By Michael Roberts

In part two of my report on the proceedings of ASSA 2025, I look at the sessions of radical economics organised by the Union of Radical Political Economics. I was unable to attend or link to any of these sessions, so this post is based on a review of the abstracts and papers submitted.

Unlike the mainstream sessions at ASSA, the issues around artificial intelligence (AI) did not appear in the radical sessions. Instead it was climate change, inflation, financialisation and imperialism.

Contributions on how to deal with climate change

On climate change, David Cayla of the University of Angers argued that the ecological transition from fossil fuels was less a matter of financial resources and more about allocating physical resources and human labour towards goods and services that may not provide immediate consumer gratification. How can we organize a new economic model, emphasizing ecological investment over consumer comfort, without necessarily resorting to global de-growth?

Organizing the climate transition in just a few decades could be compared to entering a war economy. This imposes serious constraints on the economy’s capacity to produce consumer goods and services. Cayla denied the need for any radical transformation of the social structure of capitalism because the war economies of WW2 showed that the market can function under constraining conditions. “Of course, it is always possible to imagine another economic system; however, even if achieving the ecological transition imposes enormous constraints on the economy, this does not mean that it is in itself, or by nature, incompatible with the market economy.” Really? All the recent works by eco-socialists compellingly show just that, in my view.

In another presentation, John Willoughby of the American University rejected Friedrich Engels idea that “economic life can be organized based on a democratic popular plan” as it “overly simplifies the complexity of economic organization and grievously misleads advocates of socialist organization.” Willoughby returns to the theory of ‘market socialism’ using market prices to allocate resources in a socialist economy. “Marx and Engels’ utopian vision rests on their inadequate appreciation of the complexity of planning, and their disdain for all the anti-social effects of market organization. While the latter is a compelling critique, it is one-sided and ultimately unconvincing. A regulated market will be an indispensable institution for a new socialist order in which workers are able to manage a greater part of their own affairs.” Hmm…

‘Digital labour’ and the race for critical minerals

Ali Alper Alemdar of St. Francis College looked at the profitability of ‘digital labour platforms’. He argued that platform workers are crucial to profitability, enabling higher fees, more potent network effects, and higher data accumulation, essential for expanding platform capital and achieving profitability. Indeed, platform capital is the backbone of profitability.

Debamanyu Das of the University of Massachusetts-Amherst argued that, as the energy transition advances, the stronger will be the need for critical minerals, leading to a race between countries for capturing these minerals. This was a new form of imperialism emerging. Core advanced nations (and China) are shifting focus from acquiring territories to acquiring mining corporations in peripheral countries, many of whom were formerly colonies of the imperial powers, resulting in the concentration of power in the hands of a select few multinational corporations.

Inflation and wages

Michele Naples of the College of New Jersey looked at the efficacy of the Keynesian theory of inflation supported by some in the mainstream discussion (see my post). Her study showed a strong negative impact of inflation on real wage growth. Inflation is always redistributive, it cannot create new value, only reallocate whatever real income there is. When inflation accelerates, the Fed intervenes to slow economic activity. This prevents workers from getting higher nominal wages. In 2021, when the Fed initially allowed price increases, it tightened credit conditions, claiming to prevent a wage-price spiral. Naples confirmed what many other studies have shown: namely that inflation predominantly increased profits and very little was accounted for by wage changes, contrary to Keynesian theory.

Bhavya Sinha of Colorado State University highlighted the trend of declining labour shares across countries and industries due to offshoring and subcontracting productive activities across borders. Exclusive rights to resources that are abundant in developed economies are protected via institutional arrangements but the labour force is increasingly subordinated to global capital. The share of value added thus continues to be weighted towards developed economies that not only protect exclusive rights on knowledge inputs through patents and copyrights but also influence the choice of technology in liberalized global markets.

The impact of globalisation on the labour share of value added

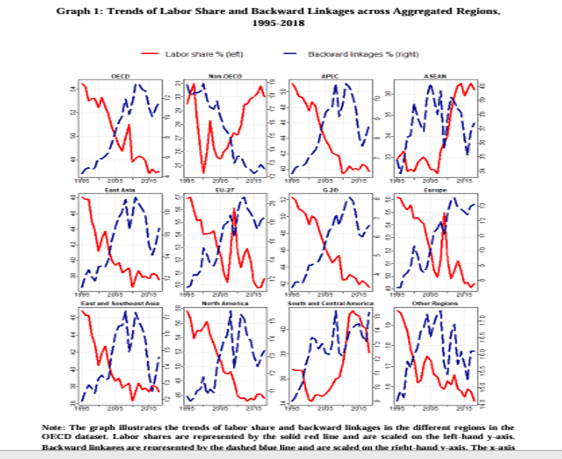

Sinha assessed the impact of this on the labour share in countries. He found parallel trends of rising foreign value added in gross exports, rising backward linkages in global value chains (GVCs) and declining labour shares across regions of the world over the period 1995-2018. So increased integration into GVCs was negatively associated with labour shares of value added.

This globalization of production extended the system of unequal exchange between industries and countries to between labour and capital within an industry across countries.

The need for an international response to climate change

On climate change, Robin Hahnel of the American University addressed the relationship between climate policies at different levels. No country can solve the problem of climate change on its own because reducing carbon emissions is a global public good which creates a perverse incentive for every country to attempt to ‘free ride’ (not reduce its own emissions), and instead wait to benefit when other countries reduce their emissions. Therefore, we need effective international cooperation.

Hahnel pointed out that only two countries were responsible for more than 10% of global carbon emissions in 2015 — China was responsible for 30% and the US was responsible for 15%. China emitted more than the US. But the population of the US was only 325 million in 2015, and the population of China was 1.4 billion – more than four times as large! Emissions per capita was only 7.7 tons in China, but was 16.1 tons in the US. And if we compare cumulative emissions from 1970–2015, the US ranks first, the countries that now comprise the European Union rank second and China is a distant third, even though China has a much larger population than either the US or the EU.

The problem of dealing with climate change is not that we do not know what solutions are – at the international, national, and state levels. The problem is not that we need to resort to untested technologies like carbon capture and storage or geoengineering. The problem is simply overcoming the political obstacles that stand in our way to launching any program both internationally and domestically. The most important obstacle is the fossil fuel industry. Having said that, Hahnel strangely concluded that “fortunately, all this can still be done without replacing capitalism globally or in the United States, because that will take more time than we have to prevent climate change before it is too late.” But perhaps the latter will require the former?

Green energy ‘just transition’ and jobs

Robert Pollin of the University of Massachusetts-Amherst looked at the policies needed to support workers losing their jobs in energy transition. He reckoned that workers should be provided with three critical guarantees to accomplish this: no loss of jobs, compensation and pensions. Current transition policies do not provide such guarantees for assuring workers that they will not experience major living standard declines. And yet, the cost of ‘just transition’ is not high, according to Pollin, using a study of West Virginia’s fossil fuel industry dependent workers. It would amount to an annual average of about $42,000 per worker, or about 0.2 percent of West Virginia’s GDP. For the U.S. economy overall, a ‘just transition’ programme’s costs would total to about 0.015 percent of GDP.

There were also several presentations on debt and finance capital, all based on post-Keynesian financialisation models, which I don’t propose to discuss yet again in this post.

The contrast between the mainstream and the radical sessions

That’s it really all from the radical sessions: something on climate change; on financialisation; on imperialist exploitation; on planning; but nothing on AI – the key subject taken up by the mainstream. An interesting contrast: the mainstream looks for a saviour for capitalist slowdown; the heterodox and radical look at the contradictions within capitalist production.

From the blog of Michael Roberts. The original, with all charts and hyperlinks, can be found here.

The original blog includes links for downloading PDF versions of the papers referred to in the blog.