By Maureen Wade.

(Chair, Birmingham UNISON retired members’ section)

This year, International Women’s Day coincides with the 170th anniversary of the birth of Eleanor Marx, the international socialist, feminist, and trade unionist. She has always been overshadowed by her father, Karl Marx, but she played a pivotal role in the formation of the trade union movement and the foundation stones of socialist politics in the UK. As her biographer Rachel Holmes put it: “If Marx and Engels were the theory, Eleanor was the practice.”

Born in London in January 1855, in Victorian Britain she had no right to education, was barred from university, from voting or standing for parliament, and from most professions. Despite the obstacles, she demonstrated a towering intellect. Known within her family as ‘Tussy’, she spent much of her early adult life editing her father’s world-changing thesis, Das Kapital, and many other of Karl Marx’s major works, and translated Flaubert’s Madame Bovary into English for the first time.

But she was no desk-bound academic; she was primarily a socialist activist and trade unionist. Following her father’s death, she retained the close family relationship with her father’s long-time political ally, Frederick Engels. She often said she had ‘two fathers’, Marx and Engels.

The misogyny of Victorian capitalism

In 1884, she met the feminist trade unionist, Clementina Black, and became involved in the Women’s Trade Union League. For these socialist feminists, women’s liberation was linked with iron chains to the class struggle. Particularly in their trade union work, to cut through the enforced misogyny of Victorian capitalism in the fight for equal pay, Eleanor and the WTUL had a simple message to male workers – as long as women were paid less than men, they would always be a cheap ‘reserve army of labour’ ready to be exploited by the bosses, to undercut the pay and conditions of male workers. The message hit home.

Eleanor would go on to actively support numerous strikes, including the Bryant & May ‘Match Girls’ strike of 1888 and the London Dock Strike of 1889. At a time when socialists were banned by law from addressing crowds, she was a popular street orator being nicknamed affectionately by London workers as ‘Our Old Stoker’ and ‘Our Mother’.

Eleanor threw herself into the tide of ‘New Unionism’. Until the 1880s, trade unionism had been limited to skilled workers in craft-based unions, but the new movement saw whole industries being unionised, whether skilled or unskilled workers, often in ‘industrial unions’.

Eleanor had met a young, semi-literate worker from Birmingham called Will Thorne, whose early life was typical of the appalling conditions faced by the working class. Thorne began his working life at the age of six, as a wheel turner for rope and twine spinners. Despite all the activism, as Eleanor did with many new working class recruits to the cause, she helped Thorne improve his reading and writing skills. He went on to become the General Secretary of the TUC.

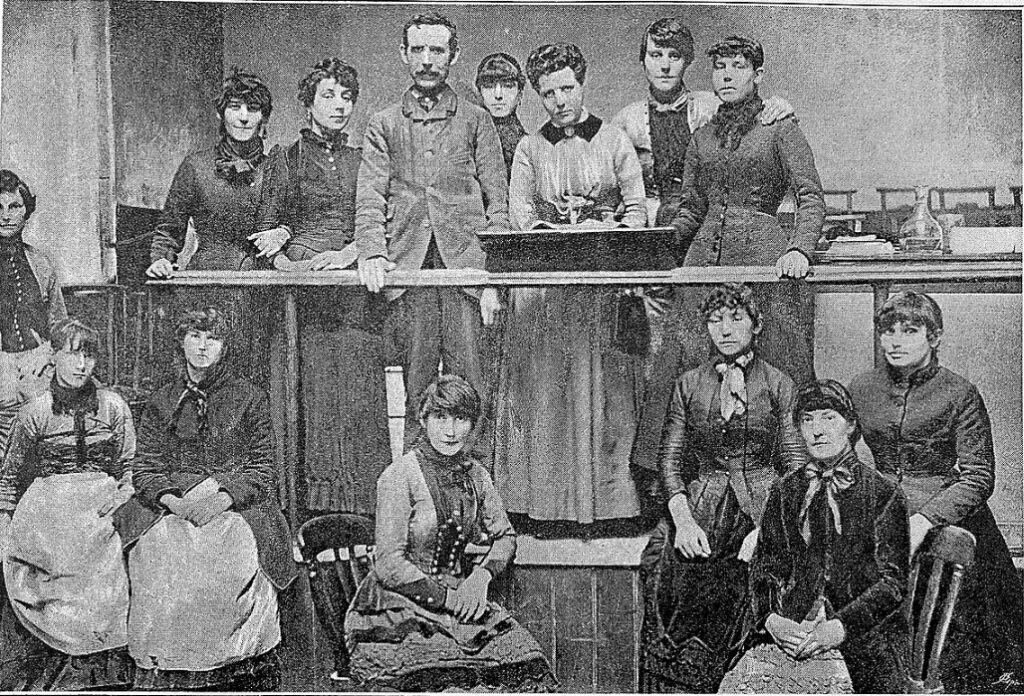

In 1889,Eleanor and Thorne together launched the National Union of Gas Workers and General Labourers, wanting to reduce the working day from 12 to 8 hours, to establish double rates for Sunday overtime, as well as involving women in every aspect of union membership and leadership. It was the first union ever to establish women’s branches. Within six months, union membership had swollen to over 20,000. This union was the forerunner of today’s GMB union.

Social Democratic Federation

Eleanor was no syndicalist however, and understood that the industrial struggle for workers’ rights had to be intrinsically linked to the political struggle for socialism. She was an early member of the Social Democratic Federation, but like many on the left, had despaired of the autocratic rule and unquestioning nationalist patriotism of its leader, Henry Hyndman. He naively thought that his approach would gain sympathy for workers from the ruling class and his supporters were dubbed the ‘Jingo Faction’. So in 1884 Eleanor was with many others on the left who split from the SDF to form the Socialist League.

Unfortunately, the Socialist League soon became a battleground between the socialists and anarchists. Eleanor felt that the ‘revolutionary purism’ of the likes of William Morris was just a cover for inaction. Her rift with the ‘talking shop’ anarchists – and the ‘intellectual left’ generally – concretised at the ‘Bloody Sunday’ events.

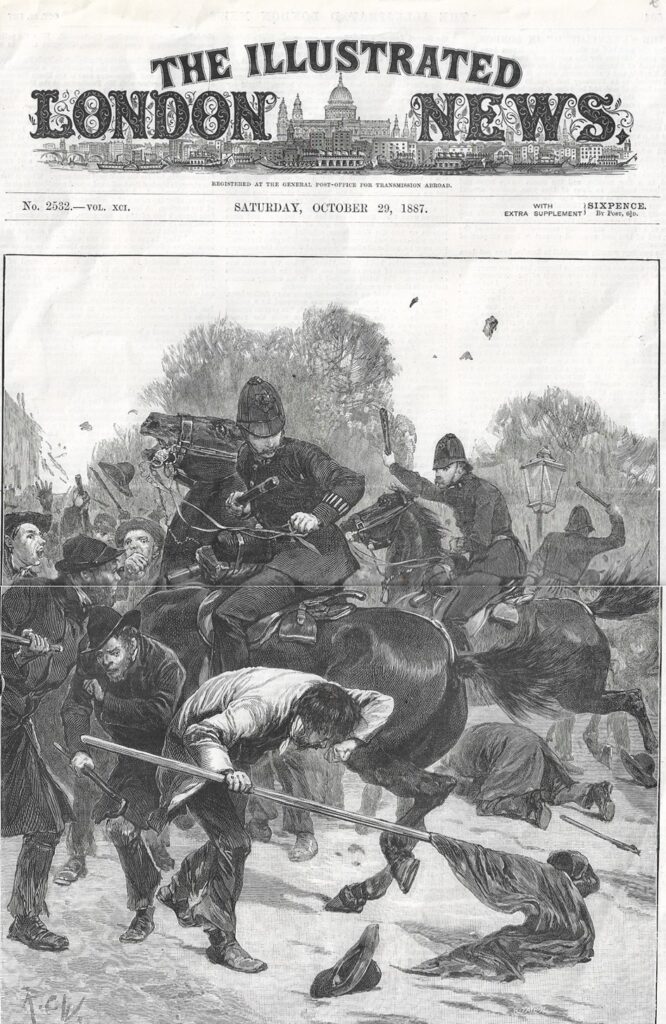

Bloody Sunday, 1887

Eleanor took an active role in organising the London trade union demonstration of 13 November 1887, leading to what became infamously known as the first ‘Bloody Sunday’.

There had been regular protests by the trade unions and the unemployed in central London, and a new protest was planned for Trafalgar Square on November 13. This time, the capitalist state cracked down and the march was banned (nothing changes!).

But the mass of workers gathered anyway in Charing Cross and began to move towards Trafalgar Square. Their way was barred by 4,000 police, 300 Grenadier Guards, each armed with 20 rounds, and 250 Household Cavalry. The Police and Army unleashed an unprovoked attack on the protesters, injuring over 200 workers, three of whom later died from their wounds.

As the police attacked the march, the socialist intellectuals like George Bernard Shaw and the anarchists around William Morris all fled the scene at the first sign of trouble. As Eleanor Marx later contemptuously commented: “… our fire-eating anarchists here as usual are getting frightened now there really is a little danger” (Letter, 16 November, 1887).

Eleanor by contrast, stood firm, despite being twice assaulted by police. She had been a staunch supporter of Irish Republicanism, and Irish workers rallied around her. She led them through the back streets of Victoria to continue the protest at Westminster, only to be battered again by a new police charge.

When worried friends later asked the family if Eleanor had survived the ordeal, Engels jokingly replied: “Tussy wasn’t attacked. It was Tussy doing the attacking!” (Eleanor Marx – A Life, by Rachel Holmes).

After the Socialist League was finally taken over by the anarchists, Eleanor rejoined the SDF, but by 1895 this too was beginning to factionalise, either between the syndicalist wing who saw the road to socialism through New Unionism, or the bitter disputes between socialists on whether to stand in Parliamentary elections. Engels agreed with Eleanor that: “… whilst the socialist instinct grew stronger amongst the masses in England, as soon as it came to translating this into clear demands and action, everyone fell apart” (Eleanor Marx – A Life, by Rachel Holmes).

The need to build mass support for socialism

Eleanor, the ‘Old Stoker’, understood the need for propagandist work at this stage to build mass support for socialism and internationalism. She argued in the SDF that it was not a question of some ‘unbreakable principles’, but one of tactics, and that international socialists should exploit whatever avenue gave them a platform before the masses, whether outside the factory gate, on picket lines or even in a parliamentary election, although on the latter she warned there should be no illusions that ‘bourgeois democracy’ would ever allow the triumph of socialism.

Eleanor’s last major contribution to international socialism was on the Second International, where revisionists, led by the German Social Democrats and the so-called Austro-Marxists were taking hold.

As a cover to their drift towards ‘gradualism’ and developing illusions in capitalist democracy, they argued that Karl Marx’s analysis of capitalism was now ‘out of date’. They became increasingly infuriated with Eleanor Marx, who, of course, had an encyclopaedic knowledge of her father’s works.

She could challenge them when they tried to dress up or mangle a Marxist theory to justify their new reformism, or pointedly asking them to explain just how exactly had capitalism fundamentally changed over the past three decades? Above all, she patiently explained her father’s premise that capitalism would never reform itself out of existence.

Eleanor had confidence in the working class and a clear perspective that revolutionary upheavals and opportunities were rapidly approaching. As such, she lambasted the Social Democrats for their timidity, writing: “… capitalist society is digging its own grave so rapidly I am afraid it will tumble into it before the Social Democrats are ready” (Justice, journal of the SDF, 9 June 1897).

Zimmerwald Socialists around Lenin

Unfortunately, she could not win them back to international socialism, and the path was set for the tragedy of 1914, when, with the exception of Lenin and the ‘Zimmerwald Conference’ socialists, the leaders of the Second International all obediently filed behind their respective imperialist powers for the slaughter of the First World War.

Sadly, Eleanor’s personal life was less successful than her political one. At the age of 16, Karl Marx made her his secretary, travelling together to international socialist conferences around Europe. She fell in love with Prosper-Olivier Lissagaray, a journalist and participant in the Paris Commune, who had fled to London after the suppression of the Commune. Karl Marx was still first and foremost a father, and he disapproved of the relationship because of the age gap between the two, Lissagaray being 34 years old.

Sure enough, this troubled relationship soon broke down, and she then spent the rest of her short life with a fellow SDF member, Edward Aveling. Aveling’s behaviour was appalling and he was repeatedly unfaithful. There were allegations of him stealing money from the movement, not to mention Eleanor’s money that was provided for her by Engels, as well as general mental cruelty towards her.

Tragically, at the age of only 43, in March 1898, Eleanor poisoned herself after discovering that Aveling had secretly got married the previous year. Her ashes were eventually laid alongside her father in Highgate Cemetery.

It is a tragedy she did not survive – there is no question that had she done so, in the tumultuous events of the early twentieth century, we would be talking of her in the same breath as Rosa Luxembourg, Clara Zetkin and Sylvia Pankhurst.

In remembering Eleanor Marx, we should never forget that many of the freedoms and benefits we enjoy today (and sadly need to keep defending) are a direct result of the foundation stones laid by Eleanor Marx and the women and men like her – the eight-hour day, the outlawing of child labour, access to equal education, trade unionism and universal suffrage. She was a true socialist feminist.

[Rachel Holmes’ book, Eleanor Marx – a Life, is still available. It is published by Bloomsbury]

It is not certain that she poisoned HERSELF. Aveling was a monster and the death was suspicious.