Russian Volkhov Front attacked from outside, beginning with a huge artillery barrage of 220,000 shells onto the German lines. The Nazi formations were in no condition to repel a determined and co-ordinated assault and by January 26th the Germans had been pushed back 60 miles. The main Moscow-Leningrad railway was now in Russian hands and food supplies could at last flow freely. By February 15th the Red Army stood at the borders of Estonia where the Germans stabilised a defence around Lake Peipus. The siege was over.

Stalin ordered victory celebrations and a 21-gun salute, but it can hardly have felt like a victory – of the pre-war population of 3.1 million, only 700,000 people remained, of whom half were soldiers or sailors. “We brought out vodka,” a teacher wrote of the victory celebrations. “We sang, cried and laughed. But it was sad all the same — the losses were just too big. A great work had ended, impossible deeds had been done, we all felt that… But we also felt confusion. How should we live now?”

by the surviving Leningrad population

Soviet sources state that 498,000 people were evacuated before the siege started, and 660,000 evacuated over the ice in the winter of 1941/42 – 35,000 by plane, 33,000 by boat before Lake Ladoga froze in November 1941, 36,000 in “unorganised vehicles”, and 554,000 in the official “organised” convoys across the ice. Another 1.2 million, including many children, were evacuated over the remainder of 1942 and 1943.

But around 1.3 million died of disease and starvation, especially children and the old. Rations in besieged Leningrad were very closely matched to the work that people did. So, at the start soldiers, sailors and marines, and industrial workers got 600g of bread daily, and for those not working, like the retired, or refugees, it was 300g. Later, those quantities had to be halved. Starvation was the inevitable result. But submission to the Nazis was never an option; the invaders were under orders to accept no surrenders, and to destroy the city and annihilate its citizens. But Leningrad endured; and that was the closest thing to a victory that was possible in the circumstances.

Hitler hated Leningrad with a passion because it was the cradle of the Russian Revolution which had offered the world a future without poverty, war, racism, or unemployment. In the course of the 20th century the working class of Leningrad was decimated time after time; first during the Civil War when the workers and sailors of ‘Petrograd’ fought off the 21 armies of imperialism; then by Stalin’s insane purges of the 1930s which fell especially heavily on the city; and finally, by Hitler’s barbaric siege. These successive events physically destroyed the memory of October 1917 with tragic results for later Russian history.