Trump’s tariffs – some facts and consequences (from various sources)

Trump’s tariffs – some facts and consequences (from various sources)By Michael Roberts

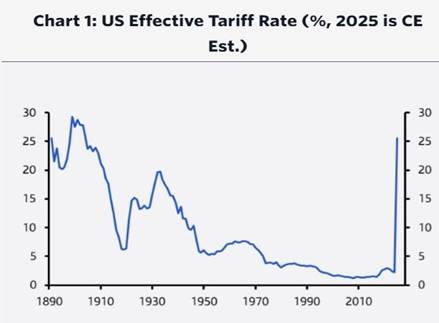

1. The overall impact of Trump’s tariff hikes is to raise the average tariff rate on US goods imports to 26%, the highest level in 130 years.

2. The formula used to establish the tariff for each country exporting to the US is not related to any unfair taxes, subsidies or non-tariff barriers imposed by countries on US exports. Instead, it follows a simple formula: namely, the size of the US trade deficit with each country divided by the size of US imports from that country, then divided by two. An example: America runs a US$123bn deficit with Vietnam from which it imports US$137bn. So it is deemed to have trade barriers equating to a 90% import tariff. The US formula applies a reciprocal tariff of half that (45%), to reduce the bilateral deficit by half. Problem: Vietnam does not have a 90% tariff on US exports, so it cannot avoid a reduction in sales to the US by agreeing to reduce its ‘tariffs’ on US exports.

3. The moves will have a significant impact across the countries of the Global South. Some of the highest tariff rates are among lower-income developing countries in South and Southeast Asia like Cambodia or Sri Lanka.

4. Trump’s tariffs are only on goods imports, not services. The US runs a deficit on goods with the European Union countries, so Trump has imposed a 20% tariff on those imports. But there are no measures against services (about 20% of all world trade). The EU runs surplus on goods with the US, but a significant deficit in services (banking, insurance, professional services, software, digital communications etc) with the US. If services had been included, the US deficit with the EU would virtually disappear.

5. All countries, even those running a deficit with the US in traded goods, are subject to a 10% tariff. This also applies to countries without any trade with the US or any people (Diego Garcia, Antarctic…). The tariff on the UK is 10%, for example. So, although the UK goods trade is virtually in balance with the US ($58bn to $56bn), it will still take a hit from a loss of goods exports to its largest trading partner, the US. If Trump’s tariff formula for goods were applied to the UK, then there should be no tariff on imports from the UK. In contrast, if services trade were included, the tariff on imports from the UK would be 20%! Morgan Stanley reckons the new tariff regime could knock up to 0.6 percentage points off UK growth (which is virtually zero anyway).

6. Tariffs will substantially increase prices—US consumers will bear the brunt on a wide variety of basic foods and essential goods that physically cannot be produced domestically, with the poorest households being hit the hardest. American industry will struggle with higher costs for key intermediate supplies, machinery, and equipment, dwarfing any marginal benefits from reduced foreign competition.

7. Another example: the 54% tariff on China could result in a drop of $507 billion in imports – and China only exports $510bn in the first place. Trump’s China tariffs would reduce American imports by roughly 20%. This would cause a ‘supply shock’ similar to the pandemic period, leading to a US recession and/or inflation.

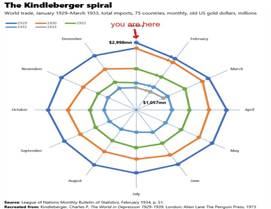

8. Retaliation by other countries will lead to a fall in US exports. In the 1930s, after the Smoot-Hawley tariffs were imposed, retaliation led to a 33% fall in US exports and spiralling down of international trade called the “Kindleberger Spiral”: a cycle where tariffs reduce trade, then retaliation reduces it further, then more retaliation, then first order effects on output, then second order effects, then more tariffs and retaliation, until global trade fell from $3 billion in January 1929 to $1 billion in March 1933.

9. A tariff trade war would hit the US economy harder than Smoot-Hawley, since trade is now three times as big a share of GDP as it was in 1929, and was 15% of GDP in 2024 versus roughly 6% in 1929.

10. US real GDP this year could be down by 1.5-2 percentage points and inflation could rise to close to 5% if these tariffs are not reversed soon (UBS forecast).

11. Falling trade growth from tariffs will lead to falling international capital flows, weakening investment and economic growth globally.

From the blog of Michael Roberts. The original, with all charts and hyperlinks, can be found here.

G20 muddling through… …at the expense of the world’s poor - By Michael Roberts This weekend, the G20 leaders’ summit takes place – not physically of course, but by video link. Proudly hosted by Saudi Arabia, that bastion

G20 muddling through… …at the expense of the world’s poor - By Michael Roberts This weekend, the G20 leaders’ summit takes place – not physically of course, but by video link. Proudly hosted by Saudi Arabia, that bastion Labour’s crisis of free speech - By John Pickard According to an article in the Jewish Chronicle, (November 16), newly-elected Labour NEC member, Gemma Bolton, is under ‘investigation’ for a two-year old

Labour’s crisis of free speech - By John Pickard According to an article in the Jewish Chronicle, (November 16), newly-elected Labour NEC member, Gemma Bolton, is under ‘investigation’ for a two-year old Class battles will happen under Biden - By Richard Mellor in California The US election and defeat of Donald Trump brought a collective sigh of relief to millions of people throughout the

Class battles will happen under Biden - By Richard Mellor in California The US election and defeat of Donald Trump brought a collective sigh of relief to millions of people throughout the Covid 2021: more calamity ahead? - By Michael Roberts The news that a COVID-19 vaccine could well be available by the start of 2021 sent the stock markets of the world

Covid 2021: more calamity ahead? - By Michael Roberts The news that a COVID-19 vaccine could well be available by the start of 2021 sent the stock markets of the world Boris Pilnyak: The Unextinguished Moon - By Andy Ford, Warrington South CLP October 30th was the anniversary of the death of the Red Army leader, Mikhail Frunze, in 1925, likely as a

Boris Pilnyak: The Unextinguished Moon - By Andy Ford, Warrington South CLP October 30th was the anniversary of the death of the Red Army leader, Mikhail Frunze, in 1925, likely as a