By Michael Roberts

Speaking to the US Congress yesterday after 100 days in office, President Donald Trump claimed that the new tariffs on imports from the US’s biggest trading partners would cause “a little disturbance”. But soon that would be over and “tariffs are about making America rich again and making America great again,” he said. “It’s happening, and it will happen rather quickly.”

Trump’s tariffs bring immediate retaliation

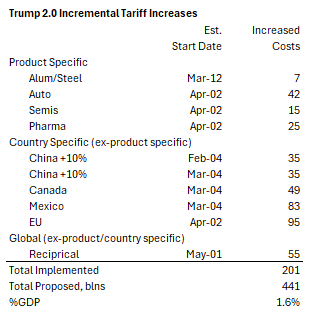

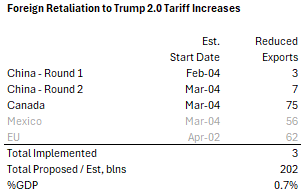

Indeed, very quickly. Yesterday, Trump imposed 25% tariffs on goods imported from Canada and Mexico into the US and an additional 10% tariff on Chinese imports, leaving all of America’s top three trade partners facing significantly higher barriers. The moves drew an immediate response from Beijing, which said it would levy a 10-15% tariff on US agricultural goods, ranging from soya beans and beef to corn and wheat from 10 March. Canada also unveiled tariffs on $107bn of US imports, starting with $21bn of imports immediately. “Canada will not let this unjustified decision go unanswered,” Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said. The levies against Ottawa are set at 25% except for Canadian oil and energy products, which face a 10% tariff. Canada accounts for about 60% of US crude imports.

China also targeted US companies, placing ten companies on a national security blacklist and slapping export controls on 15 others. It also banned US biotech company Illumina from exporting its gene-sequencing equipment to China. Beijing had added Illumina to its “unreliable entities” list last month in response to Trump’s initial barrage of tariffs.

Tariffs affect 42% of goods imported into the US

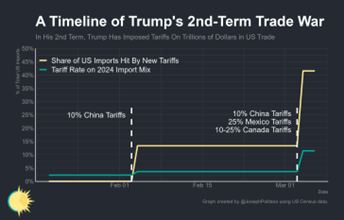

All the planned tariffs would take the US tariff rate to above 20% in just a few weeks, the highest since pre-WWI. As Joseph Politano points out, the costs of these actions are enormous, covering $1.3trn in US imports or roughly 42% of all goods brought into the United States, or the single-largest tariff hike since the infamous Smoot-Hawley Act of nearly a century ago.

Tariffs will raise costs of imported raw materials

The tariffs will drive up US prices for key raw materials like gasoline, fertilizers, steel, aluminum, wood, plastic, and more. Groceries, especially fresh fruits and vegetables from Mexico, will become harder to find. Manufacturing industries reliant on complex integrated North American supply chains—vehicles, computers, chemicals, airplanes, and more—could grind to a halt if those links are forcibly severed. Costs could spike for phones, laptops, and appliances where production is particularly concentrated in China and Mexico. Exporters will be hurt by increased costs for raw materials, currency appreciation, and upcoming retaliatory tariffs—all of which will cut into US economic activity.

The total costs of these tariffs would raise $160bn from US consumers and businesses paying more for their purchases of imported goods, with more to come. Trump’s Tuesday measures are only 40% of his proposed measures. If the next batch is implemented, it would raise the cost of imports to over $600bn, or 1.6% of GDP.

Is there an economic argument for imposing tariffs?

One economic argument for imposing tariffs on imported goods is to protect domestic firms from foreign competition. By taxing imports, domestic prices become relatively cheaper and citizens switch expenditure from foreign goods to domestic goods, thereby expanding the domestic industry. But this argument has little empirical support. The New York Fed recently analysed the impact of increased tariffs on domestic firms. It concluded that “extracting gains from imposing tariffs is difficult because global supply chains are complex and foreign countries retaliate. Using stock-market returns on trade war announcement days, our results show that firms experienced large losses in expected cash flows and real outcomes. These losses were broad-based, with firms exposed to China experiencing the largest losses.”

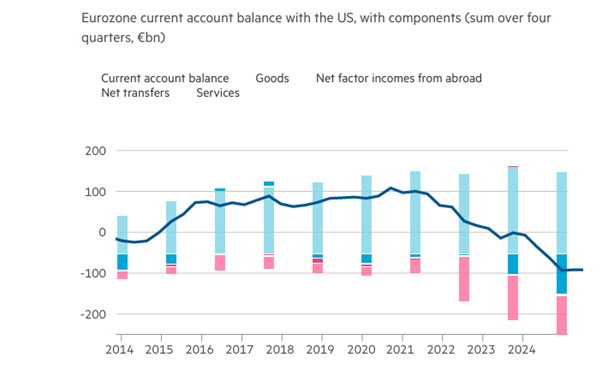

Moreover, as the Danish economist, Jesper Rangvid shows, Trump only looks at bilateral trade in goods, ignoring trade in services and earnings from capital and labour. It so happens that the income the US derives from its exports of services at least to the Eurozone and the returns on capital and the wages of labour it has exported there offset its bilateral deficits in goods. The overall Eurozone bilateral current account balance with the US is close to zero.

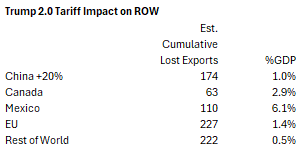

Likely economic outcome for the US and other countries

Far from Trump’s tariff barrage ‘making America great again’, it has every prospect of driving the US economy into a recession and the other major economies with it. The Kiel Institute reckons that EU exports to the US would drop by 15-17%, leading to “a significant” 0.4% contraction in the size of the EU economy, while US GDP would shrink by 0.17%. If there are tit-for-tat tariffs by the EU, that would double the economic damage and push inflation up by 1.5 percentage points. German manufacturing exports to the US would be the worst hit, dropping by almost 20%. While the exact magnitude of lost exports over time is unclear (given it will take time for supply chains to reset), if these levies persist it is likely to create a substantial drag on the GDPs of the major economies trading with the US.

The overall impact on US manufacturing could total nearly 1% of GDP in exports lost.

That’s one estimate. Yale University economists go further. They modelled the effect of the planned 25% Canada and Mexico tariffs and the 10% China tariffs, as well as the 10% China tariffs already in effect. They reckoned these tariffs would take the effective average tariff rate to its highest since 1943. Domestic prices would rise by over 1% pt from the current inflation rate, the equivalent of an average per household consumer loss of $1,600–2,000 in 2024$. They would lower US real GDP growth by 0.6% pt this year and take 0.3-0.4% pt off future annual growth rates, wiping out expected gains in productivity from AI infusion.

So worried is the International Chamber of Commerce in the US, that it reckoned that the world economy could face a crash similar to the Great Depression of the 1930s unless Trump rows back on his plans. “Our deep concern is that this could be the start of a downward spiral that puts us in 1930s trade-war territory,” said Andrew Wilson, deputy secretary-general of the ICC. So Trump’s measures may go well beyond “a little disturbance”.

The current state of the US economy

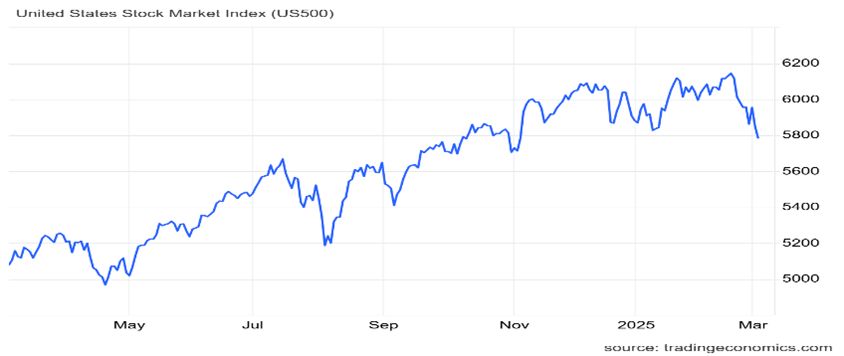

Even before the announcement of the new tariffs, there were significant signs that the US economy was slowing at some pace. The impact of increased import tariffs could be a tipping point for a recession. Wall Street thought so. When Trump announced the tariff measures, all the gains in the US stock market made since Trump’s election victory were wiped out.

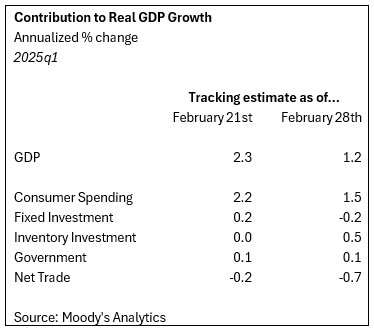

In a matter of weeks, the narrative over the US economy has shifted from the “exceptionalism” of the US economy to alarm about a sudden downturn in growth. Retail sales, manufacturing production, real consumer spending, home sales and consumer confidence indicators, are all down in the past month or two. Consensus forecasts for real GDP growth for Q1 2025 are now only an annualised 1.2%.

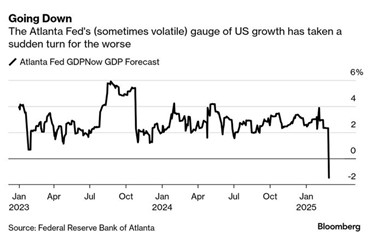

The closely followed Atlanta Fed’s GDP NOW tracker forecasts an outright contraction.

US manufacturing has been in recession for a year or more, but what is also worrying in the latest indicators of manufacturing activity was a significant rise in costs: “demand eased, production stabilized, and destaffing continued as companies experience the first operational shock of the new administration’s tariff policy. Prices growth accelerated due to tariffs, causing new order placement backlogs, supplier delivery stoppages and manufacturing inventory impacts”, Timothy Fiore, Chair of the ISM said. New orders fell the most since March 2022 into contraction territory and production slowed sharply. In addition, price pressures accelerated to the highest since June 2022.

The stark economic reality facing US households

But then the so-called exceptionalism of the US economy since the end of the pandemic was always a statistical illusion. One study reveals the real story for many American households on employment, wages and inflation.

First, there is the near-record low unemployment on official figures, just 4.2%. But this figure includes as employed, homeless people doing occasional work. If the unemployed included those who can’t find anything but part-time work or who make a poverty wage (roughly $25,000), the percentage is actually 23.7%. In other words, nearly one of every four workers is functionally unemployed in America today. The official median wage is $61,900. But if you track everyone in the workforce — that is, if you include part-time workers and unemployed job seekers, the median wage is actually little more than $52,300 per year. “American workers on the median are making 16% less than the prevailing statistics would indicate.” In 2023, the official inflation rate was 4.1%. But the true cost of living rose more than twice as much — a full 9.4%. That means purchasing power fell at the median by 4.3% in 2023.

European countries plan to spend more on the military

The European leaders’ answer to Trump’s tariff moves and his apparent withdrawal from supporting Ukraine in its war against Russia now appears to be preparations for more war. Global defence spending hit a record $2.2tn last year and in Europe it rose to $388bn, levels not seen since the ‘cold war,’ according to the International Institute for Strategic Studies. Martin Wolf, the liberal Keynesian economic guru of the Financial Times says “spending on defence will need to rise substantially. Note that it was 5 per cent of UK GDP, or more, in the 1970s and 1980s. It may not need to be at those levels in the long term: modern Russia is not the Soviet Union. Yet it may need to be as high as that during the build-up, especially if the US does withdraw.”

How to pay for this? “If defence spending is to be permanently higher, taxes must rise, unless the government can find sufficient spending cuts, which is doubtful.” But don’t worry, spending on tanks, troops and missiles is actually beneficial to an economy, says Wolf. “The UK can also realistically expect economic returns on its defence investments. Historically, wars have been the mother of innovation.” He then cites the wonderful examples of the gains that Israel and Ukraine have made from war: “Israel’s “start up economy” began in its army. The Ukrainians now have revolutionised drone warfare.” He does not mention the human cost involved in getting innovation by war. Wolf: “The crucial point, however, is that the need to spend significantly more on defence should be viewed as more than just a necessity and also more than just a cost, though both are true. If done in the right way, it is also an economic opportunity.” So war is the way out of economic stagnation.

Germany’s Chancellor-to-be Friedrich Merz (after winning the recent election) has adopted the same story. In a complete about-face from his election campaign, when he opposed any extra fiscal spending in order to ‘balance’ the government books, he is now promoting a plan to inject hundreds of billions in extra funding into Germany’s military and infrastructure, designed to revive and re-arm Europe’s largest economy. A new provision would exempt defence spending above 1 per cent of GDP from the “debt brake” that caps government borrowing, allowing Germany to raise an unlimited amount of debt to fund its armed forces and to provide military assistance to Ukraine. And he plans to introduce a constitutional amendment to set up a €500bn fund for infrastructure, which would run over ten years. Suddenly, there is plenty of cash and borrowing to be made available for arms and military ventures.

Impact of cutting aid to countries in the global south

The UK’s plan is to double its ‘defence’ spending by cutting its aid programme to the poor countries of the world. Trump also has frozen US foreign aid. Global debt has hit $318trn with a rise of $7trn in 2024. Global debt to global GDP rose for the first time in four years – so debt rose faster than nominal GDP to reach 328% of GDP. The Institute of International Finance (IIF) warned that poor countries are under immense pressure as their debt loads continue to grow. Total debt in these economies jumped by $4.5 trillion in 2024, pushing total emerging market debt to an all-time high of 245% of GDP. Many of these poor economies now have to roll over a record $8.2 trillion in debt this year, with about 10% of it denominated in foreign currencies—a situation that could quickly turn dangerous if funding dries up. So more war and more poverty ahead.

From the blog of Michael Roberts. The original, with all charts and hyperlinks, can be found here.