By Caroline Forde and Nata Duvvury, in Galway

As we celebrate the advances made in gaining women’s economic rights, there is the continued presence of coercive control that restricts women from reaching their potential. Coercive control has recently entered the Irish collective consciousness, as we begin to thoroughly grapple with the profound complexities of domestic violence.

The international news has also been dominated, of late, by story after story from survivors of coercive control, such as Evan Rachel Wood and FKA Twigs, described in the Irish Times A common thread involves the manipulation that causes survivors to question their experiences and feelings, a tactic perpetrators employ to transfer the blame to their victims.

Pervasive abuse

Coercive control was recognised as a serious criminal offence in the Irish Domestic Violence Act 2018, heralding a long-awaited era where the pervasive abuse largely taking place behind closed doors could finally be addressed within the criminal justice system. Since then, there have been two convictions under this legislation.

The need for Ireland’s coercive control legislation was two-fold. Firstly, to provide a legal definition of domestic violence and, secondly, to encompass the complex dynamics involved. A salient part of the latter relates to the common myth that domestic violence is physical alone.

Recognising that domestic violence involves a pattern of coercive control perpetrated in intimate relationships broadens our knowledge of this pernicious crime, enabling us to better understand the trauma survivors endure, as well as the entrapment that makes it so difficult to escape an abusive relationship and lead lives full of productive potential.

Monopolisation of vital resources

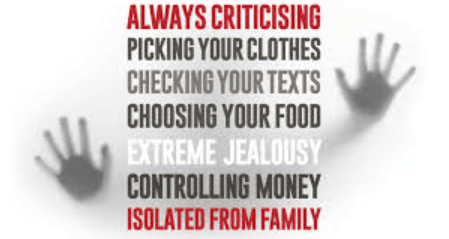

Perpetrators of coercive control employ several tactics, such as structural forms of deprivation, exploitation, monopolisation of vital resources and threats. Verbal, physical and sexual violence are interwoven with intimidation, isolation and control. However, the focus is on control and dependence, primarily brought about by perpetrator-enforced regulatory regimes. So, why is this important?

Recognition of the insidious dynamics of domestic violence means that barring orders and criminal convictions need not rest on physical evidence of abuse. Psychological, emotional and financial control have finally been criminalised as serious offences that inflict profound harm.

That is the promise of the coercive control legislation. Manipulation and degradation would no longer be minimised or denied. The signs would become clear, and we would understand the diverse impacts for women, children, family units, communities and the economy.

As such, we welcome the recent coercive control convictions and stand in solidarity with the women who pursued criminal charges. But how can we wholeheartedly commend these convictions, while at the same time turning a blind eye to the institutional abuse that is currently being denied?

Mother and Baby institutions

In their searing piece published in Left Horizons on February 22nd, Saoirse Nic Gabhainn and Lorraine Grimes trace our longstanding history of institutional coercive control, from Mother and Baby institutions to Direct Provision. They also highlight the many problems with the recently published Commission’s report concerning the Mother and Baby Institutions, such as the fact that its conclusions do not reflect the lived experiences of survivors.

As voiced by many women, their testimonies have been ‘twisted’. Thus, we not only have a denial of past coercive control but also current controlling tactics to support this atrocity. In denying the coercive confinement of these women, the Commission and State are gas-lighting them – questioning their memories, blurring their realities.

In addition, recordings of the oral testimonies provided were destroyed without consent, while survivors were again presented with a rewrite of history (they were not told the recordings would be destroyed, as validated by their consent forms). Thankfully, these recordings can be retrieved.

Blamed shifted to society and individuals

Much has also been said of the report’s downplaying of the Church/State nexus role in the institutional abuse, with the blame predominantly shifted to ‘society’ and individuals. Does this sound familiar? If so, it is because it is another element of coercive control – accepting some responsibility for one’s actions, while fudging overall responsibility.

The suggestion is that the sexual mores of the time were designed by the individual people of Irish society or that these mores materialised out of thin air. As such, adherence to norms has been conflated with the establishment of norms, and the role of authority figures.

The report’s ambiguity regarding responsibility is nowhere more evident than in statements such as the following:

‘Women who gave birth outside marriage were subject to particularly harsh treatment…However, it must be acknowledged that the institutions under investigation provided a refuge’.

Orwellian doublethink

This example highlights the Orwellian doublethink we are expected to engage in. To name these carceral institutions as a ‘refuge’ is reprehensible. It not only does a severe injustice to the institutions’ survivors, but also to survivors of domestic violence and the organisations providing them a safe place.

This ongoing mishandling of the Mother and Baby Institutional abuse amidst the societal awakening to the nature of coercive control gives one pause.

We must be able to feel confident that coercive control will never again be misunderstood or minimised. Which brings us back to domestic violence. Looking more closely at the recent convictions, one involving repeated phone calls (Donegal) and the other severe physical violence (Dublin), we question whether future cases will require such evidence to be seen as legitimate.

Subtle signs of coercive control

Would the twelve-year sentence (with two suspended) have been handed down in the Dublin case if no physical violence were involved? Would the seriousness of the coercive control have been recognised if the repeated physical attacks were not dominating the reporting of the crime?

This case highlights how abuse can continue when it is undetected despite numerous opportunities [the woman accessed healthcare 19 times before Gardaí (Irish police) were contacted]. Given the often more subtle signs of coercive control, we must have a concrete understanding of what such abuse entails.

We argue that this can only fully happen when complete and unambiguous responsibility is taken for the Mother and Baby institutions and when we close DP centres. This is a history we must never forget, a history we must fight to make all possible recompense for. This is our present. To fully ensure the meaningful application of our coercive control legislation, all forms of coercive control must be acknowledged. We must urgently build upon the good work that has begun.