Andy Ford (Warrington South Labour Member) continues his occasional series on the 80th anniversaries of WW2 for the Soviet Union.

*****

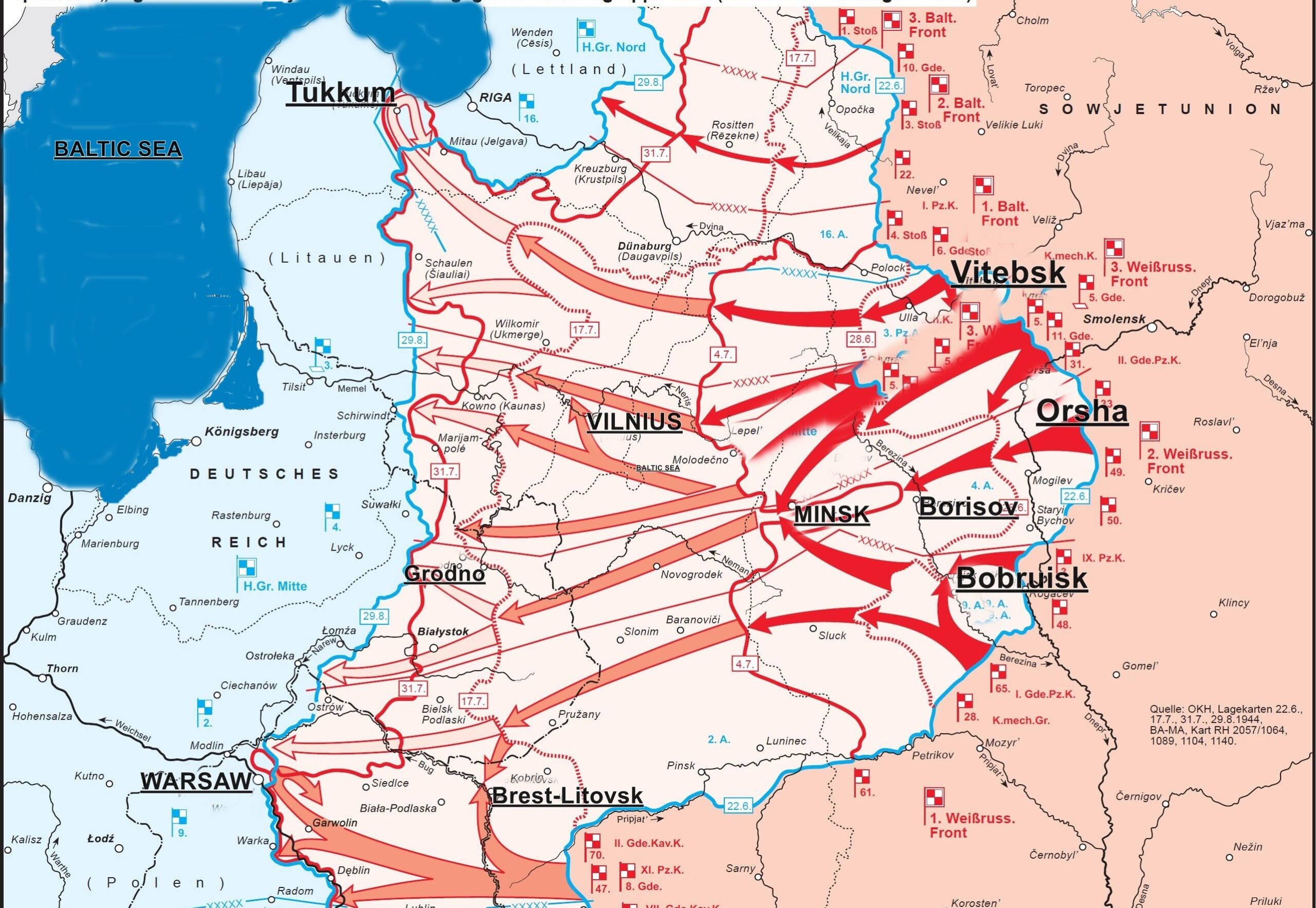

On 22nd June, 1944, almost 3 years to the day since the sudden Nazi attack on the Soviet Union, the Red Army unleashed an enormous offensive against Army Group Centre of the German Army on the Eastern Front.

When it began, the Nazis were still deep within the Soviet frontiers, occupying more or less the whole of Byelorussia. When it ended their forces had been thrown back 500 miles, into Lithuania and Poland, and 350,000 German soldiers had been killed, or were missing or captured. It was the biggest Nazi defeat of the whole war. By contrast, the Battle of the Falaise Pocket, which was the decisive engagement of D-Day, cost the Germans maybe one seventh that number of casualties.

To the south, the Soviet victories across Ukraine earlier in 1944, and to the north the lifting of the siege of Leningrad in January and February 1944, had left Army Group Centre occupying a salient projecting into Soviet territory extending from Vitebsk to the Pripyat Marshes. It was the obvious place for the Russians to attack, but Hitler had decided – and insisted – that the Soviets would continue their progress in Ukraine.

He was increasingly resorting to wishful thinking and had persuaded himself that a stunning reversal was possible by allowing the Russians to attack towards Germany from Ukraine, and then encircling and annihilating their armies. As he had by now surrounded himself with spineless sycophants, no-one dared disagree, and so the few reserves that were available, were sent to Army Group North Ukraine.

Enfeebled

This left Army Group Centre in an enfeebled state: the frontline troops were very spread out, with each kilometre of the line held by just 80 soldiers; the biggest group of tanks was only 40 strong with 240 assault guns across the whole army group; and they only had 66 fighter planes assigned. The 300 bombers they had were not really usable without fighter cover.

The Russians knew the weakness of their Nazi opponents and planned for a massive encirclement of the German forces occupying Byelorussia, ending with the liberation of the capital Minsk, in what was like 1941 in reverse. But they also set up an elaborate deception in Ukraine, even constructing a dummy army near Kishiniev and deliberately allowing German reconnaissance planes to see and photograph it.

Meanwhile 100 trains a day delivered war material to the forces lined up against Byelorussia and a huge array of 12,000 American Studebaker trucks, supplied under Lend-lease, would make the Red Army more mobile than ever before. Soviet tank production continued to outstrip Germany’s: they had 2,700 tanks and 1,135 assault guns, an advantage of about six to one. The Red Air Force (VVS) deployed 2,000 fighters and 1,000 ground attack aircraft, mainly the formidable Ilyushin-2 ‘Sturmovnik’. They had also prepared 290,000 hospital beds.

The Red Army also possessed an important auxiliary arm in the Soviet partisans, who numbered 170,000 armed men, organised in 157 brigades and 83 detachments. By 1944 they controlled vast swathes of the Byelorussian countryside, with the Germans confined to the cities and main towns. They could not take on the main Nazi forces in open battle, but they could sabotage roads, bridges and railways, interrupt reinforcements and harass retreating German formations, and pass valuable intelligence to the Red Army and Airforce.

Vitebsk: first move

The partisans began the battle on the night of 19th/20th June, placing 14,000 explosive charges on the railways, putting the Byelorussian network out of use for a full 24 hours. On June 22nd the Red Army made raids on the German lines to test their defences and then, at dawn on 23rd June a huge artillery barrage opened attacks north and south of the city of Vitebsk. The Red Army tactics were far superior to the massed infantry charges of 1942/43; now they sent in an advance guard to seize high ground, and then used that to cover the main advance.

The German command requested reinforcements, which were denied, as the Wehrmacht followed Hitler’s proclamation that the main attack would be from Ukraine. They were also denied retreat as Hitler designated Vitebsk as a ‘Fester Platze’ or ‘fortress city’, to be held at all costs. The result was complete encirclement of 40,000 troops.

On the night of 26th June, the besieged troops attempted a breakout. The last message was received at 03.45 on 26th June requesting the position of the closest German units. It was the last message received. The Germans now broke up into battalion-size units and attempted to flee across countryside controlled by Soviet partisans, who had little inclination to take prisoners. The army of 40,000 men disappeared.

Breakthrough at Orsha

At the same time as commencing operations around Vitebsk, the Red Army’s strongest tank formation, 5th Guards Tank Army, attacked at Orsha to the south along the main highway from Moscow to Minsk.

Hitler designated Orsha as yet another ‘fortress city’, instructing the defenders to hold on to the death. Reinforcements were requested, and denied, leaving them in an impossible position. The local commander, General von Tippelkirsch, defied orders and withdrew most of his troops, leaving a token force in the ‘fortress’. Orsha fell on the night of 26th June, opening the main road to Minsk. The Red Army rushed forwards towards the River Berezina, which was the final barrier between them and Minsk, the Byelorussian capital; simultaneously the Germans tried to create a defensive line on the river.

When German reinforcements arrived at Borisov, the main crossing of the Berezina (and the site of a major battle in Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow), they were greeted by a chaotic scene. Huge numbers of German troops were fleeing across the bridges over the Berezina, many isolated from their units and without weapons. Wrecked vehicles and abandoned weapons lay everywhere as the retreating columns had been unprotected from the Red Air Force. Nevertheless, they did establish a strong defence at the bridges.

The Russians then attempted crossings of the river north and south of Borisov eventually finding a way through swamps north-west of the city. Another Russian force crossed by driving tanks into the river to form a crude bridge or steppingstones for the infantry to cross., and a further force crossed south of Borisov, overcoming a weak German defensive line on the western bank. Borisov was now almost surrounded, and the Germans fled after heavy street fighting. The main road to Minsk now lay open to Soviet armour.

Bobruisk: another Nazi defeat

The Red Army planned a further encirclement by approaching Minsk from the south, through the town of Bobruisk. At first the Russians made slow progress due to the swampy ground, but on 24th June the Russians began to break through and forced the Germans to retreat to Bobruisk. The German commander, Field Marshal Busch flew to Hitler in Obersalzburg, hoping to persuade him to permit an orderly withdrawal; Hitler’s response was to dismiss him from command.

The result was 40,000 troops trapped in Bobruisk. They made successive attempts to break out, each of which degenerated into a shambles. Finally, 5,000 Germans broke through a thin Soviet infantry cordon, opening the way for maybe 15,000 to flee to Minsk, where they arrived without weapons, vehicles, or heavy equipment. 3,500 wounded were left behind in the town’s citadel. The town finally fell on 29th June, opening the way to the total encirclement of all German troops in Byelorussia.

The liberation of Minsk

Despite the impending disaster, reinforcements were scarce as the German High Command still had to keep large forces in NW Ukraine to stop the Russians striking into Romania and cutting off the Nazi’s only source of oil, the Ploesti oil fields. By 8th July the leading Panzer division had been reduced from 128 tanks to just 18, and the approaches to Minsk were held by a motley collection of units that had survived previous battles.

Photo by W. Suchodolski, August 1944.

The Red Army was converging on Minsk from three directions: from Bobruisk in the south, facing almost no opposition; from the east, down the Moscow-Minsk highway; and from Vitebsk in the north-west through thick forest. The German strategy was a desperate one – to keep the railway line from Minsk to the west open long enough to evacuate the wounded, the Nazi administrative and political staff, plus frontline troops if possible.

But by the 3rd and 4th July the Red Army had sealed their encirclement, leaving the Germans facing a disastrous defeat. Only 1,800 organised troops remained to defend Minsk, while another 15,000 unarmed stragglers milled around the city, ironically designated a ‘fortress city’ by Hitler. A further 8,000 wounded and 12,000 administrative and security troops faced capture by the Red Army.

Tens of thousands more German soldiers were trapped in other pockets scattered across Byelorussia. As their food and ammunition dwindled, they were forced to try and sneak through the countryside back to the German line – across countryside controlled by partisans, the same partisans they had spent two years persecuting with punitive expeditions, mass hangings and starvation. As a result, the fate of captured German units was usually not a pleasant one, and the best estimate is that of the 15,000 that set off, only 900 reached German occupied territory.

57,000 prisoners were paraded through Moscow on July 17th, sometimes known as the ‘parade of the vanquished’. Although the Stalinist officials may have hoped for hostility and abuse from the population, the British journalist Alexander Werth reported that the Muscovites just stared in silence at the bedraggled procession of starved and demoralised Germans, some with tears in their eyes, and that any youths who shouted insults were shut down by the adults. One woman commented, “Just like our poor boys”, and a child simply asked, “Are these the men who killed Daddy?”.

The troops liberating Byelorussia had no such feelings. As they pushed west, they found something equivalent to the damage of a nuclear bomb – burnt villages, towns without a public building left standing, demolished hospitals, destroyed crops and mass graves. Hundreds of thousands of Jews had been shot by the SS death squads or deported to Auschwitz and thousands of civilians killed in the course of collective punishments.

Werth reported on a mass grave of 2,500 civilians discovered in the town of Zhlobin, and crops ploughed under, or flattened by special tractors. It was devastation, and it is estimated that 25% of the population of Byelorussia perished during the 4 years of brutal occupation.

Westwards

The huge success of Bagration, surpassing all expectations, allowed the Soviet high command (STAVKA) to set further objectives. The Russian forces pushed further west to liberate Grodno, Brest-Litovsk and Vilna (modern day Vilnius), even reaching the Baltic Sea at Tukkum in Latvia on 31st July, so cutting the entire German front in two. The furthest west they reached was the eastern bank of the Vistula, opposite Warsaw, towards the end of July.

The political aftershocks

The political effects of Bagration were huge. It was after all, the biggest defeat of the German armies in the whole war. The German High Command (OKW) official record stated that it was “a greater catastrophe than Stalingrad”. A whole Army Group, not just one army, disappeared from the German order of battle. Romania changed sides in August, and Finland was out of the war by September.

The Red Army presence on the Vistula triggered the Warsaw uprising, with all its tragic consequences. And the unfolding defeat in Russia undoubtedly played a part in the decision by the German officer corps to attempt the assassination of Hitler on July 20th. They were infuriated by his idiotic strategy of ‘fortress cities’ – which probably doubled or tripled German losses – and by his amateur strategizing which amounted to not much more than drawing lines of the map and wishful thinking. Everyone knew that Nazi Germany was doomed.