By Andy Ford

One of the best-known books in the English language is Strange Case of Doctor Jekyll and Mister Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson. But an interesting recent BBC programme presented by Scottish crime writer, Ian Rankin, draws out some of the roots of the story and its political aspects.

Stevenson was a sickly child, and spent a lot of time in bed. The family lived in Edinburgh, and employed a Fife country girl named Alison Cunningham to be his nanny. She entertained him with a mixture of fantastical Scottish folk tales and stories of Edinburgh’s dark past. One such story was of Colonel Thomas Weir, a devout puritan by day, but a sexual deviant by night. Weir and his sister lived a double life until they confessed and were executed in 1670.

The city of Edinburgh also had its own split personality. The ‘Old Town’ was deserted by the rising middle classes in Georgian times, and an elegant ‘New Town’ was built just next to it. The two were linked by bridges, so that servants could go to serve in the New Town by day, and the sons of the bourgeois, including the young Robert Louis Stevenson, could visit the drinking dens and brothels of the Old Town by night.

Edinburgh at that time was becoming a leading centre for medicine and surgery – but the doctors and students needed cadavers to work on. This had spawned a cottage industry of grave robbers or ‘Resurrection Men’ who went out at night with pick, shovel and sack to dig up the bodies of those newly-buried to sell to the anatomy schools and surgeons. A good team could raise a body in ten minutes, and maybe get half a dozen in a night. Each one could be sold for fifteen guineas, £1200 in today’s money. Stevenson’s story The Body Snatcher (1884) describes these macabre goings-on.

Imbalances in ‘bodily humours’

But Jekyll and Hyde is set in London, not Edinburgh. The reason is that the probable model for Dr Jekyll was the early surgical pioneer, John Hunter. Hunter rejected the then prevalent idea that disease was caused by an imbalance in the ‘bodily humours’ (blood, yellow bile, black bile and phlegm) and set out to work out how the human body really worked.

To do this, he needed bodies to dissect. He had his house specially constructed to facilitate his double life. He had bought a fashionable townhouse on Leicester Square for his practice as one of the leading doctors to London society, but he also bought the house behind in Castle Street (now Charing Cross Road) to house his dissecting room and anatomy school.

Grave robbers could come to the dingy door on Castle Street with their fresh acquisitions, to exchange the bodies for ready money. One medical student recalled, “There is a dead carcase at this moment bumbling up the stairs and the Resurrection Men swearing most terribly… I am informed that this will be the case most mornings at four o’clock”. The students actually had to live, sleep and work in the same room as the corpses they were working on.

The scruffy doorway in the book, from which we first see Mr Hyde emerging, is identical to the door at Number 13 Castle Street, at the rear of John Hunter’s elegant London mansion, and the floorplan of Jekylls’s house, as described in the book, is very close to John Hunter’s. The two faces of John Hunter – doctor to the King and the middle classes, but also the purchaser of stolen corpses, is clearly one of the key bases of Stevenson’s story.

Convulsions and vivid dreams

He got the idea for the transformation scene, where Dr Jekyll takes the serum he has developed and convulsively transforms into Mr Hyde, from a dream which he immediately recorded. Around that time, Stevenson was being treated with Ergotine (a derivative of a hallucinogenic fungus), for his TB haemorrhages. Ergotine causes convulsions and horribly vivid dreams, and clearly this is captured in the book, which might account for its huge and enduring popularity.

Stevenson actually wrote the book twice. According to his wife’s account, she read the first draft and told him that it was just a cheap horror story and that he could write a deeper and more significant book, whereupon he promptly burnt the manuscript.

But Ian Rankin, putting together multiple strands of evidence, argues that more likely the first draft was much more explicit about Mr Hyde’s crimes and depravities, including those of a sexual nature. Stevenson at that time was mainly known as a children’s writer, with Treasure Island, Kidnapped and A Child’s Garden of Verses selling well.

Fanny Stevenson, herself a published author, might have seen the story as a danger to his ‘reputation’ and sales. Unless, as his wife, she was troubled by material clearly rooted in Robert Louis Stevenson own nocturnal expeditions to the Edinburgh Old Town where, in his own words, “I used at one time have my headquarters in an old public house, frequented by the lowest order of prostitutes, thruppenny whores, where I used to go and write…they were really singularly decent creatures, not a bit worse than anybody else”.

In any event, Stevenson did burn his first manuscript, and in a mere five days wrote out a second, in which Hyde’s crimes, although pronounced to be ‘monstrous’, are specified in just two incidents – a vicious assault on a child, and the brutal murder of Sir Danvers Carew.

Paradoxically, it might be this lack of detail that allowed the first stage adaptations and early silent films to play up the dark nature of Mr Hyde’s deeds – and pull in the audiences. In one of the silent films, the star, John Barrymore, performed an extraordinary transformation scene with no special effects, and many of the other silent versions (available on YouTube) are genuinely chilling.

Homosexuality explicitly criminsalised

Jekyll and Hyde was published at the height of Victorian sexual hypocrisy, the year after the Labouchere Amendment of 1885, explicitly criminalised consensual homosexual acts between men in public or in private for the first time. There may be a homosexual theme in the book, as all Doctor Jekyll’s friends and companions are single, middle-class men, and when Stevenson was writing – in Bournemouth of all places – he was mixing with a group of gay men whose lives had just been criminalised and forced underground by Labouchere.

Stevenson’s book shines a light onto the hypocrisy of Victorian bourgeois morality and is still relevant today. Just look at Donald Trump and Elon Musk who have seventeen children between them by seven different women – all the while proclaiming “traditional family values” – or else the recent scandal over the wide use of prostitutes at the Davos summit of the ‘great and good’ of the capitalist world.

Not only does Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mister Hyde show the dual nature of human personality created by bourgeois morality and puritanism, but also the hypocrisy at the heart of capitalist society.

The BBC programme, Ian Rankin on Jekyll and Hyde is available to watch on BBC i-player here.

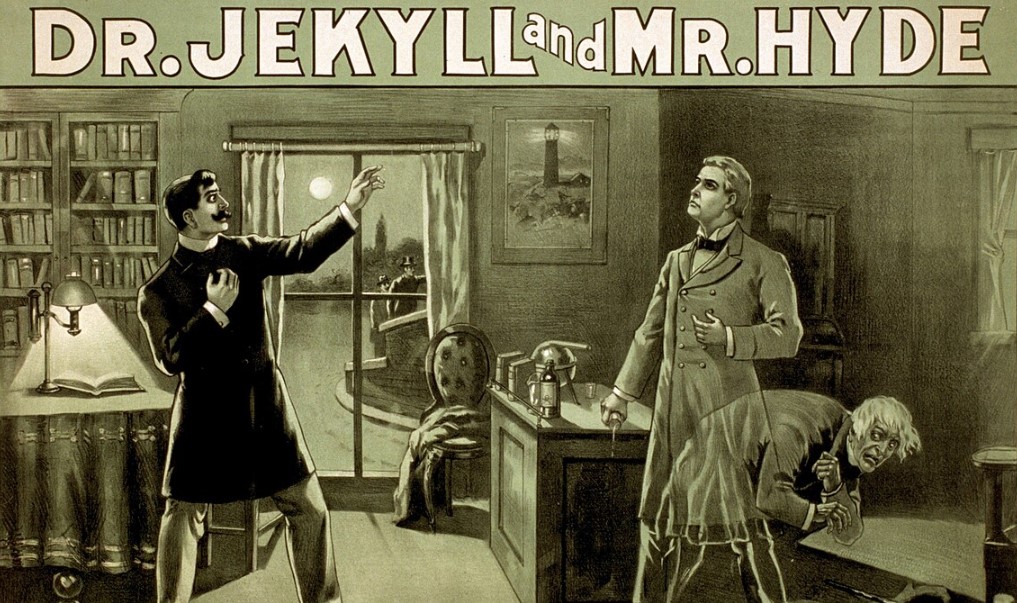

Feature picture shows an early poster of a play on Jekyll and Hyde, from Wikimedia Commons, here.