By Michael Roberts

Pausing on further analysis on Trump, trade and tariffs, this post is on economic history.

Robert Dees has written an opus of over 1700pp in two huge volumes, called The Power of Peasants – the economics and politics of farming in medieval Germany. Dees argues that, contrary to mainstream economic history, peasants or farmers in overwhelmingly agricultural ancient and medieval economies played an essential role in advancing civilisation in Europe.

Civilisation in this context means raising the productivity of labour through improvements in farming technique and technical innovations—the farmers’ “creative genius”—and thus the living standards and the health of the multitude. The peasants were not some amorphous dull mass that were just victims of class rule by Roman slaveholders or feudal lords. They had agency; they fought on many occasions (not often successfully) to break the grip of the ruling class. When they succeeded and gained a degree of independence in production and control of the surplus produced, they took society forward.

The economic impact of suppressing peasants in history

When the peasants were suppressed and the ruling class replaced them with slaves as in the Roman empire; then the Roman empire went into economic crisis and eventually collapsed. When the peasants were subjected to the penuries of serfdom under the rule of petty feudal regimes, eventually the feudal order fell into a series of plague-ridden crises and perpetual wars that sucked out any progress.

The main focus of Dees’ book is on the economics and politics of farming in south Germany from 1450 to 1650. But he starts with the role of farmers/peasants in building the Roman republic and driving its successful expansion. It was when the ruling orders replaced free farmers with slaves from conquests in war, driving the peasant citizens into debt and expropriating their land for huge estates, that Roman society went into crises that led to class battles, civil wars, the end of the republic and then eventually to internal collapse and external invasion by the peasant ‘barbarians’ from the north. These peasant ‘barbarians’ from northern Europe had developed farming that produced “more food, more farmers, more warriors, until they overran the empire.”

The Roman slave economy did collapse

Dees disputes the common mainstream revision that Rome did not collapse, but instead morphed into ‘late antiquity’ and then slowly evolved into a feudal system. In his view, and I agree, the Roman slave economy did collapse and productivity, technology and culture dropped away. As he says, in 900, more than four hundred years after the end of the Western Roman empire, “there was not a single city in England and few in northern Europe”.

But it was about then that a revival in productivity and innovation resumed, powered by peasant farmers now freed from Roman slavery. Although a new feudal class formed, in the early medieval period, it was still too weak and disparate to suppress the peasantry. But gradually the feudal lords exerted more control. As a result, agriculture began to stagnate and Europe descended into internal warfare and the feudal lords launched their ‘crusades’ against the muslims in Palestine (and pogroms at home against the jews) to cement their control. As poverty rose and health and nutrition fell, disease became the norm (Black Death etc) and feudal rulers engaged in what became the Hundred Years War of the 14th and 15th centuries. Although peasant revolts erupted, they were crushed.

The weakening of the feudal class in England

But the plagues and the continual wars, in particular, the War of the Roses in England in the mid-15th century, so weakened the feudal class that the peasantry regained some independence over their production. Eventually, in combination with the artisans, shopkeepers and merchants of the towns, they were able to escape from feudal penury. The republics of the Netherlands and England emerged and opened the door for a new mode of production based on capitalism, made possible by the revival of the productive use of the agricultural surplus.

Within his two volume opus, Dees inserts his more detailed analysis of the history of England from pre-historic times that he previously published separately. This is a highly entertaining robust account of invasions, wars, class rule and rebellions that is worth a read on its own account.

Agricultural and commercial progress was possible in England and the Netherlands. In Germany, where Dees concentrates his analysis, that did not happen. The petty feudal regimes triumphed over the peasants in a series of class wars (eg the peasant war of 1524-25). As a result, rents and debt spiralled and farmers could do nothing to raise productivity. Germany stagnated in a feudal quagmire. The thirty years war of 1616-48 was the culmination of feudal stagnation and collapse.

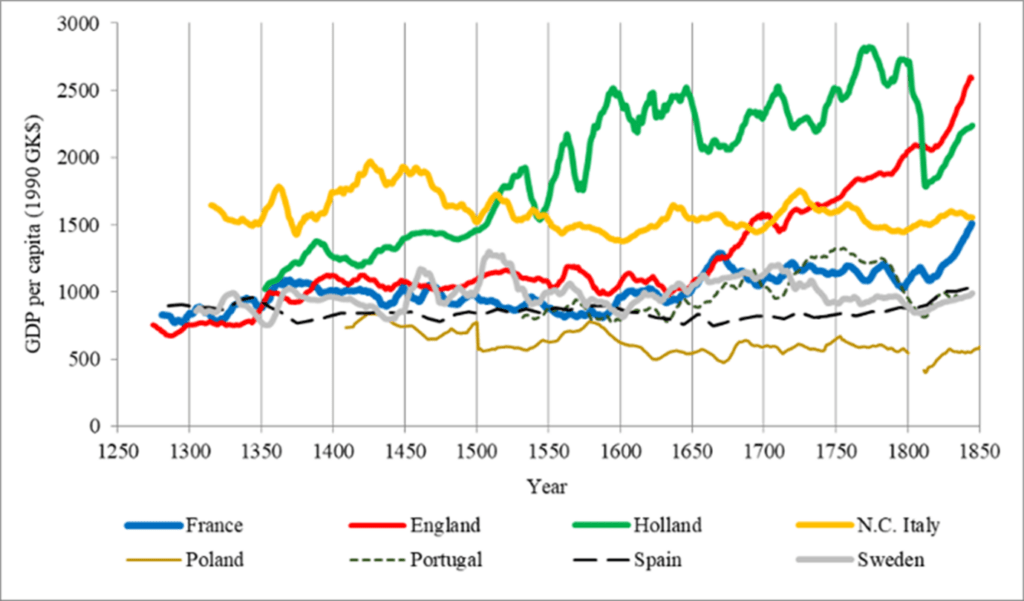

GDP per capita trends across medieval Europe

You can see the difference in GDP per capita in the figure below. The Renaissance Italian city states were the leaders in per capita GDP in Europe up to the mid-15th century (yellow line) and then the Netherlands began to catch up and lead from the 1550s (green line). England started to close the gap after the civil war of the 1640s destroyed feudalism and eventually overtook Holland through industrialisation in the late 18th century onwards (red line). In the meantime, continental Europe stagnated, with France only taking off after the late 18th century revolution freed the peasants from feudalism (blue line).

On France, Marx put it in the 18th Brumaire: “After the first Revolution had transformed the semi-feudal peasants into freeholders, Napoleon confirmed and regulated the conditions in which they could exploit undisturbed the soil of France which they had only just acquired, and could slake their youthful passion for property ….Under Napoleon the fragmentation of the land in the countryside supplemented free competition and the beginning of big industry in the towns. The peasant class was the ubiquitous protest against the recently overthrown landed aristocracy. The roots that small-holding property struck in French soil deprived feudalism of all nourishment. The landmarks of this property formed the natural fortification of the bourgeoisie against any surprise attack by its old overlords.”

Demolishing the population theory of Thomas Malthus

Dees does a demolition job on the population theory of the reactionary 19th century English parson, Thomas Malthus, who argued that stagnation in production was the product of overpopulation. Europe could not support ‘too many people’. This ‘dogma’ has been refuted by many since. Dees cites Walter Blith, yeoman farmer and captain in the Cromwell’s parliamentary army during the English civil war that “any land by cost and charge may be made rich and rich as land can be”. Dees also cites Engels (which I also did in my book Engels 200) on refuting Malthus: “the productive power at humanity’s disposal is immeasurable. The productivity of the soil can be increased infinitely by the application of capital, labour and science.” As Dees says, “the Netherlands has a population density more than eleven times that of the Congo. According to the ‘Malthus fraud’, the people of the Netherlands must be starving and those of the Congo prospering.” Engels remarked that if Malthus wanted to be consistent, he must “admit that the earth was already overpopulated when only one man existed.”

And yet the Malthusian argument continues to find its way into mainstream economics to this day, even though the main theme now is that the world produces too much and people consume too much and so are destroying nature and the planet. Dees argues that it was feudalism and class rule that made people poor and starving and suffering from plagues, not because there were too many people. Now the argument should be that nature and the planet is being destroyed by capitalism and rule of the rich oligarchs, not because of too much production.

Summarising the contribution of the peasantry in European history

Dees offers the reader a materialist conception of history in his account of the role of the peasantry in Europe since ancient Rome. Rome’s rise was powered by free farmers; its decline and collapse was caused by suppression of those farmers by a slaveholding aristocracy and emperors. Northern Europe freed itself from Roman rule and peasant farming was able to expand production and feed more people. However, a feudal aristocracy based on armed might was eventually able to subject most of the peasants into serfdom and to live off their labour, thus ending agricultural progress. Only when feudalism collapsed through wars and plagues did Northern Europe’s revolutions allow the peasantry to revive innovative farming.

In Germany, feudalism was sustained, thus delaying there the emergence of capitalist agriculture and commerce well into the 19th century. Dees provides a new explanation for the causes of the Peasant War of 1525 and the long-term effects of its defeat—both contrary to existing scholarship. This will be of particular interest in this 500th anniversary year of that event.

From the blog of Michael Roberts. The original, with all charts and hyperlinks, can be found here.