By Beatrice Windsor

Last year was the eightieth anniversary of the threat of Nazi invasion. Commentators at the time said that there was a ‘big three’ who maintained public morale with regular national radio broadcasts: Churchill, JB Priestly and Tom Wintringham. During the anniversary we heard much about Churchill and to an extent JB Priestly. But there was a wall of silence about Wintringham.

Wintringham has been airbrushed out of British history, despite being a major influence on many key events of the twentieth century. A review of Hugh Purcell’s autobiography of Wintringham is therefore timely. The Last English Revolutionary is one of the very few books to be written on the subject. It is worth reading just for the picture it paints of the early days of the British Communist Party, and its poisonous Stalinist degeneration.

All set to go up to Oxford

Wintringham was born into a bourgeois Liberal family, which effectively ran Grimsby, with his father and uncles holding nearly all seats of influence on the town’s council and boards. Wintringham looked set to follow this tradition and was due to go to Oxford University to study Law, but World War intervened, and in 1916 he volunteered for active service. True to his early egalitarian liberal values, he refused to become an officer and joined as a private.

His two years on the grim Western Front turned him from being a mild liberal socialist into a hard-bitten Bolshevik. After the War, he took up his place at Oxford and immediately fell in with the early British Communist group there, including Rose Cohen and Andrew Rothstein, whose father was the Bolsheviks’ main organiser in London.

The Bolshevik leader, Kamenev, attended the founding meeting of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) in 1920. Impressed by his contributions, Kamenev gave Wintringham a letter of introduction after he outlined his plan to travel to Moscow. Despite the dangers – Britain still deemed revolutionary Russia “an enemy power” – Wintringham made it there in the same year.

Translating Russian broadcasts

In Russian, he was given work translating Soviet radio broadcasts into French and English. He also befriended John Reed, the US journalist who authored 10 Days That Shook the World and nursed him as he died from typhus. Like many early British communists, Wintringham was most impressed by Trotsky, and attended a rally at the Moscow Opera House:

“We stood on tiptoes at the back of the Tsar’s Box. The enormous place was packed. The stir through the audience when Trotsky got up was extraordinary. He spoke very simply: there was no striving for effect.”

On return, he became a leading member of the early CPGB, editing the party’s journal, Labour Monthly, for its members in the Labour Party, and he then became assistant editor of Workers’ Weekly, the forerunner of the Daily Worker.

The CP had been enthusiastically pursuing Lenin’s line on working to gain influence in the new Labour Party and were oblivious to the intense battles going on in the Soviet Union, as the Stalinist bureaucracy began to take hold and isolate the early Bolshevik leaders around the Left and Right Opposition groups, and Trotsky in particular.

The Comintern lurches left

They were therefore stunned when they received a letter, in May 1924, from Zinoviev, then head of the Comintern (Communist International, announcing the beginning of a sharp policy turn, whereby the mass social democratic workers’ parties like the Labour Party, were to be denounced. This threw the CPGB into confusion, with their main theoretician, Palme Dutt, responding:

“The workers’ awakening to the struggle for power was finding expression within the Labour Party, despite Labour’s bourgeois policy and leadership. The Labour Government is ‘their government’ and the workers are strongly hostile to any attacks on it, not on the grounds of disagreement with the issues, but because they feel their class solidarity is being attacked.”

This was to be the last time any of the CPGB criticised the Stalinist regime, and from then on the Party would slavishly follow the ‘party line’ dictated to them from Moscow. This intensified after the failure of the 1926 General Strike.

CP membership doubles, then collapses

In the demoralising atmosphere of defeat, the shrill ultra-leftism of Stalin’s “class against class” policy did win over many young workers frustrated at the defeat and the CPGB’s membership doubled. Sales of Workers’ Weekly hit 80,000, with Wintringham’s editorials proving popular.

But this gave rise to a false perspective, that ‘revolution’ was just around the corner, when in fact the mass labour movement was in retreat. As a miner delegate to the CPGB’s Party Congress in 1930 caustically remarked: “Comrades speak of the radicalisation of the masses and the great wave of insurrection… I have not seen a ripple of it.”

Sure enough, by 1931 the CP membership collapsed to 3,500. This led to bitter recriminations within the CP where the frustration could only be eased with ritual purges – Wintringham went along with this, even supporting the expulsion of his old comrade Andrew Rothstein.

Venom directed at ILP leaders

A further opportunity was squandered in 1932, when the Independent Labour Party, led by Fenner Brockway, split from the Labour Party not long after the Labour leader Ramsay McDonald had formed a National Government. There was some hope that a merger between the leftward moving ILP and the CPGB would form a new force on the left of the labour movement. But the ultra-left sectarianism of the CPGB ensured this did not happen. A typical example of their venom is a note, written by Palme Dutt to the CP general secretary Harry Pollitt, before a public debate he was to have with Brockway:

“No politeness! No more ‘difference of opinion’. No parliamentary debate. No handshakes. Treatment is CLASS ENEMIES throughout. You speak of the holy anger of whole international working class against the foulness that is Brockway. Make the whole audience HATE him.”

Wintringham rebelled against this sectarian cul-de-sac and, demonstrating his independent thinking, in 1935 he penned support for the new policy being pursued in France – the Popular Front. In an article under the slogan ‘Allies are needed for the Revolution’, he railed at the isolation of the CP as the fascist threat grew all across Europe. Betraying his Liberal roots, he argued for unity with liberal and progressive capitalists and religious movements against tyranny.

Revolution breaks out in Spain

This caused outrage within the CP, which denounced him in their publications and refused to print his replies in the Daily Worker. Still ‘reduced’ in the ranks of the CP, with the outbreak of the Civil War in Spain, he put his popular front model into action to raise funds for ambulances for the Republicans through the Spanish Medical Aid Committee (supported by the ‘social fascist’ Labour Party, ILP, the trade unions and various liberal and Christian organisations) and he arrived in Spain with the first delivery.

But unlike the British CP, Wintringham was now in step with Stalin. Moscow was zig-zagging again. After the bitter lessons of their ultra-left turn in the early 1930s, they lurched towards the Popular Front model, hoping to produce ‘progressive’ – yet still capitalist – governments in Europe that would align with the isolated Soviet Union. Stalin wagered that the open class warfare of the past few years would be a barrier to this, and might encourage Western Europe to turn a blind eye to Hitler invading the Soviet Union, which, given that Stalin had purged the best elements from the Red Army, was now effectively defenceless.

Formation of the International Brigade

In Spain, Wintringham encountered German socialists who had fled the Nazi regime to fight fascism. This inspired him for a new idea – an ‘International Brigade’, made up of socialist and communist workers from across the world to fight alongside the Spanish Republic against the fascist threat, a call already being made by the French Communists.

He put this idea to the British CP. His anger grew as they dragged their feet for three months – they would not take any decision until they got the nod from the Comintern; they pathetically explained the delay was because Moscow was too tied up with the (show) trial of Zinoviev. Eventually Moscow agreed, and nearly 50,000 workers volunteered from around the world, including over 2,000 from Britain.

As leader of the British section, the XV Brigade, Wintringham won fame in the British labour movement after the Battle of Jarama in 1937. Madrid was in danger of being encircled by the far superior fascist forces but were held off – albeit temporarily – by his brigade. Numbering only 400, they suffered two thirds killed, wounded or taken prisoner, yet still held the line, Wintringham himself being wounded.

Slavish loyalty to the CP

Receiving hero status after Jarama, Wintringham backed Stalin and the Popular Front model all the way, giving enthusiastic support for the new party line of ‘Everything and everybody for the winning of the war’. He supported the subsequent purging and executions of the Trotskyists and anarchists of the POUM, denouncing them as the “uncontrollables”.

Despite his slavish loyalty, Wintringham naively underestimated the level of paranoia that now gripped Moscow and its adherents, who saw ‘Trotskyite wreckers’ around every corner. Wintringham’s downfall was to leave his wife in England and take up with Kitty Bowler, an American journalist covering the Civil War. She was later arrested and accused of being a ‘Trotskyite spy’, and expelled from Spain.

Wintringham, wounded for a second time, re-joined Bowler in London, only to be told by the British CP that he must leave Bowler or face expulsion. By 1938, the British CP was gripped by the same Stalinist terror that was smothering Communist Parties around the world. Purcell comments:

“The answer lies in the reign of terror in Russia. Senior members of the (British) Party were petrified they might lose their jobs or even their lives if they showed the slightest taint of Trotskyism. At the very time that Tom was fighting for his professional life, his old friend Rose Cohen was waiting to be shot in Moscow. Her husband, Max Petrovsky, had been arrested the previous year as a wrecker – he had known Trotsky – and all British Communists who knew him had to make statements.”

Workers demanded serious fight against Nazis

Wintringham was out in the political wilderness, but now free of the party line. He launched a series of populist campaigns that, given his standing as the ‘hero of Jarama’, the labour movement listened to. They wanted to prepare for war with Nazi Germany with or without the British ruling class, which was riddled with appeasers and defeatists, or as in the case of the elite set around the Duke of Windsor, openly supported Hitler.

Wintringham’s first campaign in 1938, under the slogan ‘Dig or Die’, was to form the ‘Barnsbury Diggers’ in north London. Recruiting ex-servicemen and the unemployed, without permission they dug trenches in local parks and open ground as crude preparations against air attack. The popular support this received forced the authorities to act, and within days the Chamberlain government announced the formation of the Air Raid Precautions (ARP) service, and crude air raid shelters were dug in parks across London.

Wintringham began to build a mass base of support for his war preparations, being employed by both the Daily Mirror and the Picture Post to provide regular columns for their seven million readers. Supported by George Orwell, his main message was one of ‘revolutionary patriotism’ – the Nazis could only be beaten by an armed people, and one fighting not just against fascism, but for socialism: that had been the key to the mobilisation of the Spanish people.

Many in British establishment favoured appeasement

Beside his newspaper columns, his books and pamphlets sold in their thousands. He didn’t just win mass support in the labour movement. Those in the highest sections of the British establishment who opposed appeasement accepted his ideas. He was regularly invited to the War Office to meet senior major generals – at one point even the Deputy Chief of the Imperial Staff – to discuss the guerrilla tactics he employed in Spain.

As Wintringham’s campaign for a “a properly armed irregular army ready to use guerrilla tactics” gained support, the government offered the sop of the Local Defence Volunteers. It was soon clear that this was a half-hearted attempt, reflecting the establishment’s fear of ‘arming the workers’: the LDV were to be no more than ‘Special Constables’ whose role was to patrol and report. Guns volunteered by local communities were immediately locked up in the local police station.

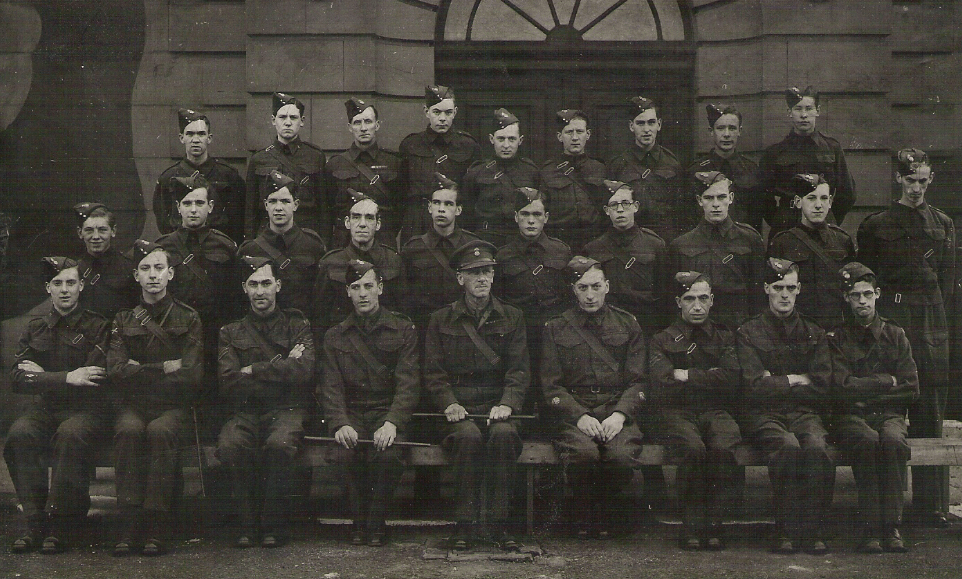

Wintringham would have nothing of it. With support from the Picture Post, he opened up a military training camp at Osterley Park to show the LDV what a guerrilla army should look like. Bringing over Basque miners, expert in destroying German tanks, and other International Brigade veterans, within a few weeks 5,000 LDV volunteers had passed through his capable hands, as well as a Guards regiments from the regular Army.

Michael Foot backed Wintringham

The attitude of the LDV volunteers who flocked to Osterley Park was summed up by Norman McKensie, an ILP member: “If the government had made peace that Summer, we would have rebelled; abortive no doubt, but we would have tried. We saw ourselves as the heirs of Spain. We wanted a socialist government, and we were going to fight fascism at home, if needs be, as well as the Nazis.”

Backing Wintringham, Michael Foot, the future leader of the Labour Party, but then writing the popular Casandra columns in the Daily Mirror, said the current war was a continuation of the fight against fascism in Spain.

Wintringham even attempted to address the chronic shortage of weapons for the LDV by launching in the USA – with the help of Kitty Bowler – the ‘Committee for American Aid for the Defence of British Homes’. The US public donated 10,000 weapons, albeit a motley collection, ranging from long barrel rifles from the 1870s, through to Tommy guns donated by sympathetic gangsters (who despised Mussolini for his pledges to dismantle the Mafia in Sicily).

Formation of the Home Guard

Wintringham got his way – the defeatists in the government were swept aside, after the Labour Party said it would only enter a ‘national’ government if it was led by a Tory who wanted to fight, and Churchill was the only Tory leader who could be trusted to do that.

Later, the half-hearted LDV was transformed into the more militarised Home Guard, and Osterley Park was brought into the official training programme. Throughout this period, the CP viciously sniped at Wintringham, accusing him of “deceitful propaganda”, but no one in the labour movement was listening to them: the Hitler-Stalin Pact and the carve up of Poland left the British CP twisting in the wind, as once again they slavishly followed the party line.

The political cowardice of the CP in 1940 was a tragedy, given the revolutionary opportunities of that time. Britain in 1940 was not a united island of Churchill and Spitfires as a generation of capitalist historians would later have us believe. Rather, as Purcell writes, it was “a land of seething anger” at the old order that had brought Britain to the brink of defeat. But there was no revolutionary party to take the lead. As George Orwell lamented in his diary a year later in 1941: “Last summer a revolutionary situation existed in England, though there was no-one to take advantage of it.”

The Common Wealth Party

As the threat of invasion subsided, so Wintringham fell into the background. His next major venture was to put his beloved Popular Front into political form, with the launch of the Common Wealth party. He shared the CP’s belief in 1945 that the labour movement was not yet capable of winning power independently, so alliances should be built with ‘progressive elements’ amongst the middle classes.

The Common Wealth Party demonstrated the ideological poverty of popular frontism, of accepting the ‘lowest common denominator’ of policies, to appease his new allies in the ‘progressive movements’. There were a few electoral successes in the shape of wartime by-election victories, gaining from the opposition to the government where the main parties had an agreement not to contest each other’s seats. But that temporary success was buried by the Labour landslide of 1945, as it swept to power on its most radical programme ever.

Marxism distorted by Stalinist ideas

The Common Wealth Party, meanwhile split between those who wanted a ‘moral revolution’ and those around Wintringham who wanted a social one, and Wintringham died soon afterwards. He was at heart a liberal, whose grasp of Marxism had been sadly distorted by his Stalinist ‘teachers’.

But that aside, he was the forceful individual who brought us the International Brigade, public air raid shelters and the Home Guard, and for that alone he should be commemorated. A statue, perhaps?

The Last English Revolutionary, Tom Wintringham 1898 – 1949, by Hugh Purcell, was published by Sutton Publishing Ltd and copies can still be found on the internet.

Fenner Brockway picture