The failures of communism, by Cain O’Mahoney

Following the neglect of the Bulgarian Communist Party (BCP) to build a base among the peasantry and their inactivity after the fascist coup of 1923, the BCP was eventually stung into a response by the criticisms of the Communist International. [The is the second part of a two-part article, the first is here]

The Comintern had fumed at the BCP’s naivety; for all their doctrinaire studies of Marxism, they had not learnt the simplest of lessons of the Russian October Revolution. As Zinoviev had urged them after the coup: “Now we must ally ourselves with the accursed Stamboliiski. The Bolshevists fought with Kerensky against Kornilov” ( International Press Correspondence, 28 June 1923).

It was by now far too late, but the BCP belatedly staged an uprising, the first anti-fascist uprising of the era, in September 1923. As predicted, the fascists had already turned on the communists as soon as they seized power, and before the communist uprising could get underway 2,000 of their cadres were murdered or imprisoned, mainly in their industrial strongholds. This meant that the uprising was confined to rural areas, while little, if any, action was taken in the cities and towns, which would have been vital for success.

Anti-fascist uprising only partially successful

The BCP, rapidly now belatedly trying to build a united front with the left wing of BANU, the main peasant party that had formerly held the majority before the fascist coup, as well as the anarchists. They staged an anti-fascist uprising with initial success in the Stava Plania mountain range, but this proved to be only temporary.

With the peasants already crushed, and the BCP, after years of ‘peaceful propaganda’ work, totally unprepared for an armed revolution, they were easily defeated, and thousands of communists paid for the errors with their lives.

The repression was vicious. The most atrocious incident followed the battle for the mountain railway station at Lakatnik. The fascists won, but did not waste bullets on the rebel prisoners, and instead threw hundreds to their deaths over the sheer cliffs that surrounded the station.

The BCP was decimated, but those who survived fled to the mountains to join those peasants still fighting, and a small scale civil war effectively continued in rural areas right up until Bulgaria’ liberation from Nazism by the Red Army in 1944. For Bulgaria, the ‘Second World War’ effectively began in 1923.

One advantage gained by the original ill-fated uprising was that it won large swathes of the peasantry to the BCP, especially now that the BCP had corrected its main slogan to ‘For a Workers and Peasants Government’. The fascists could not fully crush the revolt, and large swathes of the remoter areas of the countryside remained under BCP and BANU control.

Bulgarian communism increasingly peasant-based

As Zinoviev described it: “The peasantry blockades the capital, refuses to supply food. The peasant youth plunges into the struggle. But – there are no weapons. Adversaries armed to the teeth have almost to be fought with bare fists. Stamboliiski was simple-minded enough to leave the peasantry unarmed” (Zinoviev, The Import of Events in Bulgaria, 18 October, 1923).

However, cut off from their former industrial base, the BCP – increasingly influenced by the peasant movements – swung 180 degrees from ‘doctrinaire’ passivity, to ultra-left guerillaism.

The most bloody episode of this ongoing war was the attack on the St Nedelyn Cathedral in April 1925. BCP members wanted to bomb the funeral of a government minister who had been assassinated, and they approached the Comintern for permission. The Comintern replied that it would only be ‘acceptable’ if it was part of a new mass uprising, otherwise it would be no more than an act of individual terrorism.

The BCP went ahead anyway, and the ensuing explosions killed 140 people and injured a further 500. The Comintern were of course right – some leading fascist figures were killed, but they were soon replaced, and the repression only intensified as the regime now had a new ‘excuse’, since the mass murder alienated those followers of the Orthodox Church, who were appalled at such ‘sacrilege’. It takes mass action to bring down fascist regimes and the capitalism system, not individuals planting bombs.

In this ferment and political confusion, the followers of Leon Trotsky began to build a base. A key player was Dimitev Gatchev. A member of the Spartakus Bund in Germany in 1921, he was sent to Bulgaria by the Comintern to reorganise the BCP after their defeat in 1923.

Left Opposition gained a small but influential foothold

As news spread of the growing confrontation between the bureaucratic tendency around Stalin and the Left Opposition around Trotsky, Gatchev joined the Left Opposition in 1925. The Bulgarian Trotskyists built a small but increasingly influential group within the BCP, with their journal, Liberation, building a circulation amongst BCP members of around a thousand.

But a two-pronged attack effectively liquidated the Trotskyists for a period. This was firstly because Stalin and his placemen increased their grip across all of the communist parties internationally, and as a result the Trotskyists in the BCP were persecuted and driven out.

But then also came a new coup in Bulgaria by the fascists. Tsar Boris III had managed to wrest back a semblance of parliamentary democracy from the original coup in 1923, and BANU was able to return at the head of a pro-democratic coalition government. However, in 1934, militarists based around the Zveno nationalist movement, once again staged a coup, establishing a dictatorship and rounding up all opponents, including the BCP, Stalinists and Trotskyists alike.

As RJ Alexander wrote, “… the regime’s police did not make nice distinctions between Stalinist and Trotskyist Communists. They were herded indiscriminately into the same prison compounds… In prison there were riots between Stalinists and Trotskyists, and the latter being fewer got the worst of these clashes” (International Trotskyism 1929 – 1985: A documented analysis of the movement, Robert J Alexander).

Bulgaria freed from Nazis by the Red Army and Bulgarian partisans

The removal of the Trotskyists meant Stalinism became entrenched in Bulgarian communism and Trotskyism would not re-emerge as a political force until liberation in 1944. For most of the Second World War, the remaining Trotskyists were either in prison or in hiding. The liberation of Bulgaria by the ‘Fatherland Front’ partisans and the Red Army in Septmber 1944, saw release for many who had been either imprisoned or driven underground, including Gatchev.

The Bulgarian Trotskyists reorganised and produced a journal, Communist Appeal, opposing the Fatherland Front. The entrenched Stalinism of the BCP – now calling themselves the Bulgarian Workers’ Party – can be seen by their setting up of a ‘Popular Front’ ‘resistance’ organisation, long before the orders to do so came from Moscow. In the early dark days before the victory at Stalingrad and the turning of the tide against the Nazis, many rank and file communist resistance fighters were cut off from the party line from Moscow, and some began to independently move towards revolutionary class policies, the beginning of which was seen in Slovakia, Greece and Yugoslavia. Not so in Bulgaria.

Early in 1942, the BWP formed the Fatherland Front, made up of themselves, BANU and – incredibly – even the far-right Zveno militarists who had led the coup in 1934. The Social Democrats joined the Fatherland Front the following year, and the Stalinist-dominated Front took power in 1944 (see From Nazi ally to enemy in a week: Bulgaria – September 1944, Andy Ford).

New Stalinist rulers brooked no opposition

The Trotskyist Communist Appeal group opposed this Popular Front model, warning of the dangers of having the likes of Zveno in the ranks, something which could pave the way for the return of reaction, and they began to build support amongst revolutionary workers. As the Fourth International (the international organisation formed by Trotsky before his assassination) reported:

“During the last months our Bulgarian party has carried out a very great activity. It launched, through its paper and public demonstrations, the slogan of a ‘Workers and Peasants Government’ and appealed energetically to the Bulgarian Workers Party for a united front against reaction” (US Militant, 31 August 1946).

After the defeat of the Nazis by the Red Army, the new Stalinist rulers would of course not tolerate such independent revolutionary thought, and the purge came in the summer of 1946, with the arrest of Gatchev and other leading Trotskyists including Mintho Telbizov and Liliana Pirintcheva. They were accused of the ridiculous charge of ‘organising a fascist coup’. Gatchev himself would remain in prison until the mid-1960s. The Trotskyist rank and file reformed themselves as the ‘International Communist Party’ to fight back, but they were soon liquidated.

The lesson of the failed 1923 anti-fascist uprising was that ‘theoretical purity’ is not enough to win the revolution – organisation, correct tactics of knowing when to advance and when to retreat, and a correct perspective, are all. As we have seen in the 1919-1923 period, revolutions were lost: in Austria because of illusions in left reformism, in Hungary because of ultra-leftism, and earlier in Ireland through sheer desperation. In Bulgaria, the revolution was lost because of theoretical dogmatism.

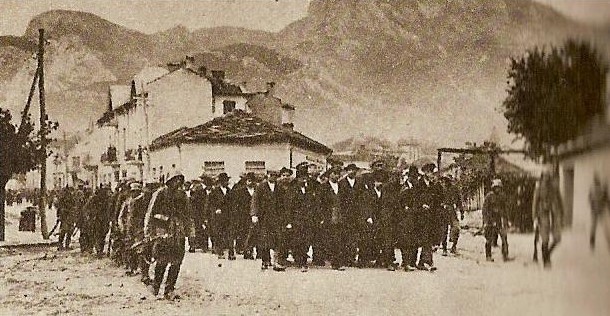

Top: It is 80 years, on 9 September, since the communist coup d’état which put an end to the Kingdom of Bulgaria. Picture from here.